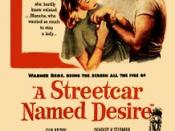

Traditionalism versus Defiance in a Streetcar Named Desire by Jonathan Rick May 28, 2000 The themes of Tennessee Williams's Streetcar Named Desire follow Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind: the emotional struggle for supremacy between two characters who sym - bolize historical forces, between fantasy and reality, between the Old South and a New South, between civilized restraint and primitive desire, between traditionalism and defiance. If Blanche DuBois represents defunct Southern values, Stanley Kowalski represents the new, urban moder - nity, and pays little heed to the past. If Stanley cannot inherit the DuBois's plantation, he is no longer interested in it. Williams's stage directions indicate that Stanley's virile, aggressive brand of masculinity is to be admired. His cruel intolerance of Blanche is a justifiable response to her lies, hypocrisy, and mockery, but his nasty streak of violence against his wife appalls even his friends. His rape of Blanche is a horrifying and destructive act, as well as a cruel betrayal of Stella.

Ultimately, however, this survivor disposes of the "paper moon" (99) Blanche, and, as we see in the closing lines of the play, he is able to comfort, with crude tumescence, Stella's weeping, as the neighborhood returns to normality.

Blanche and Stella are the last in a line of landed Southern gentry. Years of "epic forni - cations" (43), as Blanche puts it, swallowed up the material resources of the family; all that re - main are the manners and pretensions. Yet Blanche, with all her possessions in a valise, clings to her gilded, gaudy garb and imagines a world in which the values of the Old Guard, e.g., charm, wit, chivalry, and appearance?indeed, she?are still relevant. Stanley, in sharp contrast, is born of Polish immigrants; a sweat - shirted bowler and lothario, he is, as one critic has remarked, "a new breed, without breeding"?and "not the type that goes for jasmine perfume" (44). Stella, meanwhile, has renounced the worn dictates of class propriety to marry this uncouth sweetheart; she plays the placating intermediary between the poles of her husband and sister.

Since her husband, understandably, shot himself many years ago, Blanche has been avoiding reality in one way or another. In New Orleans, reality catches up to her in Stanley, who greets her brusquely. When he mentions her dead husband, Blanche becomes first confused and shaken, then ill. Later, while Blanche, as is her wont, is bathing, Stanley, imagining himself cheated of the Belle Reve plantation property, tears open Blanche's trunk looking for sale papers. Blanche demonstrates a bewildering variety of moods in this scene (two), first flirting with Stanley, then discussing the legal transactions with calm irony, and finally becoming abruptly hysterical when Stanley picks up old love letters written by her dead husband.

As the play proceeds, Blanche copes by dissimulating the problem - full Elysian Fields for "a moonlight swim at the old rock quarry" (122). Her feelings against Stanley galvanize when she sees him strike his pregnant wife in a fit of drunken rage; Stanley's feelings for her similarly harden when he overhears her belittle him as Neolithic and brutish. Blanche's imposition, her airs, and her distortions of reality infuriate Stanley, and he begins to chip away at her veneer of armor.

Williams, who was an overt homosexual in a time unreceptive to such concepts, implies that Blanche, like himself, is society's scapegoat; yet despite her neuroses, she is not a "bad per - son"?perhaps "no crazier than the average asshole out walkin' around on the streets," as McMurphy of One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest proclaims. Alas, her doomed, dandy personality is no match for the destructive, dissolute Stanley, who represents the raw animal, the prevailing dog in a dog - eat - dog world, the "one hundred percent American" (110).

As Blanche admits to Stanley and later to her fiancé Mitch, "a woman's charm is fifty percent illusion" (41), and this woman has "old - fashioned ideals" (91): she doesn't "tell the truth, [she] tell[s] what ought to be truth" (117), and prefers fantasy and shadows to the light of reality. Stanley, as her foil, is a no - nonsense, cut - to - the - chase kind of guy; he expects persons to "[l]ay . . . [their] cards on the table" (40), as if life itself was a game of seven - card stud. He is unamused by "Hollywood glamour stuff" (41), that is, the genteel lawn culture of French chitchat, social compliments, and humoring a fool and fraud like Blanche.

Thus, in one sense Blanche and her brother - in - law are trying to do outdo each other in competing for Stella; each would like to pull her beyond the reach of the other. But there is something more elemental in their opposition. They are incompatible forces, and harmony is no more than an evanescent regard for family. And yet there is a precarious sexual tension?they sleep separated by but portieres?and the mutual comprehension of the other's weakness: just as Stanley recognizes the dependence ("on the kindness of strangers" [142]) in Blanche, Blanche "ha[s] an idea [Stella] doesn't understand you [Stanley] as well as I [Blanche] do." Thus culmi - nates, amid "hot trumpets and drums," the "date" (130) (rape) to which Blanche's pomp and cir - cumstance ineluctably give rise.

Indeed, in both origin and occupation, Stanley is new blood to Blanche and Stella's blue blood. He stands on no ceremony; it is nothing for him to crush the outmoded sense of entitle - ment and superiority that Blanche personifies. That Williams has him trounce a lonely and wid - owed gadfly - gadabout, illustrates the new rules of ruthlessness and perhaps soullessness.

And yet Blanche, having watched her family estate slip through her fingers, fails to see the decadence of her patrician Belle Reve existence; Social Darwinism has replaced gentility, and this "old maid schoolteacher" (55) is really an alcoholic, nymphomaniac, parasitical casualty of the changeover. She puts on the airs of a belle who has never known indignity, but Stanley sees through her. As Eunice says, "Life has got to go on. No matter what happens, you've got to keep on going" (133).