Troi Irons

Hist 202B

Professor Endy

1-29-07

Coney Island: The Prozac of the Early 20th Century

Immigrants, factory workers, and middle to upper class citizens alike, needed breaks from the burdens of their daily lives. The immigrants and factory workers needed a recess from their strenuous jobs and poverty-stricken lives, while the better off individuals needed a vacation from the demands of the structures of society. Coney Island became this universal Prozac by which people could forget their troubles "in the intense sensations of the moment". (Kasson, 81)

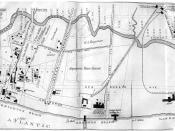

Coney Island began in 1829, as a mere "seaside seclusion" for wealthy people. It had the usual utilities, such as restaurants, saloons, and even a steamboat (Kasson, 29), and the added "rougher element" made it the beginning of a perfectly normal getaway. However, as time passed on, it would become one of the most memorable amusement parks in history.

The first thing worth noticing is that it was called an amusement park, not just a park, or an exposition.

In contrast to the White City and Central Park, Coney "sought frankly to entertain rather than to uplift" (Kasson, 27). This methodology appears to have worked: Frederick Olmsted, a man instrumental in developing Central Park, was quoted as saying the following about the White City. "Expression of the crowd too business like, common, dull, anxious, and care-worn" (Kasson, 23). Conversely, lower class citizens and immigrants, who could not afford anything at Coney Island, still came to the park, "merely for the joy of mixing", "the sense of humanity", and the "good humor" that was always present in the ambience (Kasson, 39).

For immigrants and factory workers, the amusement park was an escape from the "loneliness, separation from the community", and "despair" they felt as a result of their poverty (Industrialization, 85). They felt a "sense of degradation" that Coney could dispel (Industrialization, 85). Coney Island let people forget the outside world and condensed all the social classes into one class by providing different forms of entertainments that could reach out to all varieties of people and different cultures (Kasson, 39-40).

This variety included the upper class citizens. For them, the amusement park "tested accustomed social roles", and "mocked established social order" (Kasson, 50). By doing so, it freed them from the shackles of the structured society, and the "naughtiness of violating customary proprieties" (Kasson, 47) and succumbing to those "violent, dangerous pleasures" (Kasson, 88) fascinated them. In the outside industrial world, the members of the middle and upper class were required to behave a certain way, wear specific kinds of clothes, and work in a certain job field. Coney Island was a different "dream" world "where all is bizarre and fantastic" and "gayer and more different from the every-day world" (Kasson, 69). It was completely free from the laws of society, and allowed even the wealthier citizens, in addition to anyone else who visited, to be free for a day, or however long they chose to stay at Coney Island.

However, this universal Prozac was bound to have some side effects. Coney Island was a magnet for gamblers, whores, and con men (Kasson, 29). In addition to harboring these unpleasantries, the amusement park contributed to a gradual rise in tolerance of lewdness. Postcards, photographs, and even rides captured this increasing permissiveness. There was even one ride called the "Cannon Coaster" that advertised with "Will she throw her arms around your neck and yell? Well, I guess yes" (Kasson, 43).

Many of the critics played out these downsides in their arguments against the amusement park. Yet, these critics were rich "ministers, educators, and reformers" who became the leaders of the genteel culture (Kasson, 4). Being wealthier than their neighbors were, the rich believed themselves to be "the mere trustee and agent for [their] poorer brethren" (Industrialization, 77). Thus, a world where the immigrants and lower class citizens could escape from the wisdom and overflowing knowledge of their superiors was an outrage. Some may have had altruistic motives, but the majority probably did not. They argued that Coney Island promoted promiscuity, lesser morals, and that it was not civil. An alternative to this mindless foolishness was the White City or Central Park. It was reported that once in Central Park, "rude, noisy fellows, as they entered the park, became hushed, moderate, and careful" (Kasson, 15). There, the ambience was uplifting and one could be social, have fun, and still be restricted to the rules that the wealthy thought to be suitable.

Regardless of their wishes, millions of people continued to crowd into Coney Island until the late 1910's and early 1920's when fires destroyed the amusement parks, and the owners either died, retired, or became bankrupt and out of business (Kasson, 111-112). As to a further explanation for the decline in attendance to the amusement parks, one man says, "The radio and movies killed it. The movies killed illusions", (Kasson, 112). To elaborate on that, the adaptation phenomenon was taking place, just as in Adele Lindner's situation: as she got used to the Hellman home, she began to see the dark side. Just so, as the culture caught up to the now less daring Coney Island, the people got bored with it. Just like that, the fantastic illusion of Coney Island came to an end.

Coney Island was the Prozac for the various citizens of New York and like all medicines, had obvious side effects. The constant question was whether these side effects were acceptable or if they outweighed the advantages. I believe that Coney Island was the best possible solution for the dilemma that befell the victims of industrialization. It was an alternative for the poor to drinking the money out of their pockets like Jurgis in Oscar Handlin's The Jungle (Industrialization, 80). It mesmerized the uptight, tense middle and upper class members with its "fantastic sculptured animals" (Kasson, 65) and "enchanted garden" (Kasson, 66) lit by a quarter million lights.

Of course, a healthy balance was required between this vacation from the orderly life; the determining factors, however, are too various. Thus, this decision depends on the relative individual. An example of a good balance is Adele's coffeehouse, in which people could learn classical music on the piano and talk amongst themselves freely, in a warm environment away from the worries of work; she combined the factors of the genteel culture and the new tolerant culture. The same predicament follows us today, where the difference between the classes still increases, and we can find Coney Islands scattered throughout our environments such as modern amusement parks, or even different gadgets, like the television or the iPod. Every generation has its Coney Island and we all must, in turn, learn how not to overdose.