Star-Spangled Spaghetti and Meatballs:Italy, Identification, and the International Struggle over Genre Ownership.

When one envisions all of the magnificent sights Italy has to behold, many images might spring to mind, such as Roman coliseums, a gondola peacefully cruising the canals of Venice, or numerous scenes from Sparticus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960) . With all of this historic grandeur, one may question the reasoning behind the infatuation much of the world had with one of Italy's odder phenomenon's, "The Spaghetti Western", a style of film making which has little basis in the more "literal" historical assumptions about Italy's culture. On the many busts of Caesar which adorn Rome, and beyond, nary a Stetson hat is to be found, and one can imagine that Michelangelo's masterpiece "David" would have been a very different vision of a man if he were wearing spurs. Yet amidst all of these contradictions, lies one of Italy's more complex art forms.

Among all of this post-war confusion which reshaped much of Italian culture as the country attempted to redefine itself in the wake of Fascism, "The Spaghetti Western" represented a filmic revaluation of the past in an attempt to define the new face of Italy as strong and distinct. "The Spaghetti Western" was so quintessentially Italian, because it provided a unique insight into the mindset of a culture in transition, bridging the gap between the neo-realistic form of Italian filmmaking, and a that which provided a revisionist historical revaluation of the post-war struggles of the "common" Italian.

Because of its easily identifiable characteristics The Western genre served as the ideal venue for the presentation of many of the challenges encountered by Italy as it strived to reach its goal of a contemporary identity. In the middle of shootouts in town squares, the building of railroads, and gangs of outlaws on horseback, these films contained a complex examination of such milestones in the post-war identity of Italy, as the downfall of Fascism, the rural exodus, and the trials and tribulations encountered among the mirage of prosperity known as the economic miracle. Considering all of these factors, it seems that there is little coincidence in the correlation between the release of the first "Spaghetti Western" and the apex of the "Golden Age of Italian Cinema". As it evolved, the "Spaghetti Western" became not only one of the most critically and commercially lauded forms of Italian filmmaking, but also that which re-defined genre mastery, and showcased the Italian people's increasing dominance over global culture, even influencing those who originally laid claim to both the historical and creative ownership of the western genre. In its essence "The Spaghetti Western" was magnificently subversive, stylistically innovative, and perhaps one the most important pre-cursors to the radical independent style of filmmaking of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

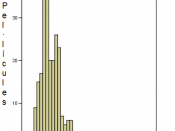

To understand the wide commercial appeal of the "Spaghetti Western" it is important to first frame the genre's emergence within the larger global cinematic context of the time period in which it was released. Fistful of Dollars, directed by Sergio Leone, is generally considered to be the first "Official" "Spaghetti Western", and first reached theatres in 1964, a symbolic year for many reasons. The mid-1960s were one of the 20th centuries' most volatile periods of transition, and this was no doubt a huge factor in relation to the international success of Fistful of Dollar's. Part of what made the film so innovative, and contributed to both its critical and financial success, was the work's ability to exist on two very distinct levels of artistic appreciation. The primary level in which Fistful of Dollars can be appreciated is attributed to the straightforward manner in which it served as an extremely effective example of a stylistically innovative form of popular entertainment. However, much of the critical success of the film, was no doubt a result of it's the rather unconventional manner in which the film dealt with conflicts over cultural identification. 1964 represented a period of decline for the traditional Western, a genre who's popularity tends to sporadically remerge in unique forms every decade or so. In 1950 it was Anthony Mann's Winchester '73 which sparked a renewed interest in this fascinating style of American mythology, and its accompanying conventions. For the next fifteen years, westerns were everywhere, filling a good portion of network Television schedules, projected on movie screens, read in comic books and even recreated by children in the family backyard. To understand the importance of the revisionist style of the "Spaghetti Westerns", one must first realize that traditional westerns were quite possibly the quintessential American genre of the 1950s, just as film noir had been in the late 1940s. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy, a moment often associated with the loss of America's post-war "Innocence", it has been suggested that there seemed to be a reduced interest in the simple morality tales presented in the classic Hollywood western. As America approached its turbulent years, with Vietnam and various forms of social rebellion in its midst, the studio system was crumbling, and more risqué international films were gaining both critical and commercial prominence. As classics like Tom Jones (Tony Richardson, 1963) and Frederico Fellini's 8 ý (1963), won Oscars, and even managed to take home a respectable percentage of box office tallies, there evolved an increasing acceptance of overt sexuality and violence in cinema. Combine this decreased ethnocentrism, and the downfall of the production code with the American people's love/hate relationship with the western film, and it becomes evident how 1964 provided an ideal cultural climate for the debut of a unique forum which depicted the struggles of the Italian people, without alienating audiences in the North America.

The political environment of Italy in 1964 was a no less influential contributor to the success of the "Spaghetti Western". Almost twenty years after the downfall of fascism, Italy was still struggling to rebuild its image in hopes of reaching a post-war ideal. These two decades represented a period of change so drastic, that the majority of films made during these years seemed to have the primary goal of helping Italians comprehend a situation which was unlike any they had experienced before. One of the reasons why Italian films are so highly regarded today is because of their unique depiction of the hardship encountered during this unusually difficult period in Italian history, functioning as seemingly truthful documents of a societies' quest for identity. As Italians experienced post-war unemployment and poverty, so did the protagonists in such stark neo-realist films as The Bicycle Thief (Vittorio De Sica, 1948) and Umberto D (Vittorio De Sica, 1952), and as the economic miracle of the mid-1950s reached its pinnacle, the rural exodus, and the seemingly unmanageable expansion of urban areas, was depicted with equal realism in classics like Accatone (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1961) La Notte (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961). As the mid-1960s approached, neo-realism tended to be abandoned often in favour of a zanier sexually infused style of Italian comedy, referred to as Commedia Dell' Italiano. This fascinating style still allowed for the exploration of the misgivings encountered among Italians in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but in a much less depressing manner when compared to other more typically realist films, instead choosing instead to opt for a more humorous and distinctly Italian outlook on the events of the previous two decades. This style was first greeted with international success during the release of Big Deal on Madonna Street. (Mario Monicelli, 1958), and this film would serve as a blueprint for the future presentation of the struggles of the Italian people, as showcased within the context of an easily accessible Hollywood genre, in this particular instance the chosen genre context was that of a heist film.

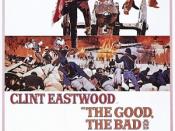

Big Deal on Madonna is often cited as the seed from which the "Golden Age of Italian Cinema" grew, this was a period in filmmaking history which oddly mirrored the perceived downfall of "Classic Hollywood Cinema". This fascinating era reflected a certain pride on the part of Italians as they finally defined an identity for themselves as a colourful culture whose ancient traditions have intermingled with their contemporary post-war situation to create an attempt at mass assimilation, as the rural exodus led to the intermingling of various ethnic groups within the country. This process had a huge impact on the creation Italian sense of self, after twenty years an identity was finally being forged, and Italians were eager to share it with the world. Perhaps the most important landmark in Italian cinema prior to the release of the "Spaghetti Western" was the international acclaim for the celebrated early 1960s works of Frederico Fellini, which included such revered films as La Dolce Vita (1960), and 8 ý (1963), anti-realist works which showcased the new Italian urban male, in a world on the cusp of sexual liberation. With these positive reception of these works, Italy became one of the swinging capitals of the new Europe, and as their own cultural supremacy crumbled, the western world was eager to embrace this exciting transition in popular culture. With Clint Eastwood as its star, and Sergio Leone at its helm, Fistful of Dollars, served as yet another invitation for the western world to experience the increasingly popular visions presented by European cinema, one which's genre conventions and star allowed for easy accessibility, with seemingly few artistic pretensions implied, but with many in existence. In a period of increased self-awareness, "The Spaghetti Western" was one of the first popular forums in which Italians could begin to revaluate their past, in hopes of creating a prosperous future.

For all of the talk of Sergio Leone as an "auteur", there seems to be much confusion over the artistic origins of his work. When asked about the creative aspirations which led to the birth of Fistful of Dollars, Leone responded that his first "Spaghetti Western" merely aspired to be "An historic break with the conventions of the genreâ¦I introduced a hero who was negative, dirty, who looked like a human being, and who was totally at home with the violence that surrounded him"1Leone's goal as a filmmaker was to create an artistic discourse, through an element of the unexpected "On first viewing, people experience the aggression of the images. They like what they see without necessarily understanding everything. And the sheer abundance of baroque images privileges surprise over comprehension. On second viewing the grasp more fully the discourse which underlines the images"2Sergio Leon is rarely put into the same category as neo-realist filmmakers such as De Sica, Rosselini, or Passolini, although his films often employ similar thematic elements and techniques. One of Leone's more celebrated stylistic flourishes were his extreme close-up shots of actor's faces, as Clint Eastwood noted "Sergio believed, as Fellini did, as a lot of directors do, that the face mean everything, you'd rather have a great face then a great actor in a lot of cases, Certain characters in his films, the bad ones in particular, are very Italian, and even very Roman."3Although the Leone "Spaghetti Western", and other similar films are often more closely associated with Hollywood styles of filmmaking, there is no denying that the genre is greatly in-debt to several Italian influences. Never having lived in the United States, Leone's films were merely imaginary interpretations of America, often derived from his life-long relationship with cinema. Pauline Kael called Leone's style of filmmaking "Dream Playsâ¦his movies are visions sustained from childhood of Hollywood's version of America"4. When questioned about the influence his own culture had upon his artistic interpretation of America, Leone did not deny that his Italian lineage was vital to the structure of his films stating that "Obviously there is a culture behind me I just can't wish away."4By being aware of the Italian cultural influences which permeate Leone's works, it becomes apparent that Leone's understanding of cinematic conventions from an outsider's perspective, lends itself most effectively to the creation of revisionist ideology. Because Leone's films were so influential, this ideology can be witnessed even in several films which Leone himself did not direct, but which are no less ideological in their examination of post-war Italian culture within the context of quasi-American genre. Thanks mostly to the popularity of the "Man with no Name" Trilogy, "Spaghetti Westerns" adopted several conventions which all seem to be rooted in Italian post-war insecurities. The majority of "Spaghetti Westerns" tend to feature a protagonist who is portrayed by a "Hollywood" actor, beginning with Fistful of Dollars, there arose a tradition in this genre to have this amoral American, serve as liberator to the characters portrayed by Italian cast members, who in the context of these films, were often being marginalized by their fellow country man. The Italian actors featured in these works were rarely overtly exposed as being Italian during the course of the filmic discourse, but the "outsider" protagonist almost always served as a diametric opposite to said Italians in the cast. This element alone seems to prove that "The Spaghetti Western" is a revaluation of Italian culture, through a western ideology. The concept of an American liberating Italians from corruption is not entirely be attributed to fiction, especially considering the events of the second world war. Often in this genre, the shift in the power structure of their town, which mirrors that of post-war Italy, leaving the community in even greater sense of disarray, due mostly in part to the influence the "Ugly American" who always seems to be trying to settle a vendetta, or just functioning in his own best interest. The amoral protagonists of the "Spaghetti Western" are representative of new form of corruption, being of little benefit the Italians in the film. This portion of these films tends to mirror the pre-economic miracle, post-war period in which the original perpetrator of corruption appears to be eradicated, yet the greed of those who currently hold power, marginalizes the common Italian, as represented by the non-Hollywood actors in the film. Often these films also deal with insecurities quite similar to those encountered during the period of the economic miracle and the rural exodus, when Italians migrated on mass from the countryside to urban areas in search of employment during a period when Italy's economy was booming between the mid 1950s and the early 1960s, with many only ending up worse off then during the post-war depression period in the late 1940s. This anxiety is often expressed through the usage of trains, and the concept of "The Other" as having unknown origins, with more important places to go, and with more important tasks to complete once he settles his vendettas. Trains in relation to the economic miracle and the rural exodus were used most effectively in Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968) in which the villain is portrayed by one of the most ideally American actors of all time, Henry Fonda, playing the role of a corrupt Railroad employee, Frank, who is willing to murder innocent families, and destroy their farms in order to expand his company's train coverage, eradicating rural communities in favour of big business. In this particular instance, the "Evil American" was destroyed not by members of the rural, predominantly Italian community, but rather by another American, Harmonica, portrayed by Charles Bronson who is the brother of Frank, and seems to act only out of revenge. In many "Spaghetti Westerns" there seems to be an association between greed and Americans. According to Loren Quiring's essay on consumption in western films "For Leone, what drives America forward is still the mechanical gnashing of teeth, a commerce of masculine agents gunning for money and statusâ¦To be a self-made American, either as a hero or a villain, one remake the world into a consumable object". The American influence on these innocent Italians is both idolized and feared, perhaps functioning as an allegory for the effects of the economic miracle, which created a demand for the mass-consumption of consumer goods, yet which also led many to question the reasoning for the desire for such objects. The content of many "Spaghetti Westerns" suggests an unconscious hostility on the part of Italians who feel as if they have traded one dictatorship for another, the later being a subversive attempt on the part of big business to create the illusion of comfort, only to manipulate them into being agents of consumption.

Although there is often a tendency to revert back to reviewing the films of Sergio Leone when analyzing "Spaghetti Westerns", many of the films created by his cohorts, offer an equally fascinating examination of post-war Italian ideology. One of the finest examples of a complex interpretation of the post-war Italian value system can be examined in the rarely mentioned Days of Wrath (Tonino Valerii, 1968), a brilliant allegorical representation of the feelings of betrayal felt among many of those who fought so hard to overthrow the fascist regime, only to be taken advantage of by a seemingly heroic, but in reality abusive, manipulative, and selfish American influence. Like all "Spaghetti Westerns" this film creates the illusion that it is set somewhere in the old west, yet the boundaries between American and Italian are once again very clearly defined, even if not specifically stated. Central to the plot of Days of Wrath, is the relationship between Talby, and Scott Mary. Like all of the classic "Spaghetti Western" the outsider, Talby (Lee Van Cleef) prefers to be called only by one name, or by no name at all, as he rides through town wearing the finest in tailored clothing. Young Scott Mary (Giuliano Gemma), is the old west equivalent of the Bicycle Thief's Antonio, albeit younger. Scott, like Antonio Ricci, is impoverished and in search of a manner in which to improve his economic status. In Talby, Scott Mary sees respect, and power, all derived from the fear of Talby's fast draw. When Scott Mary first encounters Talby, he introduces himself merely as Scott, and Talby asks him if he has a last name, almost out of fear caused by the power one wields when only having a single name, being another "other". When Scott informs him that he is without a surname, Talby gives him that of Mary, and from that point on, the relationship between Scott Mary and Talby, consists of a bizarre struggle for power, based on manipulation and abuse. Days of Wrath serves as a terrific exploration of outlaw morality, as Talby claims to be teaching Scott using the outlaw rulebook, brutally beating Scott, stealing his money, and convincing him to take gunshots for him. Scott happily respects all of Talby's orders, this can only be attributed to Scott's belief in the romantic notion of the American outlaw as protector and liberator. Trusting that Talby will overthrow the corrupt power structure which infects his town, Scott follows him willing, becoming injured by a bullet in the process, and risking his life because of his trusting belief that Talby is essentially heroic, yet when the opportunity comes for Talby to become part of the corrupt power structure which he claims to despise, he quite willingly accepts it. The basis of Talby's teachings in the way of the outlaw, seem to all be derived from his own selfish thirst for power, which he justifies with lines like "I will kill anyone who comes between me and my goal", "Sometimes what done outside the law is better than what's done outside of it", "Never beg anyone, never trust anyone", and the final rule "When a man gets wounded, you got to end it". Despite these rather obvious indicators of an amoral personality, Scott, along with the audience, still believes there is a possibility that Talby will redeem himself, all because they have been lulled by the false comfort derived from the concept of the American outsider as a hero. It is not until Talby kills the only other honest character in the film, that reexamines his own concepts of morality, and shoots Talby with Doc Holliday's gun. The irony in this specific choice of weapon is quite obvious, considering that in order to destroy Talby, Scott was forced to rely on the gun of another American hero, suggesting that even in a moment of triumph, Italians are helpless without the help of an invented American hero.

It wasn't until 1973, a date significant as the beginning of a period of decline in Italian cinema, that perhaps the greatest re-evaluation of the "Spaghetti Western" occurred. The film was entitled, My Name is Nobody (Dir: Tonino Valeri) and it served as the eulogy for the traditional western, and also not so subtly suggested that the "Spaghetti Western" was soon to follow. In this film it is the Italian (Terence Hill) who functions as the heroic actant, yet on his own terms, embodying a commedia dell' Italiano sensibility, and a generosity not previously presented in the majority of "spaghetti western" heroes. At one point in the film, this character, who calls himself "Nobody", states "There are a lot of nobodies, but in truth there is only one". Serving as an almost guardian angel, Nobody, helps Jack Beauregard (Henry Fonda), a elderly gunslinger who is representative of the Hollywood western, to complete one final task which will put him in the history books before he retires. For the first time the American and the Italian, are equals, with the hero acting unselfishly, in effort to pay homage to those who influenced the current breed of gunfighter. Perhaps the most self-reflective of "Spaghetti Westerns", My name is Nobody explores the contrasts in Italian and American sensibilities, yet suggests that with one there could not be the other, at least in the context of the western. As the film concludes, and Jack Beauregard writes a letter from his boat headed to Europe, it is suggested that "Spaghetti Westerns" may portray images of Americans manipulating helpless, but in reality it is Americans who have been manipulated by Italians by allowing them to redefine their most patriotic of genres in order to reflect a completely diametrical set of beliefs. As Nobody inherits the title of the "Quintessential" western hero, Jack heads to Europe in search of redemption according to the rules of the new west, one which never existed in the first place, because by creating the illusion of an American power structure, Italy was able to subvert the mainstream and create an entirely new set of ideals, finally realizing the power and sense of identity, which for so long seemed lost amidst post-war struggles. As Jack writes Nobody in his final letter, which appropriately serves as a sort of Hollywood western swan song, as directed towards the Italians who won the metaphorical fast draw by learning how to fool Americans into a false sense of power, which like in all great "Spaghetti Westerns", leads to a bullet in the gut faster than anything else. "Preserve a little of that Illusion that made a generation tick, maybe in your own funny way, but we'll be grateful just the same, because in the end we are all just romantic fools."End Notes1.Frayling, Christopher. "The Making of Sergio Leone's Fistful of Dollars" Cineaste 25:3 (Summer 2000) 14-22.

2.Frayling, Christopher. "The Making of Sergio Leone's Fistful of Dollars" Cineaste 25:3 (Summer 2000) 14-22.

3.Frayling, Christopher. "The Making of Sergio Leone's Fistful of Dollars" Cineaste 25:3 (Summer 2000) 14-22.

4.Quart, Leonard. "I Still Love Going to the Movies: An Interview with Pauline Kael" Cineaste 25:2 (March 2000) 8-135.Quiring, Loren. "Dead Men Walking: Comsumption and Agency in the Western" Film & History 33:1 (2003) 41-46Works CitedBooksFrayling, Christopher Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 1981.

Mitchell, Lee Clark Westerns: Making the Man in Fiction and FilmChicago : University of Chicago Press. 1996.

Journal ArticlesFrayling, Christopher. "The Making of Sergio Leone's Fistful of Dollars" Cineaste 25:3 (Summer 2000) 14-22.

Quart, Leonard. "I Still Love Going to the Movies: An Interview with Pauline Kael" Cineaste 25:2 (March 2000) 8-13Quiring, Loren. "Dead Men Walking: Comsumption and Agency in the Western" Film & History 33:1 (2003) 41-46

![[Forum Boario, Rome, Italy] (LOC)](https://s.writework.com/uploads/17/171586/forum-boario-rome-italy-loc-thumb.jpg)