Berryman was born John Allyn Smith, Oklahoma, the son of John Allyn Smith, a banker, and Martha Little, formerly a schoolteacher. The family moved frequently, finally settling in Tampa, Florida, where his father speculated in land, failed, and in 1926 committed suicide. Three months later his mother married John McAlpin Berryman, whose name was given to the son.

The new family moved to New York City, but hard times followed the 1929 stock market crash; young John attempted suicide in 1931. The next year he enrolled at Columbia University, where he flourished and published poems in Columbia Review and The Nation. After graduation, he studied two years at Cambridge University in England, meeting W B. Yeats, T S. Eliot, W H. Auden, and Dylan Thomas. He tried playwriting, won the Oldham Shakespeare prize, and published poems in Southern Review (1937).

In 1939, he was hospitalized for epilepsy, although he was actually suffering from nervous exhaustion, a condition that would recur in future years, worsened by alcoholism.

For the next twenty years Berryman established his academic credentials, beginning with reviews and a critical edition of King Lear (never published), and articles on Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Robert Lowell. He also wrote on Marlowe, Shakespeare, Walt Whitman and Theodore Dreiser. In 1950 he won the American Academy award for poetry.

His private life, however, was crumbling on account of his alcoholism. He separated from his wife in 1953 and was dismissed from Iowa after his arrest for public intoxication and disturbing the peace. By 1955, assisted by poet Allen Tate, Berryman moved to Minneapolis and was appointed lecturer in humanities (separate from the English department) at the University of Minnesota, which became his home for life. The cycle was nearly complete, as he now lived thirty miles from his suicidal father's birthplace. At this time he began The Dream Songs, his most significant work.

After checking into alcohol rehabilitation once in 1969 and three times in 1970, Berryman experienced "a sort of religious conversion" in 1970. His research on Shakespeare continued, but the fatal cycle refused to be broken: haunted by his father's suicide and with his youngest daughter just six months old, Berryman jumped to his death off the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis.

Dubbed a confessional poet, Berryman produced verse for thirty-five years. The most celebrated, Dream Songs, intensely personal, the poems relive a childÃÂs attempt to establish order in a disintegrating family. The most hopeless stave, number 145, speaks of the imaginary character through which the poet projects misgivings about life and sanity. Narcissistic and self-serving, Dream Songs characterizes BerrymanÃÂs devastating need for a prop/support, whether grandstanding, alcohol, fantasy, or poetry.

About the poem (29)The Dream Songs (1964) won the Pulitzer Prize. In all, The Dream Songs, published under that title in 1969, stretched to 385 songs and resembled a sonnet sequence, with each song composed in a three-stanza format, eighteen lines with rhyme. The poems are much too difficult, packed, and wrenched to be sung. They are called songs out of mockery because they are filled with snatches of Negro minstrelsy. The dreams are not real dreams but a waking hallucination in which anything that might have happened to the author can be used at random. Anything he has seen, overheard, or imagined can go in.

Their protagonist, Henry, is a white middle-aged American who talks about himself in first, second, and third voices and listens to his unnamed Friend, a white American in blackface speaking Negro dialect. Henry is greedy, lusty, and ill-tempered; he is essentially Freud's Id. His Friend is conscience, and their dialogue works itself out, as analysis in the therapist's office, each song approximating a session on the couch. Henry is allowed speaking with all of Berryman's intangible things, whether drunkenness and shameless sexual drives or his fatherÃÂs suicide.

Dream Songs is larger and contemporary and crowded with references to news items, world politics, travel, low life, and Negro music. Its style is a collection of high style, Negro and beat slang, and baby talk. There is little sequence, and sometimes a single section will explode into three or four separate parts. At first the brain aches and freezes at so much darkness, disorder and oddness. After a while, the repeated situations and their racy chatter become more and more enjoyable.

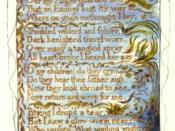

The First StanzaThis particular song is about Henry's response to the death of his father. Here is a sad song of loss that appears not in HenryÃÂs deprivation itself but in the arrival of that feeling of loss to his mind in the form of an oppressive psychic visitation: "There sat down, once, a thing on Henry's heart." In the first sestet, neither the nature of the thing that "sat down . . . on Henry's heart" nor the time of its intrusion is made clear. "The little cough somewhere, an odour, a chime" that "Starts again always in Henry's ears" suggest that these are possible childhood memory productions, recalling in some way the cause of the oppression that "sat down, once . . . on Henry's heart,". And HenryÃÂs inability to ÃÂmake goodÃÂ starts in his ears as "an odour". Yet, one possible meaning of to "make good" is to succeed or follow a demand parents are tending to place on their children; another suggestion is to "make good" on a debt or to make up for an error or misbehaviour. The poem may be an elegy for childhood losses. But here, a child's consciousness is suggested not through direct experiences but through the preservation of childlike forms of speech ("in all them time," "so heavy," "could not make good"). These childish forms of speech convey Henry's feeling of his own incomplete maturity, the struggles caused by the fact that a part of himself remains locked in childishness, emotionally uncompleted.

So, this very stanza is about a childhood memory concerning the unforgotten funeral itself as (the "cough," "odour," and "chime") indicate. The experience is described in intensely private terms; the "thing" is on HenryÃÂs heart, the cough "in HenryÃÂs ears." I believe it to be the remorse, and terror and paranoia activated strangely to sit down on HenryÃÂs heart (which is the emotional power or source a child can resort to when exposed to extreme situations). The ÃÂthingÃÂ or feeling of being unloved, that has broken his heart seems simply a heaviness to which no action can adequately respond whether this action was that of ("weeping") or that of (sleeplessness) which is quite a lot amount of time. So dominant that any sound or smell recalls it.

The Second StanzaThis part adopts the logic of an adult. The voice of the man becomes one with the voice of the child here, as their sense of remorse and nightmare, though unexplained, is combined and shared. ItÃÂs as if two widely separated parts of a manÃÂs life had somehow united. And the reason for his seemingly unreasonable terror is that in spite of all his wives had done to make him feel otherwise, there was BerrymanÃÂs overwhelming sense of being unloved. One can share BerrymanÃÂs sensing that, as his father had shown him by blowing his heart out with a single gun shot. Or Eileen, his first wife, turning from him as they drove south together from Paris to Siena in the spring of 1953. For him her image would remain forever linked in another dream song with the sorrowing face of the betrayed Christ, the two accusing faces becoming for him "the grave Sienese face a thousand years / would fail to blur the still profiled reproach of." No wonder he had come in time to fear and hate the world with an intensity almost approaching paranoia.

The Dream Songs emerged out of a period of intensive dream analysis for Berryman. And the poem's sudden shifts and surprising juxtapositions reflect his extensive exploration of and immersion in unconscious experience: Henry feels the reproach of that grave Sienese face, no doubt Virgin Mary or saint, and the language evokes other religious and ceremonial elements (such as "the bells").

The Third StanzaThese lines perhaps describe the morning horrors of an alcoholic who has no memory at all of what he may have done during a blacked-out period the night before, and who automatically fears the worst. Though nobody is ever missing, Henry knows that he is capable of "ending" someone and hacking her up, which is a misogynous fantasy, and this helps account for his identifying himself with people devoted to crimes or brutal murders.

This particular poem has the quality of a dirge (a song or hymn of grief or lamentation) and is peculiar in part because the reader discovers that there has been no death, certainly no murder, since "Nobody is ever missing." Despite feelings of grief and guilt, particularly over an urge to commit violence to women, there seems to be no deceased object nor any specific action to which Henry can attach his disturbing feelings of guilt and grief. Yet the feelings of guilt and grief remain, and they are characterised by unusual intensity and duration: "so heavy" and so lasting that "weeping, sleepless, in all them time / Henry could not make good."Berryman perhaps had reasons to be misogynist, the first one, fearing his mother, both as a possessive and judgmental presence in his life and as his father's possible murderer. In addition to his wife abandoning him. Consequently, the unconscious desire to ÃÂend anyoneÃÂ and ÃÂhacks her body upÃÂ came about. And though there is no indication of an actual murder of a woman, his father, however, was definitely, if ambiguously, "missing." It was in Berryman's youth that the violent death of his father and his own abrupt transformation from the Catholic John Smith of Florida to the unbeliever John McAlpin Berryman of Manhattan occurred, in the context of abuses whose persistent reality the poem chooses not to acknowledge openly. The psychological conflict between terrified certainty of murdering someone, a woman in particular and absurd logic of missing no one or as the poem suggests (ÃÂnobodyÃÂs missing') is an outcome or a result of the obsessive and habitual restless ÃÂreckoningÃÂ or thinking.

Finally, in the last sestet, he acknowledges almost in defeat the social world of others, all those who persist in surviving despite his dreams of violence, and the cause of the "reproach" is now identified, who remind him that the thing on his heart is only private.

The Structure- [Berryman has been asked "what structural notion" he had in mind while writing ÃÂ ](I did not begin with a full-fledged conception when I wrote the first dream song. I donÃÂt know what I had in mind. Henry is accused of being me and I am accused of being Henry and I deny it and nobody believes me. Various other things entered into it, but that is where I started. The narrative such as it is developed as I went along, partly out of my gropings into and around Henry and his environment and associates, partly out of my readings in theology and that sort of thing, taking place during thirteen years ÃÂ awful long time ÃÂ and third, out of certain partly preconceived and partly developing as I went along, sometimes rigid and sometimes plastic, structural notions. )- The pattern of the poem is that of three stanzas or sestets with six lines each. The length of the lines is irregular as each line is relatively a continuous long sentence. The rhythms are more complex, vary from strong regular ones as (years-ears, time-chime, mind-blind) or non rhyming ones as (heart-good, ghostly-thinking, did-found)- Alliteration: is found in the (h) sound in (so heavy, if he had a hundred years)- Anaphora: is found in the 3d stanza (but never did Henry, as he thought he did)- Ampersand: used to make the poem sounds more informal in the 1st stanza, the 3d line (&more, & weeping, sleepless, in all them time) and the 3d stanza, the 4th line (he knows: he went over everyone, & nobodyÃÂs missing.)