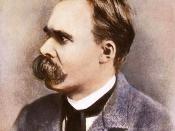

In On the Genealogy of Morals, Friedrich Nietzsche provides three essays which collectively challenge the belief that morality is an eternal, absolute truth which originated from some otherworldly source. The first essay, "Good and Evil, Good and Bad," introduces the concepts of "master morality" and "slave morality." This distinction is the foundation for the Genealogy's subsequent analysis. In the second essay, "Guilt, Bad Conscience and the Like," Nietzsche explains how slave morality transformed and recreated the relationship between guilt and punishment. This in turn leads to what he calls "bad conscience." The final essay, "What is the Meaning of Ascetic Ideals?" discusses man's reaction to the creation of bad conscience and his attempt to overcome it. By demonstrating the evolving nature of conceptions of morality throughout history, Nietzsche attempts a genealogical method to unmask the motivations and meanings behind humanity's reevaluation of what is "morality." This attempt to find the underlying motivations of change represents Nietzsche's greatest contribution to philosophy.

Despite this, his line of reasoning can fairly be seen as questionable and remains vulnerable to much criticism. Foremost among On the Genealogy of Morals' shortcomings is Nietzsche's tendency to underestimate the values of moral issues such as good, evil, guilt, and free will. This results from the fact that much of Nietzsche's conceptions of moral evolution draw more heavily on his own imagination than on the actual historical facts.

In "Good and Evil, Good and Bad," Nietzsche suggests that ideas of "good," "evil," and "bad" depend entirely on perspective. Contrary to earlier English philosophers, he makes the case that the concepts of "good" and "bad" did not arise from man's characterization of selfless actions which were of benefit to others. Instead, he supposes that the privileged segments of society defined "good" as those things which described themselves...