That morning, the sound waves of piston engines bouncing off Hawaiian valleys radiated for miles. The sound, familiar to most that lived at US naval station Pearl Harbor, caused little disturbance or commotion. It has been documented that most of the inhabitants believed the noise to be of American aircraft on a practice flight. But, the noise was not that of an Allison power plant or even that of a Rolls Royce V-12. All that was heard was the familiar resonance of friendly aircraft, until the first bomb exploded, and the first American serviceman was killed. With that singular first bomb, Japan awoke a ?sleeping dragon,? as said by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who had previously studied and lived in the US. He attended the Naval War College and had studied at Harvard University, and he was no stranger to American combat tactics. (Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Japanese Navy, 1884-1943) Yamamoto was correct in is statement; and the US would ?awaken? to combat the forces of Japanese Imperialism to the death.

However the US would struggle to achieve much success against the Japanese war machine until April 18, 1942. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) Exactly one hundred and thirty-three days after the dastardly attack on Pearl Harbor, Tokyo staged an air raid drill that Saturday morning, but it ?bore little realism. No sirens sounded. Air raid wardens gazed at a placid sky? At about noon the drill came to an uneventful end. Because no sirens had announced its beginning, none signaled its conclusion. War workers laid down their tools and began their midday break. Millions of other Tokyo residents went shopping, visited parks and shrines, attended festivals, and watched baseball games.?(Legendary Jimmy Doolittle) Not one single Japanese citizen anticipated an American attack, and not one person, military or civilian, were prepared for it. However the days following events would be dubbed ?the ??Tokyo Raids?? or the ??Doolittle Raid???after its legendary leader, Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle. A startling attack by American bombers that seemed to appear out of nowhere?only to vanish as suddenly as they had appeared. An assault on Japanese pride that left a firebrand mark. A feat of flying that seemed impossible?yet one that with dash and daring actually had been achieved.?(Legendary Jimmy Doolittle) Although the Doolittle Raid was only a limited military action, it changed the entire course of the war in Pacific, and led Lt. Col. Doolittle to fame as one of America?s premiere leaders.

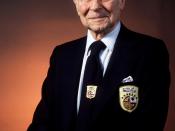

General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle was born on December 14, 1896, in Alameda, California. Gen. Doolittle lived and grew up in Alameda and also in Nome, Alaska. Around the time of October 1917, Doolittle enlisted in the United States army Reserve. He was almost immediately assigned to the Signal Corps, and he also served time as a flying instructor during World War I. In the month of July, in 1920, Doolittle was commissioned as first lieutenant in the air service, regular army. Doolittle served in reserves and during his free time he flew airplanes for pleasure. On September 24, 1922, he made the first transcontinental flight in less than 24 hours. In 1923, Doolittle was sent to MIT, by the army, for advanced engine studies. During his stay at MIT, and along with his studies on advanced engine theory, he also spent five years learning about diverse engineering studies. In September of 1929, Doolittle made the first successful test of a blind, instrument-controlled landing. Doolittle was also an accomplished air racer. After leaving the army in 1929, he primarily raced the short, awkward looking plane dubbed the ?Gee-Bee.? With this aircraft, he won the Harmon trophy and he set the world speed record in 1932. While he was away from the army, he also served on various government and military consultative boards. Shortly before the US entry in to World War II, Doolittle returned to active duty as a Major in the army air corps. (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) After 7 December, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wanted his Chiefs of Staff to find some way to attack the very heart of Japan. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) Aaron G. Carter first thought up the original plan, being very primitive and unrefined. (Glines, Col. Carroll Glines V.) Carter was a close friend of Maj. General Edwin ?Pa? Watson, and Gen. Watson forwarded Carter?s letter to General ?Hap? Arnold. About the same time, Capt. Francis S. Low, a submarine officer and graduate of the United States Naval Academy, presented plans to his boss, Chief of Staff Admiral Ernest King. In Low?s original plan, he proposed to the Navy?s newest aircraft carrier, the USS Hornet, to carry out a potential strike on Japan. This proposal occurred on January 10, 1942. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) Low also suggested also the use of the army?s medium range, twin engine bomber, the North American B-25, because of their medium size. Upon hearing Low?s proposal, Admiral King instructed Low to contact his friend Captain Donald B. Duncan. Duncan would handle further planning and logistic work. After receiving the call from his trusted friend, Duncan locked himself in a vacant office building and started his work on one of the most top-secret military projects of our time.

In order to construct accurate plans, Duncan consulted various sources including: historical records of heavily armed planes taking off in short distances and weather patterns for determining the best time for a raid on the Japanese islands. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) At the conclusion of five straight days, Duncan eventually emerged from his office, with him, a thirty-page analysis. This analysis was all hand-written for reasons of security. ?The script, envisioning a dramatic surprise attack on Japan?s major cities by US Army bombers launched from an aircraft carrier, projected the very sort of dramatic retribution that Roosevelt?and America?so intensely desired.?(General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Duncan eventually settled on the North American B-25 bomber because it could carry 2,000 pounds of ordinance and could complete a 2,000-mile journey, provided it were properly modified. The USS Hornet would be used because of its speed and large deck space. The Hornet would take the 16 B-25s and their crews, at twenty-five knots, directly into harm?s way. Low and Duncan agreed that the Hornet would need an entire other task force to accompany her on her way to the Japanese islands for safety reasons. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) The task force chosen to set out ahead of the Hornet, was Task Force 16, led by the legendary Admiral William ?Bull? Halsey. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) ?It would take a phalanx of US Navy warships?Task Force 16?to get the Doolittle Raiders within striking distance of Japan.?(General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Duncan and Admiral King thought the task force should bring the carrier within five hundred miles of the Japanese coastline before the planes were launched. After the bombers struck their individual targets, the task force would turn around and head for more friendly waters. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) Duncan concluded that Army Air Corps pilots would need to be trained on how to take-off from a pitching, mobile airstrip. Duncan and Low had the exact dimensions of a carrier deck painted on a runway at the naval base at Norfolk, Virginia. (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) This mock-carrier deck would be used to simulate taking off from the carrier?s deck with full ammunition and fuel load.

After the initial plans had been created, they were shown to Admiral King for his approval. King indeed approved of the plans and gave Duncan and Low the go-ahead to start training and preparation. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) After hearing his men?s proposal, King immediately called General ?Hap? Arnold to try and find a man to lead the attacks. General Arnold personally selected Lt. Colonel ?Jimmy? Doolittle to oversee the mission. Arnold knew ?if it had wings and looked like a plane, chances are good that Jimmy Doolittle either had flown it or could fly it.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Arnold called him at his home to notify him of his wishes on December 24, 1942. Doolittle arrived eight hours later on December 25, 1942. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) ?Doolittle accepted the challenge without hesitation. Arnold made it clear, however, that it was Doolittle the planner he wanted for the job, not Doolittle the pilot?Despite Arnold?s wishes to the contrary, Doolittle deliberately wrote himself into the scripts as pathfinder. He would pilot the first B-25 off the carrier. His plane would illuminate Tokyo with incendiaries as a beacon for the fliers following him.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) The plan was to take off from the Hornet; bomb selected targets in Tokyo, and land in China. ?Because carrier landings were impossible for the ten-ton aircraft, this would be a one-way mission. Instead of returning to their launch point after the raid, the planes would continue west to the Asian mainland, arriving at fields in China or the Soviet Union. Doolittle estimated the chances for success at fifty-fifty.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) In order to get clearance to land in China, President Roosevelt started diplomatic talks with Generalissimo Chaing Kai-shek. ?Arnold and Marshall asked-forcefully-that he permit American raiders to land in eastern China.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Along with Kai-shek, the Chinese ambassador agreed on terms to establish American-based air-superiority. After finalizing plans with China, on January 28, 1942, General Arnold, Admiral King and General Marshall met with President Roosevelt to inform the Commander in Chief of their progress. Roosevelt was pleased with their findings and gave his authorization to start training at once. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) On 31 January 1942, Duncan reported to Norfolk, Virginia, to begin training the crews that would partake in a truly historical event. Another aircraft expert was called in to modify and test the B-25, Lt. John Fitzgerald. Lt. Fitzgerald had logged well over four hundred hours in the twin-engine bomber prior to the war. If there was any man who knew more than Lt. Col. Doolittle, it was Fitzgerald. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) On 1 February, Duncan first informed the skipper of the Hornet, Captain Marc A. Mitscher, of his orders to let the members of the training crew use his ship for experimental purposes. At Norfolk, and throughout February and into March, ??the B-25 pilots practiced short-field takeoffs. Coached by Lieutenant henry Miller, a Navy flight instructor, the Army men learned to hang on their props, fighter style. Flags every fifty feet along the runway?s edge helped them gauge the minimum distance required to get their planes airborne. ??We practiced over and over, ramming the engines at full power, ??says copilot Jack Sims, ??taking off at sixty-five miles per hour in a five hundred foot run. It could be done, as long as an engine didn?t skip a beat.??? Doolittle as well, trained in the short take-off runs. (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) The planes had to have many intricate modifications done to them; and their engineers had to be briefed on how to maintain their aircraft should the need arise. The aspect of fuel and armament weight was a major problem that faced the mission planners. ?To extend the B-25?s range, technicians installed to hundred and twenty five gallon auxiliary fuel tanks in the planes? bomb bays and replaced the bottom turret mechanism with a sixty gallon tank.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) The top secret Norden bombsight was replaced, due to security reasons, with a ?two-piece gadget?at a cost of twenty cents?in its place.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Also the aft machine guns were replaced with two thick broomsticks, mounted to the turret. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) After four long weeks of training Doolittle felt his men were ready for the task at hand. In late March, the bombers were flown to the training site, Englin air force base, to McCellan field, near Sacramento. After an intense final shakedown, the sixteen planes were loaded on the Hornet, stationed at Naval Air station Alameda. From there the task force, and its precious cargo, set sail for Japan. ?On the afternoon of April 2, with the dark-green bombers lashed to its flight deck, the aircraft carrier, escorted by two cruisers, four destroyers, and an oiler, sailed into the Pacific.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) En route to Tokyo, Doolittle informed his men about the mission details. He explained where, when and with what, they would be attacking Japan. ?Doolittle allowed each crew to pick its targets. Some wanted to bomb the Imperial Palace. He forbade this, not out of respect for Emperor Hirohito, but because such an assault would only inflame Japan?s fighting spirit.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Some crew members were skeptical about the mission. ?One night, Corporal Jacob DeShazer, bombardier for Plane No.16, ??Bat Out of Hell.?? Stood alone on the flight deck. ??I began to wonder how many more days I was to spend in this world,?? he recalled.? (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) During the days of April 16 and 17, the ordinance men and the flight crews checked and re-checked all aspects of the mission. The bomber?s tanks were filled to the brim with the life-giving gasoline. Bombs that would rain a fiery hell upon Japan were loaded into the B-25?s bomb bays. (Glines, Col. Carroll V.) At three a.m. on April 18, the Enterprise?s radar picked up two small ships about eleven miles out. The ?General quarters? call was given, waking the sleeping Raiders from their slumber. The task force veered to the right to avoid contact. The ships continued on towards the enemy coastline until about 7:30 a.m. ?Lookouts aboard the Hornet spotted an enemy patrol boat. The tiny craft was just visible in the mist, about ten miles away. The task force had just encountered Japanese Patrol boat Nitto Maru?Dive-bombers from the Enterprise joined in the attempt to sink the Japanese vessel, and finally, at 8:23 a.m., the Nitto went down.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) The Hornet was about seven hundred miles from the Japanese coastline, and at 8 a.m., Halsey flashed the ?go? signal to the Hornet. ?Army pilots man your planes!? At 8:15 Doolittle revved the engines of his B-25 and lurched forward. With green ocean water spilling over the flight deck, Doolittle and his crew leapt off the deck with ?yards to spare?(Lawson, Capt. Ted W.) The rest of the Raiders soon followed suit. All of the planes left the Hornet by 9:15 a.m. En route to Tokyo, the planes flew at forty feet and one hundred and fifty miles per hour. The Raiders would reach land by midday.

?The planes were to go in as lone raiders. Three of those following Doolittle would hit the northern sector of Tokyo, three the central sector, and three the southern sector. Three other would strike Kanagawa, Yokohama, and the Yokosuka Navy Yard. The last three bombers would hit targets in Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Shortly after noon, the Raider raced over the coastline hilltops of Tokyo. Their targets lay five minutes farther inland. As soon as he approached his target, Doolittle lined up his bombsight and at ?12:15 p.m., a red light blinked in rapid succession on Doolittle?s instrument panel. Four incendiary clusters rained down on Tokyo.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) As soon as the Japanese realized what was occurring, they started to fight back; however to no avail. ?The Raiders skimmed over treetops and hillocks. Pilots gunned their planes up to a thousand feet above the sprawling city. Bombardiers brought their sight to bear on their targets. Then came the blink, blink, blink as four five hundred pound bombs plummeted from each bomber.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) It was all over in thirty seconds. In the days following the raids, Japanese officials reported 90 casualties and 200 injured.(Lawson, Capt. Ted W.) After the bombings, the crews pushed east towards China. After thirteen hours of flying, the night consumed the evening air. All of the planes fuel gauges read ?zero.? Most pilots figured that they would keep flying until they ran out of gas and then would jump out. Eleven out of sixteen crews did in fact bail out, including Doolittle. Doolittle was one of the lucky ones, he and his crew landed in a rice paddy, some three hundred mile into China. Plane No. 2 attempted a crash landing, as well as planes 7 and 15. Planes 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16 all bailed out. Plane No.6 bailed out over the Chinese coast and its crew fell into Japanese hands. Two of the crew members, William Dieter and Donald Fitzmaurice drowned after ditching, following the raid. The rest of the crew from plane 6 was captured. Pilot Lt. Dean E. Hallmark was executed for ?war crimes? by the Japanese on October 15, 1942. Co-Pilot Lt. Robert J. Meder died in the Japanese POW camp on December 1, 1943. Navigator Lt. Chase J. Nielsen was a POW for 3 ý years prior to his release. On the No. 16 aircraft, all five members were captured. Pilot Lt. William G. Farrow and Engineer/Gunner Sgt. Harold A. Spatz were executed for similar ?war crimes against Japan.? Co-Pilot Lt. Robert L. Hite, Navigator Lt. George Barr and Bombardier Cpl. Jacob D. DeShazer were taken as POWs but their execution sentences were halted by the Emperor himself, he chose to have them rot in prison for the rest of the war. (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Even though men did in fact perish for their country on this particular occasion, this was so in all wars past, present and future. Their loss was not invain, and did serve a purpose. The attack on Tokyo pointed out that ?The true pain had been psychological?a shattering blow to Japanese pride. Japan?s army and navy had failed to shield the homeland. Even more unforgivingly, they had not be able to safeguard the emperor.? (General James ?Jimmy? Harold Doolittle) Also this raid demonstrated Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle?s potent leadership abilities. The raid got Doolittle promoted to the rank of General, and he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions in the raid. This attack did change the course of the war in the pacific, in a way that made the Japanese realize that the US wasn?t limited in their militaristic reach. The raid did prove the US was going to fight to the death for democracy and also that Jimmy Doolittle was one of America?s most premiere leadership figures.