Jose Guadalupe PosadaJose Guadalupe Posada is one of the most celebrated popular artists of the Americas. He greatly influenced the generation of Orozco and Rivera, who both admitted in Posada's time to admiring and following this notable famous artist. Over his lifetime, Posada is said to have created over 20,000 original prints and in fact prints are often called posadas after him. Posada is in the distinguished tradition of cartoonists who double as political and social commentators.

Posada was born in Aguascalientes on February 2, 1852. He grew up in an area known for agriculture, textile production, and ceramics. His early education was directed by his brother, Cirilo, a country schoolteacher, who taught him to read, write and draw. Posada discovered his talent for copying the artwork he saw and began to copy anything whether it be religious cards or small printed pictures.

As a young man, Posada apprenticed himself and began employment in the workshop of Trinidad Pedroso, who taught him lithography and engraving.

Before he was out of his teens, Posada was creating political cartoons and satirical illustrations for the small newspaper El Jicote.

In 1871 he suffered his first encounter with political repression. One of his targets had been the regional boss, Jesús Gómez Portugal, who was then out of office. Gómez, who did not take kindly to being mocked, returned to power and Posada and Pedroso were forced to move to León, where they set up another print shop. Posada made lithographs and engravings in wood that illustrated small boxes of matches, documents and books. Within a year the pair were heavily involved in a variety of activities: commercial and advertising work, illustration of books, the printing of posters and representations of historical and religious figures.

Posada became familiar with the illustration style of the day, and incorporated his own sensitive observation skills to his work. His ability heightened, and eventually Posada set up his own illustration studio in Mexico City during the late 1800's.

In 1883 he was hired by the local Preparatory School as a teacher of lithography. A disastrous flood struck León on June 18, 1888, and Posada was forced to relocate to Mexico City. In Mexico City he went to work at a publishing company run by Ireneo Paz, the famed liberal journalist. Posada, whose vigor and dedication to work were legendary, began to submit drawings and engravings on a regular basis to such well-known periodicals as La Patria Ilustrada, Revista de Mexico, El Padre Cobos, Los Almanaques de Padre Cobos, El Ahuizote and Nuevo Siglo. All this activity kept Posada so busy that he had to open two additional workshops. Concurrently, at the request of Paz, he was drawing both political cartoons and incredibly realistic sketches of daily life in the old San Pedro and San Pablo quarter, near the Merced Market.

Posada was an expert printmaker. Working in engraving, etching, or woodcut techniques, his personal style was immediately recognizable throughout Mexico. His illustrations were printed on sheets of colored paper and sold by street vendors at fairs, markets, and in the plazas. Each print was inexpensive, and the meaningful quality and everyday themes of Posada's drawings made them very popular with the common people of Mexico.

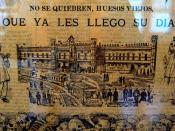

Unlike other social satirists, there was nothing snobbish about Posada. In 1880 Antonio Vanegas Arroyo and his son Blas came to Mexico City from Puebla and established a press with the goal of producing inexpensive literature for the masses. This literature sold mainly in plazas and market places. Posada illustrated journalistic broad sheets which were one page stories about newsworthy events for Arroyo. Natural disasters, political intrigue, crime, and folk tales all became subject matter for this trio. These ideas were based on the principle of bringing a popular, antiestablishment message to the mass of citizens who lived so miserably under the Porfirio DÃÂaz dictatorship and ultimately Posada went on to extend sympathy to the workers and peasants who became revolutionaries in 1910. The people of Mexico were fascinated by the stories, written in the poetic form of a corrido, a Mexican ballad. Those who were unable to read were fascinated by Posada's illustrations. Some of these sheets became so famous and sought after that they were reprinted by the thousands, occasionally reaching a publication of over a million copies. Venegas and his son also founded a number of leading newspapers, among them El Centavo Perdido, La Gaceta Callejera and El BoletÃÂn to which Posada contributed thousands of drawings.

Both Jose Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera visited his Posada's studio and count his work as important to their artistic development. Rivera paid tribute to Posada in his mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda. In that mural, Rivera chose to include the image known today as "Catrina," a well-dressed female skeleton, originally made public by Posada. Because Posada's art was created for the masses and not the elite, artists like Orozco and Rivera saw him as an important figure in the creation of a truly Mexican art style.

The festivals of Mexico are known throughout the world for not only their colorful decorations, lively music and extravagant parades, but their cultural significance also. Los Dias de los Muertos, the Days of the Dead, are no exception to this pattern. Frequently misunderstood by those of other cultures, these festivals honoring the dead are meaningful holidays celebrated during the year in Mexico. The art of Jose Guadalupe Posada has come to be closely associated with both the Days of the Dead and the Mexican artistic tradition.

Taking Mexico's traditional Day of the Dead (November 2) celebration as his theme, Posada would stage shows with skeletons in working class barrios, in suburban communities and even in the houses of the rich. During these productions the skeletons would ride bicycles or be garbed in the latest finery. His use of skeletons as a metaphor for a corrupt society ranks Posada as a pioneer expressionist. Posada supplemented morbid humor with satires against unethical and dictatorial politicians. For these offenses, he was thrown into jail on several occasions. The images of skeletons in Mexican prints is founded in the work of Santiago Hernandez, a political satirist. His work, done in the 1870's, depicts politicians as skeletons, or calaveras. The intent of Hernandez's work was, to provoke distaste for the political figures instead of being humorous. Posada's calaveras continued this tradition, but with the exception that many of his drawings were intended to poke fun at people from all walks and stages of life, not just politicians.

With the popularity of the skeletons, death became accepted as democratic, since after all, every person would finish by being skull. Posada's skull images were sold in the streets, and were well received by the people because of both their content and accessible price.

The calaveras of Posada are his most recognized work today. People adorn their Days of the Dead altars with his images and cut them into their banners. His calavera images reflect the diversity of Mexico's population in his time. For us, these images can remind us that we will all face the same end, death, despite the variety of positions we occupy presently.

Because this gifted and hardworking man was continually out of political favor, he died on January 20, 1913, as poor as he had been born. He was buried in a sixth class grave (the lowest category) in the Dolores Cemetery. Since nobody claimed the remains, they were thrown out seven years after his death. As with many great artists, the recognition that eluded Posada during his lifetime came after his death.

Bibliography Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). 29 April 2000. Posada, José Guadalupe. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition Copyright é1993. 29 April 2000. Metcalfe, Amy Scott. The Days of the Dead and Mexican Printmaker Jose Guadalupe Posada .

Copyright 1999 CRIZMAC Art & Cultural Education Materials, Inc. 29 April 2000. Tuck, Jim. Mexico's Daumier: Jose Guadalupe Posada 1852-1913. 29 April 2000.