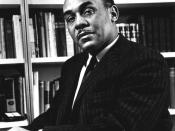

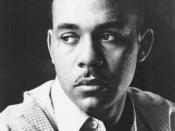

Seeds of Rebellion In the first chapter of Ralph Ellison's novel, "Invisible Man,"ÃÂ the author relates to the reader how experiences and education can transform the meekest of conformists to an unlikely rebel. Ellison subtly hints at the seeds of this progression through anecdotes that his narrator will later be able to examine and comprehend once he is enlightened while attending college. Painted against the backdrop of a pre-civil rights south, we are given the picture of a man at odds with his place in a segregated society.

The chapter opens with a reference to the narrators grandfather, who upon his deathbed, intones upon his family to "keep up the good fight"ÃÂ (Ellison, 2359). For all his days, the grandfather had been a complacent ex-slave conforming to the white supremacy way of life. By working hard and staying "in their place,"ÃÂ (Ellison, 2359), blacks of that era were ensured their survival by staying out of the white man's ire.

The narrator's grandfather's fierce change of heart however, coupled with his last words to "learn it to the younguns"ÃÂ (Ellison, 2360), begins the first trace of rebellion in the conformist mind.

The safety, which came along with being "invisible,"ÃÂ is at first important to the narrator. He too, like his grandfather before him, had conformed to the ideals and expectations that the white majority thought a black at that time should imbue. Through his childhood, the narrator's passivity was accompanied by strong pangs of guilt due to the curse of his grandfather's last words. Being "praised by the most lily-white men"ÃÂ (Ellison, 2360) conjured thoughts of himself as a traitor to his grandfather and his race.

By choosing to give a speech to his high school class, the topic of humility as the black key to progress, is another example of his conformity. This earns him the opportunity to give his oration to a meeting of the town's leading white citizens. Naively assuming that he would at last be accepted as an equal, reading his agenda in front of a dignified audience of white lawyers, teachers and even a "more fashion-able pastor"ÃÂ (Ellison, 2361).

Upon arriving, his individuality is taken, as he becomes one of a group of black boys forced into a gladiatorial "battle royal"ÃÂ event. Ellison again shows his narrator's conformity by allowing him to concede to the wishes of the whites. With luck and a little deception, Ellison's narrator becomes one of only two boys left in the ring. Here we see a small rebellion as the narrator allows the blindfold, which had previously kept him at a disadvantage during the fight, to become askew thus providing him with the much-needed vision to his opponent's blindness.

Wanting desperately to give his speech, Ellison's narrator once again attempts conformity by suggesting to his fellow black combatant that he take a dive to end the fight. Even the promise of the prize money and more compensation does not spare the narrator from being knocked out. Prior to the speech, the black fighters are subjected to further humiliation, by being coerced onto an electrified rug to receive their prize money. Dazed, shocked, and his mouth filling with blood the narrator is now allowed to give his speech, during which we see the most telling foreshadowing of a change toward the rebel. Amid the catcalls and derisive laughter the narrator subconsciously slips on a phrase that was "often seen denounced in newspapers at the time"ÃÂ (Ellison, 2368): Social equality. Consequently, in Ellison's narrator we have glimpses of both the rebel and the conformist, a protagonist who is fighting both himself and society over his conformity.