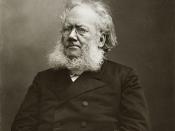

In the essay Ibsen, Anatol Lunacharsky argues that Henrik Ibsen, despite protests in his plays, did not know what he protested since he could not embrace, yet could not condemn the actions and follies of the middle class people, his subjects, nor predict a bright future for them. Moreover, the author makes a second point that Ibsen, a petty bourgeois himself, recognized the many vices of the middle class and therefore, resented his peers deeply. Thus, the reader will disagree with the first point due to fallacies such as begging the question and generalization, prevalent in the author's argument, and agree with the second point because of the author's analyzation of Ibsen's plays, as well as his interpretation of Ibsen's poetry.

To understand the fallacies present in Lunacharsky's argument, one must consider the socialist viewpoint of this critic. Lunacharsky, who served as Minister of Education under both V.I.

Lenin, and Yosef Stalin during the heyday of communism, approaches the justification of his first point somewhat idealistically and naively. To undermine the values of the petty bourgeoisie and show weaknesses in Ibsen's dramas, Lunacharsky over generalizes, conforming to the criteria imposed by a communist work. For example, Lunacharsky states, "It is obvious that the prophets of this petty bourgeoisie had to exalt individualism, strong and fearless personality, indomitable will; these were not merely the basic virtues inherited from their ancestors of the golden age of Norwegian peasant-fisherman economics, but constituted as well, valuable support in the bourgeoisie's active resistance to capitalist elements" (2). The sentence begins on a falsely confident note; Lunacharsky assumes that, "it is obvious" to all readers that the modern Norwegian middle class inherited the preceding characteristics from their subsistent peasant forefathers, as a whole. Yet, nowhere does the author note the possibility that many bourgeois Norwegians did not necessarily come from a "peasant-fisherman" background or resist the advances of capitalism. Lunacharsky, an intellectual yet a high-ranking communist, mass-labels the Norwegian middle class to justify his point to a socialist audience. By using this example of generalization, the author hopes to show his readers that the bourgeoisie emerged from generations of peasants who spurned capitalist ideals. Thus, Lunacharsky seems to argue, Ibsen and fellow members of the Norwegian petty bourgeoisie would fare better returning to their roots and denouncing capitalism. However, he notes, this became impossible for Ibsen, who out of obligation could not renounce his identity as a member of the middle class. This argument, he hopes, will appeal to his point that Ibsen has no goal in mind when he protests certain aspects of middle class life in his dramas since he knows without embracing socialism, the middle class will become extinct.

The author also uses begging the question when he attacks Henrik Ibsen and his dramas within the essay. Lunacharsky states, "His trouble lies not in the fact that he seeks a working language with which to express great thoughts and feelings, and is therefore obliged to create new words not hitherto available to him -but in the fact that he is not certain of what he wants to say, and thus speaks unintelligibly: let the public think there is something important behind the cryptic language" (10). Once again, he hopes to satisfy the communist audience by proclaiming that Ibsen, subconsciously aware that the capitalist bourgeoisie had no future, resorted to ambiguous language since he could not end his plays protesting a something concrete. Furthermore, Lunacharsky, to weaken the effect of Ibsen's dramas to an extent, overlooks the possibility that Ibsen's writing may strike other readers as a work of clarity. By stating that as a fact, Ibesn does not entirely know what to say, Lunacharsky further discredits his argument because Ibsen, an artist, wields artistic license to express what he wishes in clear or ambiguous terms. Moreover, Lunacharsky, who wrote this essay almost thirty years after Ibsen's death, can never truly know that Ibsen did not have a goal to his protests. This fallacy impairs the validity of Lunacharsky's first point because it does not thoroughly expunge the possibility that Ibsen had a message indeed. This argument seeks to prove the first part of Lunacharsky's point, that Ibsen did not know what he meant, whereas the previous fallacy hopes to prove the second half, that Ibsen's disgust at middle class follies and doubt of a middle class future prompted him to write so ambiguously. However, Lunacharsky stresses, Ibsen could not condemn his people because of the obligation he felt towards them. Thus, the preceding examples of begging the question ultimately undermine Lunacharsky's arguments because they serve merely as examples of subtle communist propaganda gearing to demote the lure of capitalism.

Yet the theorist Lunacharsky's second point sounds agreeable, on the other hand, because the author raises proof from analysis of some of Ibsen's dramas, as well as interpretation of Ibsen's poems. To prove the point that Ibsen resented and disliked the middle class to a formidable extent, Lunacharsky analyzes several of Ibsen's famous works, including Peer Gynt, Brand, and An Enemy of the People. Referring to Hedda Gabler, Lunacharsky states, Realistically, (as Eleanore Duse conceived the part), the play is a profound and brilliant study of a shallow, hysterical woman striving for startling effects and for chances to demonstrate her power-cowardly in the face of scandal, devoid of any interest in the constructive aspects of life, a possessive and almost spineless being. However, the demands which Hedda makes on the people around her are so reminiscent of Brand's that many critics considered that she was a much nobler character that Thea [Mrs. Elvsted], that she was a positive type personifying Ibsen's ideal woman. This confusion of the critics was not accidental. Here Ibsen seemed to direct his irony against himself (8-9).

In other words, Lunacharsky means that Ibsen intends to develop Hedda not as an ideal woman, or feminist icon, but as a bored, pretentious, and virtueless woman who overlooks morality and compassion to quell the tedium of life as a bourgeois. Despite this, Lunacharsky notes, most critics glorify Hedda as a woman's hero. To prove this argument, Lunacharsky alludes to the great Italian actress Eleanora Duse's portrayal of Hedda. Furthermore, Lunacharsky shows Ibsen's dislike of his middle class peers, as well as himself with the last sentence. Thus, the author implies that in this play, Ibsen's goal did not entail creating a feministic heroine, but instead, exposing the foibles of the bourgeoisie. This analysis, complete with the assertion of a stage actress, aids in proving the point that Ibsen often resented the very layer of society from which he was born. Despite Lunacharsky's claim that Ibsen struggled between condemning and embracing the capitalism-minded petty bourgeoisie, his essay provides no logical evidence to uphold this claim. Lunacharsky, however, does succeed in proving Ibsen's discontent with his class.

Lunacharsky does extend this point to hint that Ibsen often felt embarrassed being a member of the petty middle class due to the extensive list of faults and vices the bourgeoisie boasted. He argues that Ibsen, despite being somewhat of an idealist who felt that individuality was a praiseworthy characteristic in any man, displayed pessimism when confronted with the inexhaustible vices of the middle class. In one of his personal poems, Ibsen wrote, "Traverse the land from beach to beach/ Try every man in heart and soul/ You'll find he has no virtue whole/ But just a little grain of each." Thus, Lunacharsky conjectures, "â¦Ibsen understands perfectly this empty external evanescence is only and ideal, entirely unrelated to actuality" (5). Ibsen says that entirely virtuous people rarely spring up in society, no matter how far one travels. Although he means this generally as an observation of human kind, he also applies it to the bourgeoisie. It seems that despite Ibsen's idealization of elements of his society, within his soul he fully understands the shortcomings of his society. Ibsen knows the dubious traits of his peers, and subconsciously or not, they make appearances in his dramas. Hence, Lunacharsky's second point exposing the resentment of Henrik Ibsen can be dubbed valid due to the proof exhibited in the preceding poem.

Thus, in the essay Ibsen, Anatol Lunacharsky argues that Henrik Ibsen, despite protests in his plays, did not know what he protested since he could not embrace, yet could not condemn the actions and follies of the middle class people, his subjects, nor predict a bright future for them. He makes a second point that Ibsen, a petty bourgeois himself, recognized the many vices of the middle class and therefore, resented his peers deeply. Thus, the reader will disagree with the first point due to pervasive fallacies such as begging the question and generalization, but agree with the second point due to the author's analyzation of Ibsen's plays and interpretation of Ibsen's poetry.