At the start of World War I each nation expected its army to win an immediate and decisive victory. The largely unrealistic and overly optimistic attitudes and sentimental views of war, held by the majority of British people in 1914, is reflected in the poetry written in the early part of the war. No one foresaw a long war dominated by the stalemate of trenches or the gigantic social upheavals to follow.

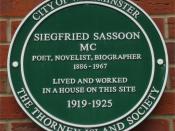

The war was seen almost as a Christian crusade that would bring a new nobility to those who took part in it. Rupert Brooke's 'I. Peace' has images of religious calling, inspired youth, walking with restored strength and refreshed senses and diving into 'cleanness'- images of baptism and absolution associated with the doctrine of 'muscular Christianity'. Even Siegfried Sassoon's early poems display this idea of spiritual cleansing afforded by the war: 'The anguish of the earth absolves our eyes Till beauty shines in all that we can see.

War is our scourge; yet war has made us wise, And, fighting for our freedom, we are free.' (Absolution) Many poets published poems to encourage people to enlist in the army. Special spaces were allocated in newspapers for such 'recruiting poems'. 'Fall in' by Harold Begbie is an example of this propaganda verse. War had not yet come to be regarded as a wasteful tragedy, and this jingoistic poem soon gained considerable popularity. It was sold on pins and sheets to raise money for the war and, within a month of publication, was set to music and played in music halls throughout the nation.

The poem calls young men to enlist in a mood of optimistic exhilaration. The straight-forward language, regular rhyming pattern and structure of the poem lends it to being put to music and so is in keeping with the jingoistic attitude towards war that the poem embodies and allows the propaganda to appeal to all classes. This regular rhythm and structure could also be seen as mirroring the conventionality of the views expressed in the poem. It illustrates the negative pressure applied to those who did not enlist, claiming they will be ignored by girls, thought a coward by their children and forever regret having 'funked'.

War is trivialised, 'the fight' and the repetition of the diminutive 'sonny', in each verse, together with references to 'the lads' and 'the picture show' direct this call to young men. The poem speaks directly to them, in an accusatory manner, 'But where will you look when they give you the glance that tells you they know you funked?'. It promises a short, chivalrous war and a safe return in the first stanza, and goes on to contrast this with the threat of eternal shame for those who do not enlist, 'Your old head shamed and bent'. The poem claims that the only way of redeeming one's honour, having not already 'rushed to beat' the German 'foe', is to enlist before it is too late, '..I was not with the first to go, / But I went, thank God, I went'. War is glorified, '..the War that kept men free', with those who fight it shown as 'brave and strong', and, as with many poems written early in the war, it is implied that to enlist is one's Christian duty, 'And Britain's call is God's'.