Carol Oates takes the title of her twentieth-and perhaps most assured and impressive-novel from Stephen Crane's poetry sequence, "The Black Riders and Other Lines," wherein the narrator comes upon a creature in the desert who is consuming his own heart and likes it not because it is "good," but precisely for its bitterness, and because it is his alone. There are many justifiably embittered hearts among Oates's characters, and if the morally most aware among them hang on tenaciously to their bitterness, it is not from some senseless clinging to their own misery, but from a desire to remain in touch with feelings and passions that others either cannot comprehend or refuse to countenance.

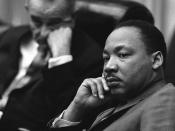

Urban upstate New York from the mid-1950's through the early 1960's-the years of the Civil Rights movement, the ascendency of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy-as Oates depicts it in Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart is a place where distinctions and exclusions based on class and gender and especially on race are rigidly enforced.

Oates's novel is filled with incidents of racial prejudice, some only reported, many brutal and violent:Blacks relegated to the backs of buses; the courts depriving a woman of her children when she marries a mulatto; a bigoted mayor preaching the supremacy of whites as the foundation of the republic; white police murdering or intimidating blacks, and white military officers physically disabling black inductees; white doctors providing inadequate care to blacks; teachers seating schoolchildren by race, or covering over hatred for all blacks by selective preference for some few.

Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart is a novel of crime and expiation, almost Dostoevskian in its reach. It opens strikingly, with the discovery of the body of Little Red Garlock, killed the night before in a fight with Jinx Fairchild. From a poor family-even the blacks regard them as "white trash"-Little Red, himself physically abused by his drunken father, is a spiteful and dirty-mouthed bully who glories in the humiliation of others. One of the victims whom he chooses to torment is fourteen-year-old Iris Courtney, first taunting her, then throwing gravel at her face, and finally insinuating a sexual relationship between her and Jinx, a black high school basketball star. Jinx, who responds instinctively and almost unaccountably to Little Red's treatment of Iris, kills him, taking another life to protect a white girl he barely knows. How Jinx and Iris live with the dark secret that they share-justifiably fearful that no one would believe the truth of their Story even if it were told-and also with their muddled and ambiguous feelings about each other, becomes the center of Oates's absorbing story.

Jinx, a good student and standout athlete, is, indeed, the fair child of his family (his only brother, "Sugar Baby," will die ignominiously late in the book, brutalized by henchmen for a disgruntled drug dealer). His father, Woodrow, disabled in a racial incident while in the armed services, more recently could not break out of his "paralyzing shyness" to speak up and defend himself when unjustly suspected of sexual molestation. So it remains for Minnie, Jinx's mother, to keep the working- class family going financially. Not one to tolerate "crybabying" about the color of one's skin, she believes that Dr. King's well-intentioned efforts have only worsened tensions. After the white doctor for whom she has worked dies, though, and she becomes a domestic for employers who cannot see beyond the color of her skin, she begins to experience the hopelessness of insulating her family from racial prejudice merely by trying to act as little different from whites as possible.

To Minnie's way of thinking, even her prized son's nickname is too "black," yet his other nickname, "Iceman," might seem even more unenviable, prescient as it is of the moment when his murdering hands seemed to be acting independently of himself, altering his future. A believer in "conscience" if not in any clearly defined God, Jinx waits-despite Iris' insistence that he had no choice and that she is the responsible one-for his punishment. Iris correctly perceives that he at least unconsciously inflicts that punishment on himself when, in the state championship game, he brings his dream of a career in basketball to an abrupt end when he comes down wrong and shatters an ankle.

Yet Jinx justifiably ponders whether, even if he were to fulfill his dream of athletic success, it would not be just another form of enslavement to the white majority. Would not a basketball scholarship offer merely one more road to degrading himself as a "performing monkey" and becoming like a white boy? Without basketball, he would be just another "nigger boy" in white eyes. When Iris' uncle Leslie gives him a photograph he will come to treasure of black soldiers in the Union Army, Jinx is taken with their evident "composure" in the face of death; at the same time, nevertheless, it causes him to reflect on the way that soldiers throughout the history of the United States have been "exploited by the Man." In spite of this-and perhaps as a continued expiation-Jinx, locked into a marriage that deteriorates into an increasingly abusive relationship, enlists to go off and fight in Vietnam: Uncle Sam pointing a finger and wanting him for something is better than being nothing. Sports and war, the pattern of Jinx Fairchild's life clearly indicates, remain the only two avenues of possibility for black men who do not choose a life of crime.

A long while after the death of Little Red, Jinx and Iris have a meeting in which he comforts her physically (but without the sexual consummation he knows is neither possible nor desirable); Iris, however, will continue to believe that no other couple could ever be as "close" to each other as they are, and that he will always be the "only real thing in her life." Even when she finally becomes engaged, her fiance's presence only confirms Jinx's "absence." Much, in fact, of what Iris does in the years following Garlock's death is motivated by the need not to let go of the secret knowledge she and Jinx share between them, for it helps counter her vague sense of insubstantiality, of "not-thereness." The daughter of a fun- loving couple-by avocation ballroom dancers in the style of Vernon and Irene Castle-desperately in need of "good times" and increasingly beleaguered as the story proceeds, Iris even muses that if she were "colored" instead of white, she might have a firmer sense of her own identity. She worries as well about an inherited propensity toward being cynically cold-hearted and mean-spirited. And so she immerses herself in books, which afford "competing versions" of reality and help release her from the here-and-now.

Whereas Jinx finds it necessary to punish himself when no silent and unresponsive God (if he even exists) does, Iris handles her unfulfilled sense of responsibility by a kind of compulsive, if unconscious, repetition of the triangular tension that led to Garlock's death in the first place, as if to provide sufficient reason years afterward for Jinx's action-very nearly a ritual sacrifice to make his earlier one meaningful. Confronted in a college boardinghouse by a Caribbean graduate student who tries to assault her, she pulls a knife on him to avenge Jinx's honor and manhood. Later; on the night of Kennedy's assassination, after leaving a black cafe where as a white she felt invisible, Iris is dragged into a car by a group of black males, taunted with racial slurs, and sexually abused; in a sense, what Little Red had accused her of, and the violation Jinx killed to preserve her from, has come to pass.

In order to marry the art historian Alan Savage, Iris must bury her real self; except for Alan's profession of "forgiveness" for what the young blacks did to her; what she holds within her heart can never be broached between them. Indeed, she must largely refashion her past through lying so as to be socially acceptable to the upper-class Savages, whose house is like that of a dream castle from a movie and who virtually adopt Iris for their own even before she becomes engaged to their son. The elder Savages would appear to be ironically named, for they are a bastion of "civilization." There is a certain smugness about them: They find it easy to believe in God, since God has been good to them; and they can afford to be magnanimous, since they remain insulated from events and people in the world around them that they would much prefer not to know intimately. The novel's close, the last-minute preparations for Iris' marriage to Alan, might appear overly sentimental and melodramatic, and indeed throughout its history domestic melodrama has often centered on how those who are powerless and apparently nonproductive in the larger society can negotiate some recognition and place for themselves within the family unit; the happy ending that arises, if not unexpectedly then at least somewhat improbably, can comfort those who feel they have little control over their lives. Yet the romance of the novel's conclusion is undercut by Iris' vision of herself in the mirror, where she sees only the "luminous" white wedding dress for her marriage to a white man-the only socially acceptable ending in a racially intolerant society. Even Jinx knew that her fate was to be "a little white doll baby." In Iris' mind, though, whiteness has somehow always had something to do with guilt.

Among the several patterns of imagery that contribute to the texture of Oates's novel, two others, besides the black/white dichotomy, are particularly resonant: those of blood, and those related to photography. As a young girl, Iris wonders if the blood of blacks is somehow darker than that of whites, or if there is such a thing as black blood that makes them different-only to find that black Lucille's blood is as red as her own swimming suit. Iris' father Duke buys into a racehorse, talking about bloodlines and pedigrees and purity as opposed to mongrelization-akin to the racially mixed companions that he warns Iris against. Further, there is the blood of sexual arousal, of the physically brutal lovemaking of Jinx and his wife, and of Persia Courtney's fatal illness.

Of all the characters in the book, the person most enlightened about, and therefore able to be effortlessly nonchalant about, mixing of the races is Leslie Courtney, Duke's brother, who is secretly but chastely in love with Persia. Photographic negatives, in which white is black and black white, erase completely the traditional notions of difference based on surface coloration. Leslie still feels guilty over the abominable fact of slavery; and Duke is openly worried that his brother risks becoming known as "the Negro photographer." For Leslie, to be without his camera would be tantamount to being blind, lacking the vision necessary to seizing beauty: The camera, an instrument for perceiving God in worldly phenomena, is his eyes-and Iris, her mother tells her, was named not for the flower, as might be assumed, but for the eye. Yet Leslie claims to be dispassionate when behind the camera, so that there is an absence of himself from the resulting photographs, in a way that Iris never can be from what she sees. If photos for her are a further proof of existence, of being really here, they simultaneously denote change and death, both possibility and demise. Back in the 1940's, Leslie created a massive photographic collage (a structural pattern Oates's novel shares as well) composed of hundreds of faces of children of different races, "a cascade of humanity" that fascinates Iris and, years later; Jinx when they visit his studio. The collage's title, "'And the Light Shineth in the Darkness, and the Darkness Comprehended It Not,'" can serve, finally, as a gloss reflecting the awful fact of racial prejudice and bigotry that integration seems powerless to break through. Iris and Jinx must hold the revealing bitterness of their experience in their heart, for it is too terrible, yet potentially transformative, for the world to accept yet.

Two comments in the novel about the nature of art and its impact upon humankind-that it is "surfaces by way of which, and by way of which exclusively, the interior world-soul shines," and that "the code of the work doesn't matter anyway, the 'meaning' doesn't matter, it's the fact of the work, whether, seeing it, you are stopped dead in your tracks"-are especially pertinent to Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart. Oates here tells a mesmerizing tale, full of trenchant social observation and with an astonishing control of a variety of voices. More so than any other of Oates's long fictions, this novel has the look and feel of permanence about it. It seems, along with the fiction of Toni Morrison, a major contribution to the literature about how love operates-or fails to operate-amid racial tensions in America.

referencesCreighton, Joanne V. Joyce Carol Oates: Novels of the Middle Years. New York: Twayne, 1992. A discussion of fifteen Oates novels written between 1977 and 1990. Of American Appetites (1989) and Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart, Creighton comments, "The American dream is fractured by an unintentional killing; in both, violence is an upwelling of tension, breaking through the civil games of society and the conscious control of character; in both, appetite s remain unfulfilled."Gates, Henry Louis. "Murder, She Wrote." The Nation 251 (July 2, 1990): 27. While he singles out Oates's rendering of racial resentment, Gates maintains that "the real spine of the book may be in its brilliant dep iction of downward mobility, the painful fragility of the Courtneys' standing in the world."Johnson, Greg. Invisible Writer: A Biography of Joyce Carol Oates. New York: Dutton, 1998. Furnishing a candid portrait of Oates, Johnson explores Oates's private and public life. He pays considerable attention to her later, largel y ignored novels, and suggests that future critics will be more appreciative of hennr insightful commentary on American life.

Johnson, Greg. Understanding Joyce Carol Oates. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1987. Johnson sees Oates as a writer with a broad and sweeping vision of contemporary America. Discusses her deployment of gothic strategies an d her ability to explore intense psychological states.