In April 2004, Wal-Mart announced a pilot program that would require its top 100 suppliers to be RFID compliant -- attaching Radio Frequency Identification tags on cases and pallets destined for Wal-Mart stores and Sam's Club locations in the Dallas/Fort Worth area -- by January 2005. Showing just how much clout Wal-Mart has, the retailer is boasting 100% compliance, although it won't know until next month whether the system has led to increased efficiencies.

"If it wasn't for Wal-Mart, we would not be having this conversation," says Badri Devalla, principal architect with Infosys, a global consulting and information technology services company, who spoke about the future of RFID technology at a recent Emerging Technologies conference. While the technology has definitely come into its own, said Devalla -- pointing out that the automotive industry and the Department of Defense have been exploring RFID for the past few years -- it took a giant like Wal-Mart to bring it to the consumer goods sector.

"Initially suppliers were scrambling to comply. Now many are stepping back and asking the million-dollar question: 'Is this just a sunk cost, or can we find a way to benefit from it?'"

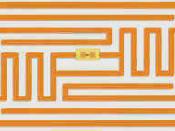

Interestingly, while it may be considered one of the hottest technologies around, RFID is fairly old. It was invented in 1948 by Harry Stockman, but until the late 1990s it was essentially a technology waiting for an infrastructure. Its three components include the tag (a digital memory chip with integrated transponder), a reader (senses the presence of tags, receives and processes tag-level data) and a host computer (aggregates data from tag readers and passes RFID data via middleware to core business systems). Before powerful enterprise-wide computing, there was nothing to do with the information, so there was no reason to collect it. After Y2K and the...