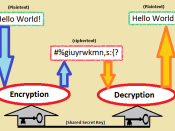

Initially, the Internet was designed to be used by government and academic users, but now it is rapidly becoming commercialized. It has on-line 'shops', even electronic 'shopping malls'. Customers, browsing at their computers, can view products, read descriptions, and sometimes even try samples. What they lack is the means to buy from their keyboard, on impulse. They could pay by credit card, transmitting the necessary data by modem; but intercepting messages on the Internet is trivially easy for a smart hacker, so sending a credit-card number in an unscrambled message is inviting trouble. It would be relatively safe to send a credit card number encrypted with a hard-to-break code. That would require either a general adoption across the internet of standard encoding protocols, or the making of prior arrangements between buyers and sellers. Both consumers and merchants could see a windfall if these problems are solved. For merchants, a secure and easily divisible supply of electronic money will motivate more Internet surfers to become on-line shoppers.

Electronic money will also make it easier for smaller businesses to achieve a level of automation already enjoyed by many large corporations whose Electronic Data Interchange heritage means streams of electronic bits now flow instead of cash in back-end financial processes. We need to resolve four key technology issues before consumers and merchants anoint electric money with the same real and perceived values as our tangible bills and coins. These four key areas are: Security, Authentication, Anonymity, and Divisibility.

Commercial R&D departments and university labs are developing measures to address security for both Internet and private-network transactions. The venerable answer to securing sensitive information, like credit-card numbers, is to encrypt the data before you send it out. MIT's Kerberos, which is named after the three-headed watchdog of Greek mythology, is one of the best-known-...