� PAGE �2�

Laurentian University

Reformation Causes Essay

HIST 2116

Zakk Bartsch

October 7, 2008

Zakk Bartsch

Dr. Liedl

HIST 2116

October 7th, 2008

Reformation Causes: Nationalism

Reformation in medieval Europe can be said to have many causes and factors for its uprising, which at the same time could also be argued not to have been. Nationalism, however, played a major role in reformation, especially in Germany. Nationalism in Germany has been identified by some as emerging as early as the late fifteenth-century reform movement, or seen as the underlying cause of the sixteenth-century turmoil unleashed by Martin Luther's revolt.�

Martin Luther was a German reformer, humanist, university professor and theologian, amoung other things. He would go on to play a key role in the nationalism and reformation sentiment which were coincidently well suited for each other.

German humanism had always contained a strong element of nationalism. It vaunted the triumphs of German arms and letters in opposition not merely to ancient Rome but also to the supercilious claims of modern Italians to be owners of a higher culture.�

Throw in papal exactions that were heavily imposed on the Germans and anti-Italian sentiment readily became anti-papal sentiment. In order for nationalism to even exist there must be other rival nations, and with such remarks and cynicism, coupled up with the Church's inability or unwillingness to reprimand immoral priests and the restraint of clerical money-raising, who better than Rome.

Jakob Wimpfeling went on to spur such feelings with Germania, challenging Pius II's worldview and claims that Germans owed civilization and salvation to the Romans, and that Italians were the natural leaders of Christianity. Wimpfeling rather believed and felt that German Emporers and their piety did more for the Church than Roman corruption achieved. One could argue Wimpfeling felt this way because he bitterly resented the flow of money and resources from Germany to "the bottomless pit of Rome," which instilled nationalism.

Moreover, the Holy Roman Empire which consumed Germany was neither holy, Roman, nor an Empire. This realization by Ulrich von Hutten and the sentiment felt by Germans who were still being exploited for heavy tithes of assorted annates and tributes to the papacy, which both France and England had long ceased to pay�, was a calling for reformation. The corruption was becoming clear and evident to German humanists and educated elite.

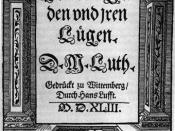

Luther would become acquainted with von Hutten and would similarly write a strongly worded appeal, in German, to the princes of the Empire; An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation (To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation), where he called upon the German Nobility to rise up against the unjust dominion of the pope.�Luther charged that the papacy had thrown up three walls around itself which must be broken down. These walls were the claims that (1) the church is superior to the state, (2) the pope alone has right to summon councils, and (3) the pope alone has the right to interpret Scriptures.

Luther wanted the papacy must be confined to a spiritual realm, and the church in Germany must be German. Needless to say, this stimulated the already building nationalism the people were beginning to feel, and thus fueled the reformation machine. Denouncing the foundation of the papacy's authority in Germany, calling upon the ruling class to lead a reform of the church, only enforced the ideas of a non-corrupt papacy and church and a Germany no longer exploited and revered.

Additionally, Luther wanted see the end to the swindle of indulgences, where a Christian may makes a payment to the Church as then exempt from going to Purgatory for any sins they may have caused, or even for ones they had yet to even commit. Luther wrote up his ninety-five theses in response to this scam, which were then translated into German and distributed throughout the empire. This gained Luther notoriety and his cause was born.

By the time of Charles V's rule, Luther's reform movement was coming to full swing. Luther's national movement, which supported the Hapsburg Emperor, gave the German people knowledge of their own ancient and glorious nation. They learnt of their own early liberation from the Romans and of many later conflicts between Emperor and Pope. With the introduction of the printing press, Germans now had more than ever before, access to pictures and writings of such feats building the growing patriotism.�

By 1526 the German princes were beginning to grasp that the pope was a single-minded political power, which might so clash with the Emperor that chaos would ensue in Germany. This resulted in not only having to defend themselves against rebellion, riot and insubordination, but to purify the Bible, in both flesh and spirit, from the multiple abuses of Rome. � The German rulers ultimately began to make alliances with each other. This opened their eyes to the power they have if they unite together, furthering the revolts against the Church and enforcing the reform. To end the days of corruption was the goal of this newly formed Schmalkaldic League, later defeated by the Catholic Emperor who was angered at their confiscation of Church property. Nevertheless this was a strong example of nationalism being a significant cause for the reformation.

Figures such as von Hutten, Luther, Wimpfeling, etc⦠did well to unveil the dishonesty and corruption of the Church and more so of the papacy and their exploitation of the German people.

To conclude, nationalism and the reasons that brought the people together were key aspects in driving a false empire to revolt against the papacy's regime and the corruption it brought upon the Church.

Bibliography:

Snyder, Louis L. Roots of German Nationalism. Bloomington/London: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Brandi, Karl. The Emperor Charles V. London: A.w. Bain & Co. LTD, 1939.

Hoffmeister, Gerhart. The Renaissance and Reformation in Germany. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1977.

Jensen, De Lamar. Reformation Europe. Lexington, Massachusetts Toronto: D.C. Heath & Company, 1992.

Dickens, Arthur Geoffrey. The Age of Humanism and Reformation. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1972.

� Louis L. Snyder, Roots of German Nationalism (Bloomington/London: Indiana University Press, 1978), vii.

� Arthur Geoffrey Dickens, The Age of Humanism and Reformation (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1972), 133.

� Gerhart Hoffmeister, The Renaissance and Reformation in Germany (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1977), 115.

� De Lamar Jensen, Reformation Europe (Lexington, Massachusetts Toronto: D.C. Heath & Company, 1992), 63.

� Karl Brandi, The Emperor Charles V (London: A.w. Bain & Co. LTD, 1939), 124.

� Karl Brandi, The Emperor Charles V (London: A.w. Bain & Co. LTD, 1939), 246.