The love affair between the American public and professional sports dates back more than 100 years, to the origins of major league baseball. Although rocky at times, professional sports enjoy a special relationship between fans and their teams that has prevailed through many a heartbreak.

At no time in history, however, has the mood been altered so dramatically as in recent years when the "business" of sports infiltrated the game. Loyalty is waning as fans express discontent with what they perceive as team greed. Players' salaries have skyrocketed, and ticket prices alone cannot cover the colossal payrolls. More and more team owners are looking at the sports facility and its ability to make money through dollar signs in their eyes. And why not? Modern sports facilities are virtual gold mines.

Gone are the days of simple lease contracts between stadium owners and team owners as the stake in revenues has grown.

Professional sports are now big business generating billions of dollars each year and decisions are based on the "bottom line." Many team owners consider stadiums the key to profitable teams and threaten to leave if an old stadium is not upgraded or replaced. As a result, policymakers are often scrambling to retain their teams.

This report provides an overview of professional sports and the income capacity of modern facilities. It identifies key issues legislators need to address when considering public financing for sports facilities and provides financial details for all current sports venues in the form of a state-by-state chart.

Professional Sports in the United States

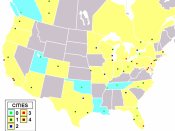

Currently, in the United States, 105 baseball, football, basketball and hockey teams exist at the major league level. Because some teams play in multi-purpose facilities, these 105 teams play in 83 different stadiums and arenas located in 24 states and Washington, DC.

Figure 1. States with Major League Professional Sports Teams

For the past six years, Financial World magazine has conducted a survey of professional sports team values. According to the 1996 survey, basketball teams are valued the highest as a multiple of revenues. Although football generates the most in total revenues, basketball teams are considered a better value. The typical NBA team is valued at 2.8 times its average revenues for the past three seasons. At the low end is baseball, where most teams are worth only a multiple of 2.2. Comparable figures for football and hockey franchises are 2.7 and 2.5 respectively. (1)

Teams are valued by their ability to generate net revenues, which usually reflects the income-generating capacity of the facility in which they play. Each league imposes its own rules about revenue distribution and team ownership. Because these regulations help determine the importance of stadium revenues to a team, the following sections provide a brief overview of the four major sports.

Baseball

Founded in 1876, Major League Baseball (MLB) is the oldest of the four commercial sports. MLB is divided into two different leagues (American and National), made up of 28 teams in the United States (including two recent expansion teams in Arizona and Florida) plus two teams in Canada. Regular season baseball begins in April and concludes in early October. In a typical season a team will play more than 80 games in its home stadium. Because of the large number of games, total attendance is higher for baseball than any other sport. As demonstrated by Figure 2, baseball attendance averages around 50 million fans per season while attendance for the other sports averages between 10 million and 20 million. Despite high attendance figures, total baseball revenues are not the highest of any league since baseball ticket prices are lower than other sports.

Figure 2. Attendance for Professional Sports Teams, by League 1993 - 1995 (in millions)

Source: Governor's Sports and Exposition Facilities Task Force Report, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, based on data from Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League. (Note that the 1994 and 1995 baseball and 1994-1995 hockey seasons were shortened by labor disputes.)

In addition to ticket receipts, MLB teams rely on the sale of broadcasting rights for financial support. Income from national television broadcasts is collected by the league as a whole and distributed to all teams. However, individual teams are permitted to sign local broadcast contracts and allowed to retain the cable and local broadcasting revenue. As a result, there is a wide disparity between the revenue of large media-market and small media-market teams. For example, the New York Yankees have a cable television contract worth more than $40 million every year. Compare that to several teams with local television contracts worth less than $10 million and the difference in purchasing power becomes apparent.

Prior to the 1997 season there was no salary cap in MLB. Combine that with free agency, and the immense salaries star players earn put them out of reach for all but a few high-revenue teams. According to many analysts, it is no coincidence that winning teams sport the highest payrolls. The New York Yankees and the Atlanta Braves were the two teams to battle it out for the 1996 World Series championship title; these two teams also happen to have the highest payrolls in MLB.

In late 1996, baseball club owners and players agreed on terms to settle a long running labor dispute. They agreed to interleague play, an assessment on payrolls commonly known as a luxury tax and an unprecedented level of revenue sharing between rich and poor clubs. The impact of this agreement remains to be seen, but obviously the luxury tax will affect those teams with large payrolls and revenue sharing will affect large market teams with major cable television contracts.

Football

The National Football League (NFL) was created in 1921 and now consists of 30 American teams in two conferences (American Football Conference and National Football Conference). Regular season play runs from September through December. NFL games are played weekly, so most teams are able to draw large crowds for their eight regular home games. Since there are fewer games, each one is important for the team and the home-viewing audience can be massive.

If baseball is the national summer pastime, watching football on television is a favorite cold-weather pastime. Every NFL game is carried by a national television network and Monday night football routinely receives high viewer ratings. As a result, the sale of broadcasting rights contributes tremendously to the revenues of NFL teams with football generating more broadcasting revenue than any other sport.

The NFL generates more in revenues than any other sport and NFL teams share more of their revenues than any other league. Nearly all of the total league revenue from merchandising and broadcasting is shared equally among team owners. Game day revenue from ticket sales is shared by the teams, with the home team receiving 60 percent and the visiting team 40 percent. Each team, however, is allowed to keep the revenues generated by the stadium (advertising, parking, concessions, seating, etc.). Because owners do not share stadium revenue, franchises with facilities that generate high stadium revenues tend to be valued higher than other teams.

Figure 3. Average Revenues for Professional Sports Teams by League, 1995 (in millions of dollars)

Source: Governor's Sports and Exposition Facilities Task Force Report, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, from Financial World, "Sports: The High-Stakes Game of Team Ownership," May 20, 1996.

The NFL has the most restrictive ownership regulations. Unlike other professional sports, publicly traded corporations may not own football franchises (the Green Bay Packers team was grandfathered in since it has been owned by a local nonprofit sharing corporation since 1923) and owners are not supposed to have outside interests in other teams (although this is currently being challenged in Florida). The other three leagues permit corporate ownership of franchises and more than one team may be owned by the same owner. This NFL rule effectively places even more importance on the stadium issue. Since NFL owners are more dependent on the profitability of their teams, they are more inclined to desire stadiums that generate higher revenues.

The NFL instituted a salary cap on players' salaries to contain costs in 1993. The minimum and maximum amounts a team can pay its players is determined by formula according to a percentage of designated league revenue where league revenue is made up of ticket sales and broadcasting revenue. Franchises have found a way to circumvent the salary cap, however, by offering hefty signing bonuses to desirable players. Only wealthy franchises with ample cash are able to offer substantial bonuses upon signing players, prompting many owners to claim that high revenue producing stadiums put their teams at a competitive advantage.

Basketball

Founded in the 1940s, the National Basketball Association (NBA) is made up of 27 teams in the United States and two in Canada. The NBA's regular season begins in October and runs through April with about 40 regular season games played at home. Many teams are owned by large corporations that also own hockey teams. Both teams often play in the same arena.

The NBA as a whole has contracts for national network broadcasts and revenues are shared by the teams, but each team may sell the rights to broadcast games on local television.

On the verge of a serious decline in popularity in the 1970s and 1980s, professional basketball made a dramatic comeback in the 1990s. The NBA has been very successful in promoting its star players--even to the point where fans of opposing teams will come just to see a star perform. Michael Jordan, for example, attracts sellout crowds wherever the Chicago Bulls play. In addition, basketball players, probably more than other athletes, receive high name recognition and are hired by corporations to endorse certain products.

A salary cap established minimum and maximum salaries for NBA players in 1983, but like the NFL, players are eligible for signing bonuses as incentives to join a particular team. The NBA has adopted an interesting policy in which players share team revenues with the owners. Under the latest collective bargaining agreement, the players get 59 percent of defined gross revenues and share in all sources of revenue including luxury suites, sponsorships, parking and concessions. This way, the players and team owners are both vested in the financial success of the franchise.

Hockey

The National Hockey League (NHL) was founded in 1917 and contains 21 teams in the United States and five in Canada. The season runs from October through April and about 40 regular games are played at home. Hockey has been popular for a long time in many northern states, but as more teams relocate in the South, the sport is gaining even more momentum. The NHL now has teams in the southern cities of Miami, Tampa, Dallas, Los Angeles and Phoenix.

The NHL contracts with national networks for broadcasting rights, but individual franchises can negotiate locally. The NHL signed its first long-term contract with a major broadcast network when it signed a five-year contract with the Fox network in 1995.

Also in 1995, a collective bargaining agreement was signed by the NHL and the NHL Players Association after a labor dispute cut the 1994 season short. At the core of the disagreement was the desire of team owners to impose a salary cap. In the end, owners were only able to get a $850,000 cap on rookie salaries and some other restrictions on free agency. Veteran players are committed to a salary arbitration process and may become unrestricted free agents at the age of 32.

Stadium Revenues

Media revenues and ticket receipts used to be the primary factors driving the value of sports franchises. Now stadium revenue is just as important. Income generated from sports facilities include rent plus revenues from parking, food and beverage concessions, team paraphernalia and merchandise, naming rights, stadium advertising, luxury seating and personal seat licenses. Stadiums have always generated revenues from many of these sources, but naming rights and personal seat licenses are newcomers to the stadium revenue stream. In addition, the ability to raise revenues through luxury seating has jumped dramatically.

Corporations pay millions of dollars for the privilege of naming stadiums and arenas. Bank One will pay the Arizona Diamondbacks $1 million a year over 30 years for naming rights to the stadium--that is more than some teams gross in stadium revenues all year. Miller Brewing just agreed to pay $40 million for the naming rights to the new stadium soon to be built in Milwaukee. Continental Airlines will pay $29 million over 12 years to change the name of an arena in New Jersey and the list goes on. However, the amount paid for naming rights can be misleading because a company that purchases naming rights may also be purchasing preferred vendor rights such as pouring rights, which is the ability to sell their product during events.

Personal seat licenses are also a relatively new revenue source. They give fans the right to buy a season ticket or specialty seating such as club seats.

Luxury seating includes special skyboxes usually purchased by corporations at premium prices and another level of more expensive seating often referred to as club seats. Club seat ticket holders often have better views, preferred parking, indoor/outdoor options and higher quality food and beverage service including a wait staff. Luxury seating alone is a tremendous moneymaker and is the second most important revenue stream for sports franchises behind television revenues.

Stadium revenues come in a variety of ways, and in today's brave new world of professional sports they are the key to profitable teams. This is why many team owners claim they cannot afford to keep teams in old stadiums without the tremendous earnings potential of special seating and other stadium income. The argument goes like this: a new stadium will generate more in revenues. In turn, the franchise will be in a better position to bid for quality players, which will result in a better team, which will draw more fans, which will result in more revenues and so on. Proponents claim that this argument is validated by the fact that most teams playing in new stadiums have seen attendance numbers increase and the teams have improved. Three of the four 1996 MLB playoff teams in the American League were teams that played in stadiums less than 5 years old. The only new stadium in the National League is Coors Field, host to the expansion Colorado Rockies--a team that made it to the playoffs in its third year of existence and first year of the new stadium.

On the other hand, many argue very convincingly that the new-stadium-leads-to-a-better-team theory doesn't hold true for two reasons: 1) Sound management with the ability to make wise draft choices, develop strong training programs and produce well-coached teams is what really matters; and 2) Most old stadiums have been renovated and modernized over the years to improve venue revenues.

Both points are illustrated by several championship teams playing in old stadiums. Fulton County Stadium and Candlestick (3Com) Park respectively have served the Atlanta Braves and the San Francisco 49ers very well. The Colorado Avalanche won the 1996 Stanley Cup while calling the 25-year-old McNichols Arena home, the Chicago Bulls won several championships in their old arena, and the New York Yankees won the 1996 World Series in "the house that Ruth built." But perhaps the best example is Texas Stadium, home of the Dallas Cowboys, which opened in 1971. The facility design and the design of the lease have proved to be very profitable for owner Jerry Jones and his team. The lease with the city of Irving allows the club to create and control new revenue sources at the stadium. After several stadium additions, the facility now boasts 370 luxury suites, which is 100 more than any other team. Not coincidentally, the stadium generates more in revenues than any other. How can a team that receives no stadium revenue compete for premium players against the extra $40 million Dallas brings in from the stadium? It's difficult, and as a result, Dallas has had a dominant NFL team for the past several years.

Therefore, it would seem that more generous lease arrangements and luxury boxes--not necessarily new stadiums--are what team owners desire. This is probably true, but in some cases there may be no chance to re-negotiate the lease with the facility owner or it may not be economically feasible to renovate the stadium. Or in some stadiums, there may be no revenues to negotiate if the maintenance costs of the facility are high. The city of Oakland, however, determined that it made sense to renovate the Oakland Coliseum and recently spent $127 million on improvements as part of the deal to bring the Raiders back to Oakland.

Economics of Sports Facilities

Are new stadiums a good public investment? The issue is hotly debated by advocates on both sides. The answer rests with several factors: stadium lease agreements, the amount of new money entering the economy, the number and quality of new jobs, charitable contributions and other intangible items.

Stadium lease agreements--Traditionally, in publicly financed, publicly owned facilities, the city keeps most of the revenues generated from the facility to offset the costs. But that has changed in recent years as teams have successfully negotiated with government officials for a greater share of stadium revenues. Several teams have negotiated very favorable deals where taxpayers foot the bill for a new stadium, but the team retains the revenues. Take the Colorado Rockies, for example. Coors Field opened in 1995 with a price tag of $215 million. The Rockies contributed $53 million or 25 percent and the rest was paid by Denver-area taxpayers through a 0.1 percent sales tax. The Rockies have a 22-year lease and pay no rent unless the annual attendance figure hits 2.25 million; then they pay on a sliding scale based on attendance. In exchange they pay all operating and maintenance costs of the stadium and keep all revenues from concessions, luxury boxes, the naming rights and stadium advertising. They also receive 80 percent of parking revenues during game days and 20 percent of parking revenue from other events at the stadium. This agreement is not unusual, several teams have similar deals including teams in Missouri and Maryland.

New money entering the economy--Economic impact includes both direct spending by visitors and the indirect spending, or re-spending, of those same dollars by businesses that receive them. Many economists have found that using public dollars to finance sports stadiums does not provide a good return on the investment since sporting events are generally attended by local residents with limited disposable income. Money spent on sports is money that may have been spent elsewhere. In other words, new money is not entering the local economy unless the team draws spectators from outside the area and they stay and spend money in the community. From a state perspective, drawing visitors from out of state provides the greatest boost to the economy, but most sports teams do not draw many out-of-state visitors.

The most widely known academic studies on the economic impact of professional sports have been conducted for the Heartland Institute by Robert Baade of Lake Forest College and Dean Baim of Pepperdine University. Both studies reached the same general conclusion that rarely are there net economic benefits to cities that subsidize sports facilities. (2)

Some urban facilities, however, built in blighted areas, have had positive spin-off effects that no other type of development could have matched due to the regional support for professional sports. Not only did the facilities stimulate development in the immediate area, but it happened with help from entire metropolitan areas. It is unlikely that suburban counties would ever subsidize core-city development in any other circumstance.

Creation of new jobs--The argument in favor of sports as an economic development tool is boosted by the fact that sports franchises create new jobs. Construction jobs are created when new stadiums are built and in the surrounding area if it develops as well. The franchise also hires people directly. There is no question that players are paid handsomely. Plus franchises have office staff and hire seasonal employees to work the games. In turn, those people spend money in the local economy and everyone pays state and local taxes. Question are raised, however, about the quality of some of the jobs and about whether the same amount of investment in another business would contribute as much if not more.

Charitable contributions--One of the more tangible benefits of professional sports is the impact on charitable contributions. Several sports teams make sizable contributions to charities in their communities and have created special foundations. In addition, although many question sports figures as role models, many professional athletes have made great personal contributions to their communities and serve as positive role models.

Intangible factors--Finally, some benefits, like community pride, the pleasure derived from sports, and the joy in having a home-town team, are difficult to measure. Therefore, regardless of whether it makes economic sense to build a new stadium, it often makes political sense when the high profile nature of professional sports and other intangible factors are taken into account. Policymakers are then faced with the difficult task of deciding how to fund the stadium.

Key Considerations for Policymakers

Identify need for a new stadium--What are the real reasons behind the team's desire for a new stadium? Does a suitable stadium already exist? Has the value of the team declined because the team receives little or no stadium revenue? Does the existing stadium produce revenues? If so, would it be possible to re-negotiate the lease agreement so that the team receives a greater portion of the revenues? Does the stadium lack only lucrative luxury seating and corporate boxes? If so, how difficult would it be to add those things?

Identify an appropriate site--Once the decision has been made to build a new facility, think about the ideal location. Due to their downtown locations, new stadiums in Baltimore, Cleveland and Denver are considered catalysts for major urban development projects. Because economic benefits from sports facilities are a result of pedestrian and vehicular traffic, stadiums work best when situated centrally in a pedestrian-friendly environment near restaurants, bars, hotels, parks, museums, shops and other interesting places. Visitors are then encouraged to do other things and spend more money in addition to attending a game. Generally, suburban facilities are only accessible by car and seldom is anything else nearby. Fans drive to the stadium, park in large parking decks, attend the game, return to their cars and go home. Some franchises, however, deliberately isolate their stadiums to better monopolize parking and concession revenues. It should be noted that this model does not contribute much to economic development.

Determine the Facility Cost--What features will the new facility contain and what will they cost? Because fans like to sit outdoors on nice days and indoors in inclement weather, the current trend is for retractable roofs, which drive the cost up considerably (they range from $300 million to $500 million). A retractable roof stadium was recently constructed in Toronto and one is currently under construction in Phoenix. In addition, new retractable roof baseball stadiums have been proposed in both Seattle and Milwaukee. In general, any kind of dome costs more than an open facility, although maintenance costs for grass is greater than for artificial turf.

Another thing to consider is the cost of borrowing money. If bonds are used to finance stadium construction, interest on the bonds must be included as part of the debt service schedule, but is seldom included in the cost estimates.

In addition, there are usually real and opportunity costs associated with re-negotiating an existing lease. If terms of a new contract are changed in favor of the franchise, the city or facility owner will receive less in revenues. Less public revenues are likely to have ramifications throughout the community if those revenues help subsidize other city programs or facilities.

Who Will Pay for the Facility

There are several options:

The general public pays. The general public is forced to pay when a new tax is imposed or if general fund revenues are used to fund the stadium. For example, voters in Hamilton County, Ohio, recently approved a general sales tax increase of 0.5 percent to raise the money for one (or possibly two) new stadiums in Cincinnati.

The fans or users of the facility pay. Fans bear most of the burden for new stadiums when stadium revenues are used to finance the facility. The new Ericsson Stadium in Charlotte, N.C., was largely funded through the sale of personal seat licenses.

The franchise pays. The franchise pays when the team contributes directly to the cost of the new stadium or arena. Facilities in California, Massachusetts, Florida and several other states were built with private funds and are privately owned. However, even with privately financed facilities, the city or state often provides roads and infrastructure as well as special tax breaks that are not available to other businesses.

Targeted beneficiaries pay. Targeted beneficiaries are those businesses that benefit directly from the facility. For example, restaurants and bars located near the stadium receive additional business on game days. By imposing a sales tax on such businesses in a defined geographic area and earmarking it for the facility, it is possible to shift some of the burden onto the businesses that directly gain from sports-related activities. However, it is difficult to measure who really benefits and by how much so this type of proposal is likely to be met with much opposition.

Some combination of public and private money is used to pay for sports facilities. The most acceptable financing strategies are designed to use a mix of various funding sources.

Finally as part of any financing arrangement that includes public funds, it is important to ensure that the community is protected from excessive costs. One way to accomplish this is to place a cap on the amount of public funds to be used. Any cost overruns must be absorbed by the team. Be aware, however, that league restrictions may exist. For example, the NFL prohibits teams from assuming more than $55 million in debt.

Financing Options for Sports Facilities

Historically, stadiums were often built as public works projects, but over time, public sentiment has shifted as costs have escalated. The ability of stadiums to make money also has attracted more interest from the private sector. Team owners are now willing to contribute to the cost of new stadiums so they can negotiate for stadium revenues. Almost all the new stadium deals involve private funds (see table 1). In fact, many of the arenas used for hockey and basketball have been funded almost entirely with private funds. These arenas are more profitable because they can be used throughout the year for concerts and other events, and they are smaller and less expensive than the large single or double purpose facilities used for baseball and football.

Of the 83 professional sports facilities in use in the United States, 24 have been built since 1990. In addition, several new stadiums are in the planning or construction phase including one in Nashville, Tenn., where officials successfully negotiated with the Houston Oilers to move there for the 1998 season. Most new stadiums have cost between $200 million to $300 million to construct.

Table 1. New Stadiums Since 1990

StadiumTeamCapacityYear OpenedOriginal Cost* (millions)% Publicly Financed

Bank One BallparkArizona Diamondbacks48,5001998 (1)$338.0 (2)75%

Cumberland StadiumUndetermined76,0001998 (1)$292.0 (2)100%

CoreStates SpectrumPhiladelphia 76ers21,0001996$206.00

Philadelphia Flyers19,500

Marine MidlandBuffalo Sabres21,0001996$122.045%

Ericsson StadiumCarolina Panthers72,3501996$247.720%

Ice PalaceTampa Bay Lightning19,5001996$139.062%

Jacksonville StadiumJacksonville Jaguars73,0001995$135.090%

Key ArenaSeattle SuperSonics17,1021995$114.082%

FleetCenterBoston Celtics18,6241995$160.00

Boston Bruins17,565

Coors FieldColorado Rockies50,1001995$215.075%

Rose GardenPortland Trail Blazers21,4011995$ 94.014%

Trans World DomeSt. Louis Rams65,3001995$299.096%

Kiel CenterSt. Louis Blues18,5001994$138.846%

Gund ArenaCleveland Cavaliers20,5621994$159.397%

Ballpark at ArlingtonTexas Rangers49,2921994$196.071%

Jacobs FieldCleveland Indians42,4001994$177.888%

United CenterChicago Bulls21,7111994$180.09%

Chicago Blackhawks20,500

San Jose ArenaSan Jose Sharks17,1901993$179.082%

AlamodomeSan Antonio Spurs20,6621993$196.0100%

Arrowhead PondMighty Ducks of Anaheim17,2501993$ 84.3100%

America West ArenaPhoenix SunsPhoenix Coyotes15,5001992$ 97.739%

Georgia DomeAtlanta Falcons71,5941992$232.4100%

Oriole Park-Camden YardsBaltimore Orioles48,0001992$228.096%

Delta CenterUtah Jazz19,9111991$100.60

Comiskey ParkChicago White Sox44,3211991$167.8100%

Target CenterMinnesota Timberwolves19,0001990$117.073%

ThunderDomeTampa Bay Devil Rays46,0001990$171.0100%

1.Scheduled [back] 2.Projected [back]

* Cost figures for facilities built prior to 1995 have been adjusted to 1995 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. [back]

Once the decision has been made to use public funds for a new stadium, there are a number of options. Options previously tried by state and local governments include: general fund revenues, general sales taxes, tourism taxes, excise taxes, stadium revenues, personal seat licenses, state lotteries, ticket surcharges and government backed bonds.

Generally, bonds are issued by a state, city, county or special authority. States' ability to use bond instruments, however, is often restricted by legal limitations regarding the amount of debt they can assume. If the use of bonds is restricted by statute, legislative action is needed to initiate a bond issue. If bonds are prohibited by the state constitution, voter approval may be required to authorize the issue. Municipalities also have the ability to issue bonds.

Bonds can be either general obligation bonds backed by the full faith and credit of the issuing party or they can be revenue bonds backed by some specific revenue stream. General obligation bonds usually require voter approval and revenue bonds sometimes do. Prior to 1986, tax-exempt revenue bonds were often used to finance sports facilities because they carried a lower interest rate and were therefore less expensive. Federal tax changes, however, in 1984 and 1986 placed restrictions on governments' ability to finance stadiums by prohibiting the use of tax-exempt bonds for a private activity. Now to use tax-exempt bonds, the issuing authority must ensure that no more than 10 percent of private stadium revenues are used to pay the debt service. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York has twice introduced federal legislation that would place further restrictions on financing sports facilities with tax-exempt bonds. The 1997 legislation is currently pending.

A number of states have created special stadium authorities or districts to build and manage sports facilities as separate quasi government entities with bonding authority. Special authorities can be entities of the state as in Illinois, New Jersey and Maryland or they may be local metropolitan districts as in Phoenix, Denver, Tampa, Miami, Atlanta, Indianapolis, St. Louis and Pittsburgh.

Revenue bonds are frequently used to finance sports facilities where stadium revenues are used to repay the debt. Stadium debt in North Carolina and Florida is paid, in part, with revenues generated from the preliminary sale of luxury seating and personal seat licenses. Personal seat licenses, however, work best in new markets where fans are willing to pay a premium just for the privilege of buying a seat. In markets where teams exist, it is difficult for the franchise to go to current season ticket holders and ask them to pay for a personal seat license.

Stadium revenues may also be supplemented with other operating revenue. For example, stadium debt for the New Jersey Meadowlands sports complex is serviced with revenues generated from a horse racetrack located in the complex.

Other states have authorized use of special local option taxes to service the debt for sports facilities. Local governments in Illinois, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri and Washington use lodging taxes as one way to raise money for new stadiums. Lodging and other tourism taxes tend to be some of the easiest taxes to gain voter approval. Local voters like them because they are able to shift the costs to tourists who stay in hotels or rent cars. In Florida, St. Petersburg and Jacksonville added a one-cent lodging tax to help fund their stadium debt. The Atlanta Falcons' stadium is paid for, in part, with 39 percent of a seven-cent lodging tax in Fulton County. An additional 2 percent tax is levied on Chicago hotels to help pay for the White Sox park, a 4 percent lodging tax is imposed in two Louisiana parishes to help pay for the Superdome, a county-wide lodging tax helps fund debt for the TWA Dome in St. Louis, a 2 percent county-wide lodging tax helps pay for the KingDome in Seattle and voters in Detroit just approved an additional lodging tax to help fund a new downtown football stadium.

Cities, counties and special districts in Arizona, Colorado, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin adopted increases in their general sales tax rates to raise money for stadiums. The legislature in Ohio approved a ballot measure asking voters to approve new excise taxes on tobacco and alcohol in Cleveland--which they did. Local governments in Colorado and Florida impose surcharges on tickets to events in city-owned facilities. In Indiana, Marion county imposes an additional tax on motels, meals, cigarettes and admissions to pay the stadium bonds and in Washington an additional 2 percent car rental tax is imposed in Seattle to help fund a new stadium for the Mariners.

Sometimes state money is used to fund sports facilities. The Georgia Dome in Atlanta was financed mainly with state funds. In Maryland and Washington, state lottery funds are used. The state legislature in Maryland authorized two new sport-themed lottery games. The money generated from those games will be used to repay the state stadium debt. These lottery games were extended to help fund a new football stadium as part of the deal to bring the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore. The state of Washington also agreed to help fund a new baseball stadium in Seattle and created two new lottery games to generate the revenues.

In 1988, Florida created a special state tax rebate program to lure new teams to the state. Eligible teams may receive up to $2 million per year for 30 years. Michigan recently authorized the use of $55 million from the Michigan Strategic Fund for a new stadium. To help finance a new stadium in Tennessee, lawmakers passed legislation permitting municipalities to create sports authorities that would be allowed to retain the 5.5 percent state sales tax on all revenues from the stadium. In addition, the state agreed to finance $12 million in infrastructure and to issue bonds to build the stadium if the income collected by the local sports authorities from the state sales tax would be returned to the general fund.

Conclusion

The evolution of sports from a game to big business is clear. Teams generate revenues from television and radio broadcasts, and corporations pay franchises and individual athletes huge sums to promote their merchandise. Player and team loyalty seem like outdated concepts as financial considerations influence most decisions. It is extremely rare for a player to spend his entire career with one team. Likewise, teams are often owned by major corporations that are swayed by bottom-line profits.

Talented players have an unprecedented ability to command high salaries, which are the major expenses for all sports leagues. Ticket prices have increased substantially over the years, but not fast enough to cover the enormous salary expenses most franchises face.

The ability of stadiums to generate revenues has increased dramatically and now plays a much greater role in teams' ability to compete and afford players' high salaries. As a result, owners are holding cities hostage with demands for new stadiums and public subsidies. The current demand for sports franchises is such that a community somewhere is likely to meet those requests. Policymakers are then faced with the tough choice of meeting team demands or losing the team.

If the decision is made to use public money to fund a new stadium, policymakers are wise to design a fair and equitable financing package after evaluating all available sources of financing and using an optimal mix of these potential sources. And as part of any financing arrangement, policymakers must ensure that the community is protected from excessive costs.

Circumstances differ among the states and among the various cities and counties. But one thing is clear. Regardless of the costs, sports are woven into the American fabric. No other industry has been able to create the same sense of civic pride and garner the same emotional support as professional sports. As long as stadiums continue to generate revenues and as long as teams seek better stadium deals, the debate on the public financing of stadiums will continue.

Appendix A

Financing Professional Sports Facilities

Notes

1.Tushar Atre, Kristine Auns, Kurt Badenhausen, Kevin McAuliffe, Christopher Niklov and Michael K. Ozanian, "Sports: The High Stakes Game of Team Ownership," Financial World, May 20, 1996, 55. [back]

2.Robert A. Baade, Stadiums, Professional Sports, and Economic Development: Assessing the Reality (Detroit, Mich.: The Heartland Institute, 1994).

Dean V. Baim, Sports Stadiums as "Wise Investments": an Evaluation (Detroit, Mich.: The Heartland Institute, 1990). [back]