Cielo Fortin-CamachoKatrina BormanisApril 12th 2007ARTH 360 Aspects/History of PrintThe Sleep of Reason Produces MonstersÃÂThey are so subtle that people with the sharpest intelligence do no usually at first comprehend all the moral meaning of some, and those with little perspicacity need time and help to understand them ÃÂ-Gregorio Gonzalez Azaola, ÃÂSatiras de Goya,ÃÂ 1811Dreams are defined as ÃÂa series of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that occur involuntary in the mind during certain stages of sleepÃÂ(Websters). Often they are a wild fantasy or hope and more so an abstraction of the mind. Frequently dreams are said to portray events and images that are highly unlikely to occur in physical reality. The exception to this scenario is something known as a lucid dream. In these dreams, the dreamer themselves realizes that they are indeed dreaming and are sometimes capable of changing the feel and plotline of the story their mind is producing.

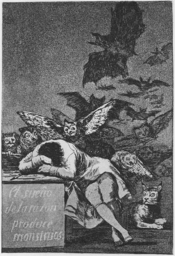

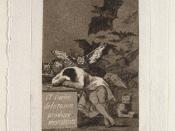

In lucid dreams the suspense is quickly damaged but emotions are often heightened. People can often find inspiration from dreams, whether they are goals they wish to achieve or changes in their life they long to make, in either case there is always something that can be drawn from dreams. In GoyasÃÂ supposal autobiographical portrayal in his print entitled El Sueno de la Razon Produce Monstruos (translates to The Sleep [or dream] of Reason Produces Monsters), he expresses a rare yet common type of dream commonly referred to as a nightmare. Nightmares consist of the same traits and qualities of regular and more common dreams but are filled with frightening thoughts, feelings, and/or images. In this print Goya expresses his fears of the society surrounding him he feels is unwilling to change for the better (Tomlinson, 3) Goya mockingly expresses his fears by perhaps portraying the society as the demonized bats, owls and the craze eyed finx that linger and swarm behind him. Although it may seem clear to some, I feel as though GoyasÃÂ satirical form of expressing his thoughts and emotions leave a lot of room for imagination when interpreting this print.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters was produced in 1799 as part of an eighty piece print series known as Los Caprichos. These fantasy type etchings and aquatints portray the vices of contemporary Spanish society including what he considered to be quack doctors, foolish aristocrats, greedy monks and predatory prostitutes all became victim of ridicule. Each tiny detail of his eighty etchings was destined to vex, insult and wound. The moralizing nature of Los Caprichos is emphasized by their mode of presentation in a bound and numbered series accompanied by individual captions, a format traditionally used for moralistic embles (Tomlinson, 6). The publication in 1799 of Los Caprichos marked the end of the Enlightment, the Age of Reason. The prints themselves marked the inspiring peak of a longer Renaissance tradition, that sustained European art for nearly four centuries.

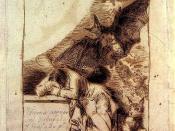

To better understand Francisco Goyas discontent with his home country of SpainÃÂs government it is necessary to understand the events that might have triggered his fury with his homelands society and government. Beginning in 1788 Spain was taken over by the second son of Charles III, King Charles IV. Contrary to his father, Charles IV proved to be a very ineffective leader, so much so that in 1792 he virtually surrendered the government and its power to Godoy, a Spanish statesman and ally of Napoleon I, his chief minister and the favorite of his wife, Maria Luisa. In 1793 Spain entered into the French Revolutionary Wars but turned around in 1795 to make peace with France in the second Treaty of Basel. Spain was again entering war in 1796 when with the Treaty of Jan Ildefonso Spain allied itself with France and became involved in the war with England. In 1797 Spain suffered major naval defeats at Cape St. Vincent and in 1805 at Trafalgar. Things did not look up after the making of Los Caprichos in 1799; in fact, the convention of Fontainebleau (1807) precipitated the events leading to the Peninsular War. As French troops marched on Madrid in March of 1808, a popular uprising led to a coup at Aranjuez; the king was forced to abdicate in favor of his son, Ferdinand VII. Napoleon I fooled both father and son into a meeting with him at Bayonne, France, and forced them to give up in turn. The royal family was held captive in France until 1814, while Joseph Bonaparte was king of Spain. Charles IV and his family were unfavorably portrayed by Goya, who was one of their court painters (Tomlinson, 42)Minor disagreements between historians arise regarding the date of when Goya began the making of Los Caprichos. Although brought out for the public in 1799 it is clear the set was started years prior but the exact date however, remains a mystery. Fred Licht's book Goya, says Goya began laboring on this set in 1797; Reva Wolf's book Goya and the Satirical Print says he was laboring on it in 1796; Xavier de Salas' Goya quotes two sources showing that Goya began preparing the Caprichos in 1793 (Hofman, 124). It is though relatively certain that The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters was finished or that preliminary drawings were done in the year 1797 and inscribed ÃÂThe author dreaming. His one intention is to banish harmful beliefs commonly held and with this work of Caprichos to perpetuate the solid testimony of truth.ÃÂ GoyaÃÂs intention in making Los Caprichos is concisely stated in the inscription of the preliminary drawing for plate forty-three, it reads as follows:ÃÂThe artist dreamingÃÂ solid testimony of truth.ÃÂ In which he explained further in the publication announcement of the Caprichos to years later in 1799 in which he saysÃÂSince the artist in convinced that the censure of human errors and vices (though they may seem to be the province of the eloquence and poetry) may also be the object of painting, he has chosen as subjects adequate for this work from the multitude of follies and blunders common in every civil society, as well as from the vulgar prejudice and lies authorized by custom ignorance or interest, those that he has thought most suitable matter for ridicule as well as for exercising the artificers fancyÃÂ ÃÂ (Steadman, 42)The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters was originally created as the front piece for the series but was later pushed back to plate forty-three and replaced by a less outspoken plate, the Autorretrato de Goya, a self portrait of Francisco himself at the age of fifty-five, where prominent imprints of years, struggle and sickness show. The sketchbook was not put together as a unit; in fact, the plates were only numbered and put together many years after GoyaÃÂs death. It was then that the most gruesome and controversial plates were put towards the back a ÃÂsecondÃÂ chapter of Los Caprichos . It is said that these plates can be shuffled around such as playing cards but regardless they will never come together as a coherent whole. There is only one continuous sequence of plates in Los Caprichos, plates thirty-seven through forty-two show animals portraying human fools in satires of education, arts, nobility and doctors. With this is mind we are obligated to consistently accept the creatorsÃÂ sudden changes in perspective. (Hofmann, 73)The Sleep of Reason is thought to be the first plate in a second chapter of Los Caprichos, a more dreary plate where evil takes form in a crouching lynx and menacing birds of prey. It was thought, however, that Goya was actually working on two series of etching projects simultaneously, one of a dream sequence of which The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters was the front piece, the other a series of more general satires, but ultimately merged the two projects in to one series (Steadman, 31).This emblematic self-portrait conceals and portrays the artist. He encodes his stance and position on where he stands but hints at the dangers of that the creative is party to. (Hofmann, 85) Goya proclaimed there were no longer rules in painting, and although many opposed, this became his driving force behind the ÃÂridiculous, false, improbable and exotic objects, of such kind as the grotesques.ÃÂ (Hofmann, 123) One early reviewer even saw the series as a satire of superstition, repressive religion, idleness, and ignorance (Tomlinson, 11). Goya said the following of this divisive print: ÃÂFantasy, having been abandoned by reason, brings forth impossible monsters. Combined with reason, it is the mother of the arts and the origin of wonders.ÃÂ It was with this and a claim that his Caprichos should be ranked on the level of ideal concepts synthesis that set himself up for a lot of opposition. For Goya truth and beauty were no longer congruent and truth was found where others could only see grotesque and exotic fancies (Tomlinson, 13)So where did the truth lie in The Sleep of Reason? Dreams are argued to be your inner truths manner of expression.

ÃÂThat is what happens to all of us when we dream, and who will draw the borderline between waking and dreaming? Just as not everyone dreams who sleeps, not everyone sleeps who dreams,ÃÂ-Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Uber Physiognomik wider die PhysiognomenAs mentioned prior, plate forty-three falls almost exactly in the middle making it a turning point in the preceedings. We see a man with his head rested on his arms, as though sleeping, making this a passive attack, seated at what the various tools indicate this to be the work table of an ingraver. Bats and owls attack him and to his right a lynx waits for his move. In first glance it all seems very clear, that is, until the inscription is translated from Spanish. Keeping in mind that sueno is Spanish and can be directly translated to mean sleep or dream. Generally the double meaning of this word has been ignored by scholars. The expression ÃÂproduce monstruosÃÂ can be translated to have two meanings-one passive and one active. On the one hand it addresses the nightmare overcoming the dreamer, but on the other can suggest his mastery of it through the act of creation. (Hofman, 132)There is a religious enlightment you could say found within this print. Perhaps, the artist himself takes the role of priest, the etching needle and pencil take place as the cross, and the print itself represents the religious message. It is under the Catholic influence that we allow sins if they are recognized and repented. Goya here in Los Caprichos gathers a range of sins including, wrath, avarice, envy, gluttony, pride, sloth and lechery and make this and evil collective dream in which backs are turned on everyone. And so it is here the artist can exorcize the demons by giving them form. He seizes control of evil forces by transforming them to demons and considering the ÃÂmythical fear.ÃÂ(Hofmann, 135)All together, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, could easily be called Francisco GoyaÃÂs most recognized print. No artist of the past speaks more directly to our generation than Francisco Goya. With famine, pestilence, violence and war sharply in our eyes, his prints and the deeply sympathetic view he takes of these subjects claim the vivid attention of an informed modern audience (Tomlinson, XI). It is their universal appeal that granted Los Caprichos GoyaÃÂs most popular work. Although clearly not the case when they were first published, selling a sheer twenty seven out of two-hundred and forty. In 1803 Goya did manage to sell the remaining two-hundred and seven-teen copies to the king, therefore recovering some of his cost for the project. The irony of this disastrous failure is that it was primarily through Los Caprichos that Goya was recognized outside of Spain. Domenico Tiepolo, for example, owned a set of Los Caprichos before his death in 1804 as did French romantic painter, Eugene Delacroix, who even borrowed freely from GoyaÃÂs image (Tomlinson, 44)Pablo Picasso once described Francisco Goya as the most successful artist in poetically combining art with politics. Goya created what he described as a "universal language" that "would encourage men and women to reflect on the world and their roles and actions within it". He wanted to provoke deeper thought on the fundamental problems of the revolutionary epoch in which he lived. The album drawings are his personal reflections, and proves that a nations revolutionary thinking does not have to interfere with an artistsÃÂ individuality or stunt their creative thought and it allowed Goya to produce images that impacted the art world ad society for generations to come.

Azaola, Gregorio G. Satiras de Goya. Trans. Enriqueta Harris. Burlington: BurlingtonMagazine, 1964.

"Dream." Def. 1a. Websters 9th New Collegiate. Ed. Frederick C Mish. 9th ed.

Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam/Webster Inc, 1987.

Hofmann, Werner. Goya. Trans. David H Wilson. High Holborn: Thames & Hudson,2003.

Tomlinson, James A. Graphic Evolutions: The Print Series of Francisco Goya. New YorkCity: Columbia University Press, 1989.