The Pollyanna Principle is defined by Matlin (2006) with respect to memory and other cognitive processes as pleasant items are usually processed more efficiently and more accurately than less pleasant items. This was consequently named the Pollyanna Principle after the fictional character Pollyanna who was known to look on the bright side of life and to find goodness out of every environment and situation (Warr, 1971, as cited in Sargent, 2005). Numerous studies have also supported this fact by illustrating that people tend to display optimistic beliefs of themselves (Larwood & Whittaker, 1977; Svenson, 1981, as cited in Silvera, Krull & Sassler, 2002) and the external world around them (Klar & Gilda, 1997, as cited in Silvera et al., 2002).

One of the basis arising from the Pollyanna Principle contend that people are more accurate in learning and the subsequent recall of words that are found as pleasant in comparison to words that are found as less pleasant and neutral (Sargent, 2005).

Matlin and Stang (1978, as cited in Matlin, 2006) analyzed previous research of such nature and found support for this basis. This has typically been tested through the general study where subjects are tested by learning pleasant, neutral and unpleasant words and after a specified time delay they are tested on what words they can recall.

In 1979, Matlin and Gawron tested 133 students on fourteen measures of Pollyannaism to examine whether they correlated with each other. Two of these measures were self-rating and selective recall. Their results showed that students who rated themselves as optimistic and happy showed2Pollyannaism on other measures including recalling pleasant words more often than unpleasant words from a list.

A study by Lewis, Critchley, Smith and Dolan (2005) tested a related factor to the Pollyanna Principle; mood congruency. Lewis et al. tested subjects by presenting them with positive and negative words and then manipulated their affective states on recall. Functional imaging was used to monitor the subject's brain activity. Their results showed that mood congruent facilitation occurs at recall rather than that of recollection. Lewis et al results also supports the increasing evidence which already suggests that someone's affective state relates to their cognitive processes and that the person's affective state can act as a retrieval cue, for example allowing positive material and words to be more promptly recalled (Isen & Shalker, 1982, as cited in Sargent, 2005).

In 2008 Monnier and Syssau conducted a study on word pleasantness on the verbal working memory. They performed the typical Pollyanna test on thirty two psychology students and one component of their test was to ask the students, one at a time, to recall words they had previously been read. An error analysis on the results obtained on what words were recalled was carried out. Once summed Monnier and Syssau found item errors were much more frequent for the neutral and unpleasant list of words than with the more pleasant.

This present experiment (with the exception of using neutral words in the words used) was designed as a replicate of the Pollyanna Principle general study where subjects are tested by learning pleasant, neutral and unpleasant words. After a specified time delay they are tested on what words3they can recall (Matlin & Stang, 1978, as cited in Matlin 2006). It was hypothesized that a higher percent of participant's will recall more pleasant words than less pleasant words if the participants rate themselves as being in a positive mood. It was also hypothesized that if any words were recalled that were not on the word lists they would be the less pleasant words.

MethodParticipantsTen participants were chosen from the experimenter's family and friends. The participants included five females (mean age, 36.2 years), and five males (mean age, 38.8). They were all native speakers of English.

MaterialsA list of forty words was prepared as chosen by the experimenter. Twenty of these words described pleasant moods or situations and twenty described unpleasant moods or situations (see Appendix). All forty words were individually written on a card. A copy of the words was written out for the experimenter to mark on.

ProcedureThe forty cards were shuffled so they were in a random order. Each participant was tested individually and before the test began they were asked to state if they were in a relatively positive or4negative mood. Each participant was then shown a card, one at a time, and asked to try to remember them. Once the last word was shown the experimenter engaged in a two minute chat with the participant about, for example, the weather. At the end of the two minute delay the participant was asked to recall, in any order, as many words as they could. The experimenter marked off on a list of the words what words were recalled and noted if and what extra words were recalled. Once the participant could not recall any more words they were debriefed about the experiment, any questions were answered and they were thanked for their participation and time.

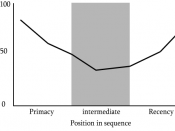

ResultsThe results of the words recalled were graphed (see Graph 1) and the variables were analyzed. All ten participants stated they were in a positive mood when asked before their test started. Overall, fifty percent of participants recalled more pleasant words than less pleasant, thirty percent of participants recalled more less pleasant words than pleasant words, and twenty percent of participants recalled the same amount of pleasant and less pleasant words. An error analysis was also conducted on the words recalled. An error was defined as recalling a word which did not appear on the cards. Word errors occurred more frequently with the unpleasant words with a mean figure of 22 compared to pleasant word errors with a mean figure of 14.

5Graph 1Number of Words Recalled by Participants.

DiscussionThe results of the current study partially supported the hypotheses; that a higher percent of participant's will recall more pleasant words than less pleasant word if had previously rated themselves in a pleasant mood. The results showed that half of the participants did recall more pleasant words than unpleasant compared to only thirty percent of participants recalling more unpleasant words than the pleasant. Twenty percent recalled the same amount of words for both6categories. The hypotheses that if any words were recalled that were not on the word lists would be the less pleasant words was also partially supported. Both two categories of words were recalled however, the results showed that unpleasant words were recalled more than the pleasant words.

The findings support the previous research completed by Matlin and Gawron (1979). The results confirmed that the current experiment did show that subjects who rated themselves in a positive mood showed Pollyannaism by recalling pleasant words more often than unpleasant from a list of words. D'Argembeu, Comblam and Van Der Linden (2003, as cited in Matlin, 2006) suggested one explanation for the Pollyanna Principle, and can extend to these current results, is that visual imagery is more vivid for pleasant events than the unpleasant events making them more readily recalled. However, the subjects who recalled more unpleasant words and the subjects who recalled the same amount of pleasant and unpleasant words had also rated themselves in a good mood. An explanation for these findings could be that the subjects selected in the current experiment were a small sample and not representative of the general population.

These results also extend and partly support the research by Lewis et al. (2005). Mood congruency was found in the subjects who recalled more words which were pleasant than unpleasant. Again, the subjects who recalled more unpleasant words and the subjects who recalled the same amount of words in both categories fail to show support for this hypothesis. The explanation for these findings could also be that the subjects selected in the current experiment were a small sample and not representative of the general population.

7The results of the current experiment showed that, of the words recalled not on the lists, the unpleasant ones were thought of more readily and this then shows support for the findings of Monnier and Syssau's (2008) research. Monnier and Syssau interpreted these findings as supporting the Pollyanna Principle and explained these results as being independent of rehearsal processing efficiency. This explanation could also be the reason for this current experiments finding.

One systematic bias observable in the results is that the pleasant and unpleasant words used are not necessarily considered to all the subjects as being pleasant or unpleasant and could have implicated which words were recalled for which subjectIn future studies on the Pollyanna Principle and to test if more pleasant or unpleasant words are recalled from a list, they could include testing more participants and also separating participants into gender and age groups. A basic reading test should also be considered completing for each participant before the start of the experiment.

In conclusion, this study examined the Pollyanna Principle and if participants recalled more pleasant or unpleasant words out of a total of forty words written on cards. The results indicated that subjects who rated themselves in positive mood showed Pollyannaism by recalling pleasant wordsmore often than the unpleasant from the list of words. However, the subjects who recalled more unpleasant words and the subjects who recalled the same amount of pleasant and unpleasant words had also rated themselves in a good mood. The results also indicated that, of the words recalled not on the lists, the unpleasant ones were thought of more readily.

8ReferencesLewis, P. A., Critchley, H. D., Smith, A.P., & Dolan, R. J. (2005). Brain mechanisms for mood congruentmemory facilitation. NeuroImage, 25, 1214-1223. Retrieved April 5, 2008, from EBSCOhost database.

Matlin, M. W. (2005). Cognition (5th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: Wiley.

Matlin, M. W., & Gawron, V. J. (1979). Individual differences in pollyannaism. Journal ofPersonality Assessment, 43, 411-412. Retrieved April 5, 2008, from EBSCOhost database.

Monnier, C., & Syssau, A. (2008). Semantic contribution to verbal short-term memory: Are pleasantwords easier to remember in serial recall and recognition? Memory & Cognition, 36, 35-42. Retrieved April 5, 2008, from EBSCOhost database.

Sargent, E. M. (2005). Does the pollyanna principle overshadow mood congruence? Retrieved April5, 2008, from http://www.anselm.edu/internet/psych/theses/2005/sargent/pollyanna.htmlSilvera, D. H., Krull, D. S., & Sassler, M. A. (2002). Typhoid pollyanna: The effect of category valenceon retrieval order of positive and negative category members. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 14(2), 227-236. Retrieved April 5, 2008, from EBSCOhost database.

9AppendixUnpleasant and Pleasant Words UsedUnpleasant wordsPleasant words1-Awful Popular2-Sick Holiday3-Bad Stunning4-UglyGood5-QuitCheerful6-MeanNice7-LonerSuccessful8-HateFun9-TerribleHappy10-EnemyRich11-PoorHope12-TerrorKiss13-LonelyFriendly14-DisgustingJoyful15-FailureBeautiful16-DeadSmile17-HorriblePleasant18-AngrySunshine19-UnpleasantLove20-LostSafeThe Effects of the Pollyanna Principle When Remembering and Recalling Pleasant and Unpleasant WordsLisa SmithStudent number: 2534873Course number: 73212