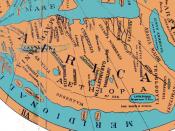

Of all the tribes studied in Africa, the Garamantes seem to be the most mystical of them all. Little information has been uncovered and much skepticism still remains about the definite position of the tribe. Written records from ancient authors, such as Herodotus, Pliny, and Virgil, and a few carved reliefs, are the only way to piece this society together. Also, there are few archaeological investigations to prove their existence. The impression the Garamantes left on these ancient authors was one of a troublesome and barbaric people. But more recent studies conflict with this assumption, and perceive them as being a major force in the Sahara desert from 500 BC- 500 AD.

The tribal confederation of the Garamantes, whose heartland was the area known today as the Fezzan, was the dominant force in the Libyan Sahara for much of the antiquity. Their existence is traced back to around 500 BC.

The Garamantes seemed to be fierce and endowed with extreme physical stamina. Their interest and curiosity of neighboring providences led them to explore land and inevitably brought them in conflict with Rome. Although they were remote geographically, it did not save them from warfare with enemies. Throughout time, the Garamantes appear to have become more peaceful and opened their land for trading and other purposes.

The race of the Garamantes is said to be " white Mediterranean, naturally colored black"ÃÂ. Too little evidence leaves this to be easily argued. Remains verify their physical structure as being "bird-like and small headed"ÃÂ. Portraits of women reveal they were strikingly elegant and beautiful. Some men of the tribe were heavily tattooed on their upper bodies and face. As a mark of social status, some men wore long robes that fastened on the shoulder. The women were as richly endowed with ornaments and animal skins. Greek and Latin authors frequently called the tribe "naked Garamantes"ÃÂ, but evidence makes it clear that they were not so simple. Fragments of leather in Garamantes tombs reveal the skins of lions, panthers, and bears. Over their elaborate garments, they also wore a cloak, and under it a tunic, or nothing except a belt from which hung a sheath to cover and protect. Female garments represent a long skirt falling well below the knees and as equally elaborate.

One important custom, previously mentioned, was tattooing, which is widely shown in Egyptian carvings of Libyans. Patterns are seen on the arms, lower legs, and occasionally on the upper body. It is thought of as being restricted to all men and used for only chiefdom positions. Paintings found show several men heavily tattooed, while others had none. Another custom shows the importance of dressing the hair. The Garamantes were known to wear their hair in a number of different ways. The most common form shows men with pointed beards, hair brushed back over their necks and sometimes with small braids. The women allowed their hair to grow long and would commonly decorate their head with Ostrich feathers. Other Libyan paintings portray women with high plumes in their hair with a bird's wing upright on their head as a sign of when they were traveling.

Specific beliefs on religion are not certain, but Daniels concludes, "that something can be said of the beliefs and customs of other Libyan tribes, and there is no reason to think that those of the Garamantes were radically different"ÃÂ. Herodotus records that the nomads only sacrificed to gods of the Sun and the Moon. During the sacrifice, they would cut off an ear of a victim and throw it to the gods. There is more evidence of a solar worship and fewer for a lunar cult.

Burial customs of the people are described as Germa mausoleums. One characteristic of the Berber people, witch the Garamantes are considered, was the development of couchets. These are described as roughly hollowed out stone bowls and thin upright slabs of stone placed against their eastern, outside, face. In some cases, imported Roman pots take the place of stone bowls. In only two burials, cremations have been found. Inhumation was practiced among the tribe, so some skeletons found were crouched, and sometimes extended. These mausoleum superstructures present steps and a podium. They are different from those of periods before, in that they contain no basil burial chamber. They show an effect of classical Roman architecture type of monument found in parts of eastern Algeria. These alterations should be seen as further evidence for the activity of Roman craftsmanship at Garama. The date of these monuments is still uncertain, "but the late first or second century is as good of guess as any"ÃÂ, states Daniels.

The specific type of governing used by the Garamantes is still quite unclear. But Pliny speculates there was a division into two castes, one aristocratic and the other vassal, and government by a sort of feudal monarchy.

The tribe built houses of dry stonewalls construction enclosed by a terrace wall for penning stock. Gradually, mud-brick houses replaced stone structures. Most houses were flat, single or two-bedroom units over 100 feet in length. The pottery used suggests a late first century B.C. or first century A.D. context.

Despite an average rainfall of a half-inch each year, the Garamantes successfully cultivated their settlements. They connected underground irrigation canals to natural fossil water supplies. With these canals, food production rose and population expanded, allowing the tribe to create towns and to expand their political control. The Garamantes reached its peak in the second and third centuries AD, and new archaeological evidence suggests it became one of the Roman Empire's main trading partners. It is believed that large quantities of African gold, ivory, salt, semi-precious stones, and slaves were supplied to the empire via the Garamantes kingdom. One of the most characteristic possessions of the Garamantes, Herodotus recalls, is "their backward grazing oxen. The reason is that their horns curve forwards, so they walk backwards while grazing"ÃÂ. They are also believed to have four-horse chariots or wagons used to cover the vast amount of African territory.

Hopefully, future studies will bring answers to the thousands of unanswered questions about the Garamantes.

Bibliography Daniels, Charles. The Garamantes of Southern Libya. The Orlander Press: Hassocks, Sussex, England, 1970.