Regionalization and Capital Movement

It is a well-known fact and dominant theory that development, defined as a process of improvements in a population's standards of living with associated structural or institutional change, requires access to and the accumulation of capital. Of course, capital, as wealth begetting wealth, or the sum total of society's productive resources, takes diverse forms: financial, physical, natural, human, and social. At issue in the development process is the accumulated stock of capital in these diverse forms, as well as their cross-national flows-international resource flows, if you will. As for money or financial capital, the most mobile form of capital, the international transfer process (the flow of capital) occurs in the form of bank capital (loans or debt financing), portfolio investments, and foreign direct investment. These transfers make up what can be termed private capital flows. Then there are also official capital flows via the operations of bilateral and multilateral aid or donor agencies.

The following table records in statistical form the volume of private and official capital flows from the North to the South. Of course, capital flows in other directions as well, and the table does not record the corresponding outflows of capital in the form of debt payments, royalty charges, repatriated profit, and corporate dividends. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development's World Development Report 2003, the combined South-North outflows of capital might well exceed the inflow.

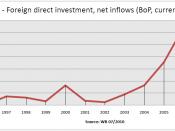

The international flow of capital is generally viewed as a catalyst and necessary condition of development. Foreign direct investment, a type of capital that is associated with the multinational corporation, is generally regarded as the "backbone of development finance." Portfolio investment, another form of private capital flow, tends to be more short-term and is much more volatile in its international operation and movements-so much so that in its unregulated form it has been held responsible for the financial crisis that hit Asia in the summer of 1997, with a devastating effect on the real or productive economies in the region.

Another important factor in international resource transfers, or the flow of capital, is the composition of this flow. As indicated in the preceding table, some regions (e.g., sub-Saharan Africa) are more dependent on official financial resource transfers than private capital for their economic development. Elsewhere in the South, especially in Latin America, the dominant flow of capital is private and increasingly composed more of foreign direct investments and less of bank loans (debt financing) or official transfers. The reason for this, although not immediately evident from the data, has to do with the agenda of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the 1980s: to push and pull Latin American governments into the "new world order" of globalized capital, deregulated markets, free trade, and private-sector-led development. The end result of these push and pull pressures was a deregulation of product, capital, and labor markets and a process of financial liberalization, as government after government in the region eliminated its restrictions on the operations of foreign direct investment. Much of this foreign direct investment was used not to induce a process of technological transformation, and thus increase productivity and economic growth, but to acquire the privatized public assets and forms put on the auction bloc in the 1990s.

Conceptual Overview

The 1980s gave rise to a counterrevolution, a movement to halt and backtrack on advances made all over the world on the basis of a state-led model of economic and social development. The counterrevolution included a call for a new world order in which global capital, the private sector, and trade would be allowed to operate free of restrictive government control in the search for profit, so as to usher in a new era of economic growth and general prosperity.

Table 1 Capital Inflows: External Financing by Region in the Global South | |||||||||

(U.S.$ billion) | |||||||||

1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

Latin America and the Caribbean | |||||||||

FDI | 30.5 | 44.4 | 66.1 | 73.4 | 87.8 | 75.8 | 69.3 | 42.0 | 38.0 |

Loans | 61.3 | 36.0 | 24.3 | 37.9 | 12.3 | -1.1 | 11.4 | 3.5 | - |

Private | 42.8 | 84.9 | 51.2 | 84.5 | 75.3 | 89.9 | 75.8 | 45.3 | 44.0 |

Official | 5.7 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 5.2 | - | - |

Asia | |||||||||

FDI | 2.3 | 4.2 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 9.0 |

Loans | 5.2 | 0.1 | -3.8 | 13.0 | -1.7 | -3.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

Private | 18.7 | 15.0 | 31.4 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 13.7 | 15.4 | 17.3 | 19.0 |

Official | 14.7 | 12.8 | 10.9 | 12.9 | 13.7 | 12.2 | 12.7 | - | - |

Sub-Saharan Africa | |||||||||

FDI | 4.3 | 4.3 | 8.1 | 6.5 | 8.1 | 6.1 | 13.8 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

Loans | 7.6 | 3.2 | 4.5 | -1.4 | -0.9 | -0.9 | -1.0 | 0.2 | -0.5 |

Private | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 6.4 | 10.0 | 12.2 | 11.1 | 9.9 | 12.0 |

Official | 17.8 | 15.0 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 12.7 | - | - |

Source: World Bank, Global Development Finance (2004), pp. 181-186, 200. The tables combine the IMF's current account, foreign exchange, and net inward FDI data with the World Bank's portfolio equity/debtor reporting system (DRS) data to produce an overall tabulation of how regions finance themselves externally. | |||||||||

Note: Private flows of capital recorded in this table occur in three basic forms and involve investments in equity (FDI and portfolio investments) and debt (private bank loans and multilateral "public" loans). |

The call for this new world order launched a series of epoch-defining changes in social and economic organization all over the world-changes signaled by increasing use of the term globalization to denote a trend toward economic integration and social connectedness. The major impetus and agency of these changes was a program of structural reforms (in macroeconomic policy) designed by economists at the World Bank as a means of adjusting nation-states and their economies all over the world, but particularly in the South, to the requirements of the new world order. The reform or restructuring process entailed policies of decentralization, democratization, and the downsizing of government; privatization of the means of production and economic enterprises; deregulation of product, capital, and labor markets; and the liberalization of capital (the flow of private investment) and international trade in goods and services.

Although globalization itself has been and is seen by many as both irresistible and good, it remains highly contentious in its overall impact and the neoliberal form it has taken. In fact, the policies used to advance globalization have given rise to a growing antiglobalization movement, a movement opposed less to globalization per se than to its neoliberal form. The reason for this opposition is clear enough. Neoliberal globalization has led to sharp increases in what the United Nations has termed the inequality predicament: yawning and growing inequalities in access to productive resources and the distribution of wealth and income. Just one expression of this income gap and its associated global divide is the fact that after two decades of neoliberal globalization a mere 358 individuals dispose of more wealth and income than the world's poor-1.4 billion people forced to subsist on a dollar a day or less.

A growing divide in wealth and income might well be the downside of globalization. There is a presumed upside, however, in the growth and dynamics of free trade. The theory is that if all national governments were to abolish their restrictions on the movement of capital and trade in goods and services the result would be an enormous expansion of world production, "lifting all boats" in the process. Nevertheless, the practice of many, if not most, governments lags considerably behind this theory. Notwithstanding the advances made in the liberalization agenda vis-Ã -vis finance (the flow of capital) and trade over the past two decades, and despite the efforts of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in this regard, world trade today is far from free, and it certainly is not fair. In fact, the governments that have most vociferously pushed the free trade agenda-the European Union, the United States, Canada, and Japan-have been most reluctant to drop their import duties and other trade barriers in sectors, such as agriculture, where their domestic producers would undoubtedly not survive the pressures of free global competition. The end result of the diverse conflicting pressures of free and controlled trade is a trend towards regionalization rather than globalization, a trend reflected in the formation of diverse regional free trade agreements and associations of countries committed to free trade within a regional zone of the world economy. Such agreements and associations include the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed by the governments of Canada, the United States, and Mexico in 1994. A more recent Free Trade Agreement for the Americas, pushed by the U.S. government, could not be concluded because of irreconcilable differences between the United States and Canada on the one hand, and some countries like Brazil on the other, as well as widespread opposition from civil society organizations in Latin America. On the South American continent, two regional free trade associations were successfully formed, Mercosur in the Southern Cone of South America and the Andean Pact in the Andean highland region. Similar regional associations have been formed in the Caribbean (CARICOM), in Southeast Asia (ASEAN), and West and Southern Africa (ECOWAS, SADC). Of course, in Europe an initial free trade agreement has morphed into a "community" of nations sharing a common currency and governance structure as well as free trade.

Critical Commentary and Future Directions

Globalization and regionalization can be viewed either as conflicting or as complementary processes. On one hand, regionalism is seen by many as a springboard for a more effective participation by regionally located firms in the global economy. On the other hand is the argument that regionalism can serve as a bulwark against globalization, a mechanism for preserving regional autonomy, identity, and values. Such a view is perhaps most clearly evident in Western Europe but can also be found elsewhere; thus Fagundes Vizentini describes Mercosur as a regional body intended to provide an alternative to economic integration with the United States and global economies, while Walden Bello argues that ASEAN could be transformed into a regional body that offers an alternative to neoliberal globalization.

There is a more general observation about regionalism, namely that it has a chameleon-like ability to be used for different purposes. Regionalism can be, and historically has been, used to either integrate with or provide insulation from the international economy. Thus, it is not surprising to find that regionalism is being advocated in both ways in the current phase of world development and globalization. It is not simply a question of whether regionalism is complementary to or competitive with globalization, but of which model is dominant in any particular region and the role of capital flows in the process. The struggle for market share and domination is being fought across the world, with the forces of capital mobility and economic integration currently in the ascendancy. This battle for the world market is not only being fought regionally but has resulted in an as-yet-unsettled debate on the connections between capital flows and regionalism.

�

References

Antoniades, A. (2007). Negotiating the possible: A perspective from Western Europe. In Paul Bowles, ed. & Henry Veltmeyer (Eds.), What is globalization?: Vol. 2. Critical regional perspectives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Bello, W. (2007). A rollercoaster ride: A perspective from Southeast Asia. In Paul Bowles, ed. & Henry Veltmeyer (Eds.), What is globalization?: Vol. 2. Critical regional perspectives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Breslin, S., ed. , Hughes, C. W., ed. , Phillips, N., ed. , & Rosamond, B. (Eds.). (2002). New regionalisms in the global political economy. London: Routledge.

Helleiner, E. (2007). A rhetorical weapon? A North American perspective. In Paul Bowles, ed. & Henry Veltmeyer (Eds.), What is globalization?: Vol. 2. Critical regional perspectives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Tabb, W. K. (2004). Economic governance in the age of globalization. New York: Columbia University Press.

Vizentini, Fagundes. (2007). The crisis of neoliberal globalization: A perspective from South America. In Paul Bowles, ed. & Henry Veltmeyer (Eds.), What is globalization?: Vol. 2. Critical regional perspectives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2003). World investment report 2003: FDI policies for development-national and international perspectives. New York: United Nations.

World Bank. (2004). Global development finance. Washington, DC: Author.