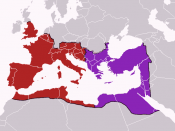

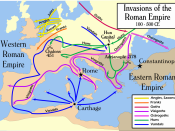

In the year 476, the last Roman emperor was deposed. Over the previous two centuries, Barbarian invasions had brought the once-mighty Rome to its knees, and this is taken as the final fall of the Roman Empire in Western Europe. What are the political, economical and social implications of this event, and to what extent does it constitute a true turning-point in history?

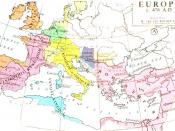

In the period immediately after 476 it is possible to see the structure of medieval Europe emerging. Most obviously, the empire was quite quickly replaced by nation-states, vaguely resembling those Europe consists of now: a Frankish Kingdom that would become Spain, and an Ostrogothic Kingdom that would split into Italy, Greece, and Balkans. There would be much movement of borders and struggles for superiority before the countries we now recognise would appear (after all, Germany as we know it only arrived in 1870's). But the pattern of a diverse continent with numerous small states was quickly established.

A clear consequence of the birth of these nation states was the beginning of modern monarchies. Late Roman leadership had fluctuated between elected, appointed and hereditary emperors; in the new Barbarian kingdoms, the hereditary principle became the standard. Educated statesmen were replaced by hardened warriors who earned their positions of power by warfare. Furthermore, elected institutions such as Senates were abandoned, kings ruling by decree, with appointed advisors but no elected officials. Democracy in any form was not to return for several centuries.

Furthermore, the Church began to separate from the state. Unlike in the East, where the emperor lay claim to control of the Church as well as government, God's representative in Medieval Europe was deemed to be the Bishop of Rome, who soon became the only bishop to be known as 'Pope'. Kings, on the other hand, ruled...