In France, the revolutions started with a riot by the Parisians, which, after Louis Philippe's fleeing to Britain, led

to the formation of the second republic. Yet, after the new government had settled in, the people grew more discontent

with their situation. There was in fact disunity in the second government, as Louis Blanc, obviously known for his

socialist views, was at odds with the rest of the ten man liberal government. The bloody June Days gave the Parisians

a chance to battle the government troops. The result was a new monarch-to-be, and a move back to where the revolution

had started. Throughout all of this, it is important to note that it was only the Parisians (the first people to riot)

that were active in the revolution. They (the upper middle class men) were the ones that participated in the

government, and that fought to the death in this revolution.

The farmers and peasants, on the other hand, seemed to be

to preoccupied with their agricultural problems (such as the continuing poor outcomes of the crop harvests) in the

countryside. And while there was disunity among the leaders of the revolution, the revolutions actually failed because

the peasants (which made up a huge majority of the population-not only in France but the rest of Europe as well) were

not involved, the revolution really did not have the power needed to fight against an army with the strength of the

French one.

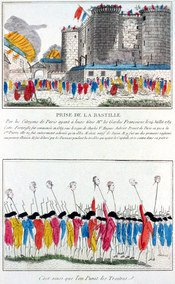

The events of the French Revolution alternately energized and repulsed contemporaries. Many experienced what English

poet William Wordsworth immortalized in his poem French Revolution As It Appears to Enthusiasts (1804): "Bliss was it

in that dawn to be alive/ But to be young was very heaven!" The French overthrow of the old regime and all it stood

for was celebrated and commemorated in songs, engravings, poems, paintings, and music. Some, like Wordsworth, even

voyaged to France to see events firsthand. Yet from the first months of the Revolution, others saw a darker side of

the unfolding drama. The first major debate about the French Revolution outside of France was sparked by a lively

polemical tract written by Edmund Burke just months after the fall of the Bastille. A member of the British

Parliament, Burke had gained a reputation defending the Americans in their revolt against the British crown. He was

much less favorably impressed by the French Revolution, however. In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), he

expressed reservations about the revolutionaries' reliance on reason as the sole standard of government and predicted,

quite presciently it turned out, that the French would eventually turn to violence to enforce their decisions. Burke

went beyond criticizing the French revolutionaries; he offered the first systematic defense of "conservative"

principles, arguing that gradual change and a kind of organic continuity in society stretching across the generations

were preferable to violent, rapid upheavals in the structure of government. From its very beginning then, the French

Revolution stimulated profound political controversy and equally profound rethinking of the nature of government

itself. Because the revolutionaries aimed to rebuild government from the foundation upward, substituting reason for

tradition and equal rights for privilege, they inevitably provoked wide-ranging reactions.

Socialists and communists had a more positive view of the French Revolution: they considered it an important harbinger

of the future. However, they wanted to go beyond its tentative promises of individual rights and legal change within a

constitutional order. Socialists and communists believed that the French Revolution had not gone far enough. The

founders of communism as an international movement, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, both commented extensively on the

French Revolution, hoping to find in those events important lessons for the future course not only of communism but of

history itself.

The French Revolution clearly had repercussions throughout the world. For example, the Napoleonic occupation of Spain

in 1808 was the spark that ignited the independence movement in Latin America. Beginning with Mexico in 1810, Central

and South American local elites declared their independence from Spain and Portugal. Most countries achieved

independence in the 1820s. Others, like the revolutionary Simon BolÃÂvar, rejected the control of these elites,

preferring to follow the example of Haiti. The spread of nationalism to Latin America was accompanied by some of the

other liberal ideas associated with the French Revolution, but not by all.