My name is Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain; I am going to tell you a brief history on what the United States was like before I was born. In 1788 the United States became an independent nation. It was made up of thirteen states and owned several territories on the western side of the Mississippi River. The countries population was about four million people that lived mainly in the eastern states. In 1787 the country expanded its boundaries and accepted a new territory to the original 13 colonies. The new territory was called the "Northwest Territory." The Northwest Territory was in equal basis to the laws and rights of the eastern states. The government formed states out of the territories west of the original 13. Ten new states formed between 1791 and 1820. Through the years the government also purchased many states form other countries, such as Florida (from Spain), and the Louisiana Purchase (from France), which almost doubled the United States in size.

The United States was forming different sections during the early 1800s. In the Northeast big cities and industry thrived, and the South consisted of large farms. These different sections had different views. Slavery was the biggest issue that the north and south disagreed on. People in the south said that they needed slaves for help with harvesting crops. But people in the north wanted slavery to be abolished.

I was born September 8, 1828, in Brewer, Maine. Maine is the northern most state on the Atlantic coast of the continental United States. I grew up on a 100-acre farm, the oldest of five children. I had three brothers: Horace, John, and Thomas and one sister Sarah. My mother, Sarah Dupee Brastow Chamberlain, was a woman of great wit, a gentle but firm hand, and strong Christian faith. My father, Joshua Jr., was a strict but generous man, who taught his children to think for themselves, but who never let his children forget who was boss. As a boy I briefly attended Whiting's Military and Classical School, my father intended to fit me for West Point. But my mother wanted me to study for the ministry. I didn't care to do either, but I especially didn't care to go into the army in peacetime. I eventually conceded to my mother's wishes, but only if I could serve as a missionary overseas. In 1846, I decided to attend Bowdoin College in Brunswick. My years as a Bowdoin student were filled with studies and other activities.

At First Parish Church, I first set eyes on the pretty, dark-haired Frances Caroline Adams known to friends and family as Fannie. She was the adopted daughter of First Parish Church's pastor, the Rev. George Adams; Fannie had been born and raised in Boston, but was sent at a very young age to live with her father's nephew and his wife. I fell head-over-heels in love with Fannie, a very well educated young woman herself, skilled in both music and art. She was also very strong-willed and rather fond of "fancy things", like elaborate clothes and furs. It was not an easy courtship. It seemed at times that Dr. Adams didn't think that I was "good enough" for his daughter, although that would change with time. There also seems some indication that Fannie did not have the same strong feelings towards me as I did towards her. But we finally became engaged in the fall of 1852. We agreed to marry after my graduation from Bowdoin, and after I completed three years of study at Bangor Theological Seminary. Fannie returned from Georgia in August 1855, in time to see me graduate from Bangor Theological Seminary, and take my Masters' Degree from Bowdoin (I received my Bachelor's Degree in 1852). I was also invited to give the Masters' Oration at Bowdoin's commencement in 1855. The speech, entitled "Law and Liberty" was a resounding success. My first public speech ever was at the1852 graduation! In the wake of the success of the speech, I was offered part of the work in the Department of Revealed and Natural Religion at Bowdoin (Professor Stowe was leaving to take another post at Yale). When the next term opened at Bowdoin, I was an instructor in Logic and Natural Theology and, as a tutor, I was in charge of the Freshman Greek class.

Fannie and I were finally married on December 7, 1855, at First Parish Church by Dr. Adams. In October 1856, Fannie gave birth to our first child, a daughter we named Grace Dupee. In November 1857 she gave birth three months early to a son, who only lived a few hours; it was a very sad Thanksgiving in the Adams house that year. But in October 1858 another son was born; after some anxious moments, the boy grew healthily and was named Harold Wyllys. Two other daughters would be born Emily Stelle in the spring of 1860, and Gertrude Loraine, born in the fall of 1865, but both would die before their first birthdays.

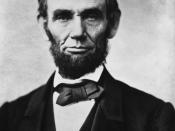

By this time, however, critical national issues overshadowed personal concerns and sorrows. The issue of slavery, and its westward expansion, caused emotional debate and violence for decades. The 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States signaled to many Southerners a new unpleasant way of life. One by one, eleven Southern states eventually seceded and declared themselves a new country: "The Confederate States of America." First and foremost in my political beliefs was that the United States was a Union of one people; the people living in the United States constituted the people of the United States.

On April 12, 1861, the guns of the state of South Carolina opened fire on the United State's Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, and the country was doomed to civil war. Thousands of men flocked to President Lincoln's call for troops to preserve the Union and their country.

At Bowdoin College, some upperclassmen enlisted immediately. Nearly 300 Bowdoin men would serve the Union cause. As time went on, it was clear this war would not be a short one and an "irresistible impulse" began to stir inside me, to get involved in the conflict. My desire to be "placed at my proper post" would be faced with personal, and professional, obstacles to overcome. My father, who had wanted me to go to West Point and become a career soldier, would declare the conflict "not our war". Fannie was opposed to me going she liked being a college professor's wife, and she didn't like the idea that her husband would be risking not only his life, but also the entire support of her and their children. Bowdoin College didn't want me to go, either.

On July 14, 1862, I wrote a letter to Maine's governor, Israel Washburn, requesting that I be placed in the army. Washburn knew that both my grandfather and father had served faithfully in previous wars. The governor relied on Maine's leading men to raise new companies of infantry to fill the state's quota for new regiments. I was confident that I could raise the number of men needed for an entire regiment.On August 8, 1862, I was mustered in as second-in-command to Colonel Adelbert Ames, a Regular Army officer, and a Mainer from Rockland.

I was placed in the 20th Maine, which was put into Federal Service in August 1862, as part of the Third Brigade, First Division, of the Army of the Potomac's Fifth Corps. The first time the 20th Maine saw major battle action was at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862. The battle was a disaster from the start; the reinforcements were late in coming, giving Lee's men time to concentrate and form up behind a convenient stonewall. The Confederates waited for the Union troops to get within range, and mowed them down like grass. The 20th Maine was part of the last charge of the day, fighting with their comrades in the Center Grand Division. We lost four killed, and 32 wounded.

On June 23, 1863, I took command of the 20th because I impressed General Griffin on assisting him with a retreat. I was in command as we set out for Gettysburg. After a long march, we arrived near Gettysburg in the early hours of July 2. In the middle of the night a messenger from General G.K. Warren, the chief engineer arrived, looking for troops to be sent to a place called Little Round Top, General Warren was atop the hill, overlooking the field, and watching Confederate Lt. General James Longstreet's men smash into troops of General Dan Sickles' Third Corps, and head for Little Round Top. Little Round Top was exposed and undefended, Warren saw the immediate danger, and sent messengers looking for men to get up there and defend the hill. The messenger ran into the 20th Maine's brigade commander, Colonel Strong Vincent, who took it upon himself to take his brigade (without waiting for orders from Division command) and get up to Little Round Top. They got there with only minutes to spare.

The situation for the 20th Maine was that it was taking a real beating, and time was running out, as well as ammunition. As my men fired their last rounds, they all looked at me as if to say: "What now?" Desperate times call for desperate measures, as they say. I decided to charge the rebels. The remaining 200 or so men of the regiment ran down the hill screaming hoarsely, bayonets at the ready. The shocked Confederates didn't know what to do, here were these bayonet-wielding Yankees bearing down on them when suddenly we were hit from the flank by musket fire! The 20th's Company B, led by Captain Walter Morrill, had been sent out on the extreme left, as protection. We found a stonewall to hide behind, and were joined by some Union Sharpshooters, who had been driven off Big Round Top by the Confederates. This was all too much for the exhausted Rebels; many threw down their weapons and surrendered.

The 20th Maine, once it got started charging, was hard to stop. We took, around 400 Rebel prisoners. In spite of our heroic charge, the day was not over for us. After an anxious night, we rested on Big Round Top. We lay there during the bombardment that preceded "Pickett's Charge" on July 3rd, but were too far away to be engaged in the fight on Cemetery Ridge. Before leaving Gettysburg, we bid farewell to our dead. We buried them in shallow graves, near where they fought and died.

Shortly after this I was ordered by my superiors to lead another attack on the confederacy. I thought the order was suicide, but I obeyed orders. In the attack I was shot through the hip and lost a lot of blood. I was carried off the field in a stretcher and the best surgeons and doctors helped me to regain health. I returned to battle in Petersburg on November 18, although still unable to ride a horse, or walk unassisted a hundred yards.

In the fight at the Quaker Road, March 29, 1865 a bullet had ripped through my sleeve to the elbow, and injured my arm, and traveled around my ribs before going out the back seam of my coat. Had it not struck the field orders book and the hand mirror in my pocket, it would surely have killed me. I coped with this wound and I coped with the pain. I participated in only a couple skirmishes with the confederacy after my arm wound.

Due to the overall efforts of the Union army the Rebels surrendered on April 9, 1865, General Grant had decided that a surrender ceremony should be held, in order to make certain to the Rebels that, indeed, the war was over. They were to hand over their weapons and their battle colors, but keep their side arms and their horses. I was selected by Grant to be the man to receive the confederate arms.

I was officially mustered out in August 1865, but applied for reinstatement, due to needed surgery for my Petersburg wound. My reinstatement was accepted, and I was finally mustered out January 15, 1866.

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, I returned to Bowdoin College as a professor. I tired of being a professor. I ran for governor of Maine. In September 1866, the largest majority in the state's history, up to that time, elected me Governor of Maine. During my terms as Maine's Governor, I undertook projects that were not just talked about, but instead were carried through. Not all of my proposals and stands on state and national issues were popular, however. For instance, I opposed the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in 1868. On the state level, I faced opposition on two major fronts: the state Liquor Laws, and capital punishment. After many terms as governor politics became overwhelming. In fact, after the stress of my political career, I began to look more favorably on a return to academic life. In early 1871, I was elected as Bowdoin's president. I took the position and made several changes.

In the summer of 1880, my father, Joshua Jr. died at the age of 79. In November of 1888 I lost my mother. My love for my wife, Fannie, remained strong all through the years. Sadly, Fannie suffered from eye problems most of her life, and by the turn of the century, had gone completely blind. In August of 1905, Fannie fell and broke her hip. On October 18, 1905, Fannie died in our Brunswick home, and was buried three days later in the family plot at Pine Grove Cemetery.

After I resigned as Bowdoin's president in 1883, I turned my attention to the business world. I worked out of Florida, New York and Maine, and my business ventures ranged from developing land in Florida, establishing the Ocala and Silver Springs Railroad, and holding stock in, and serving as president of, several companies, including New Jersey Construction, Mutual Town and Bond in New York, and Kinetic Power. My idealism and sense of duty to others were two factors that motivated me in business. After about a decade of trying to make a go of it in the business world, I gave it up.

After that I attended meetings and took an active interest in several organizations. Such activity, however, took a toll on my health; in December 1890, I was taken seriously ill, and confined to a room in New York City.

During this time of illness, the 30th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg approached, and many of my friends tried to obtain for me some concrete recognition for my outstanding service at Little Round Top. On August 17, 1893, I received what, to many, was a belated "thank you" from the government, the Medal of Honor. The inscription on the back read, â¦for distinguished gallantry at the battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863⦠In May of 1913, I made my last visit to Gettysburg, as Maine's representative on the planning committee for the 50th anniversary reunion in July of that year. I went once more to that southern slope of the hill, where my Twentieth Maine had won their undying fame. Sadly, my health wouldn't permit me to go to that great reunion. The heat would probably have killed me.

In August 1913 I visited my daughter's family at their summer home, I enjoyed sailing and spending time with the family. I was even considering writing a book about Gettysburg, but I soon fell ill again. This illness really sapped my remaining strength, and by January 1914, I was completely bedridden. This time there was no hope of recovery, and, with my son and daughter at my bedside, I died, quietly, at my home in Portland, on January 24, 1914. Three days later, on February 27, 1914, a military funeral was held at Portland's City Hall, under the charge of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion. Hundreds of people lined the streets as my coffin was taken from my Ocean Avenue home to City Hall. Two thousand people gathered inside City Hall, they included such dignitaries as Maine's governor, representatives of the governor of Massachusetts, officers of Bowdoin College, as well as members of the Loyal Legion and the Grand Army of the Republic. After the service, the funeral procession made its way on the Bath Road, to Pine Grove Cemetery. After the National Guard escort fired a salute of three volleys, my casket was lowered into the earth, to lie beside my beloved wife, Fannie. So ends the story of my life as, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.