The Great War, a conflict spanning four years from 1914 to 1918, drew countries from across the globe into the First World War. The power struggles in Europe between old and emerging empires erupted into open warfare with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Hapsburg Empire. A Bosnian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, shot and killed the Archduke and his wife in Serbia , creating the flashpoint for the outbreak of war. The central powers of Europe, namely Germany and Austria-Hungary fought against the European powers of France, Britain and Russia. When King George V formally declared war against the German nation on 3 August 1914, Australia, India, and New Zealand and others, were also at war as part of the British Empire. This essay will examine the role that Australian soldiers played in the Great War through the use of two case studies; the Gallipoli campaign and AustraliaÃÂs involvement at Pozieres.

Even though other Dominion countries including New Zealand, Canada and India all provided men and materials for Britain, this essay will focus primarily on the Australian forces.

On the 25th of April, 1915, British Imperial forces, including the Australian contingent, landed on the shores of Gallipoli. The invasion was part of the grand strategy of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. The stated strategic aims of the Gallipoli campaign were threefold: ÃÂto secure Egypt, to induce Italy and the Balkan States to come in on [the British] side, and, if followed by the forcing of the Bosporus, would enable Russia to draw munitions from America and Western Europe, and to export her accumulated supplies of wheat.ÃÂ Other advantages could be drawn from the potential success of the campaign, including the potential to attack the Central Powers from the south. If the campaign could successfully ÃÂknock Turkey out of the warÃÂ then, with the assistance of the Balkan states, the allies could potentially create a new front against the Central Powers. A new front could relieve pressure on the deadlocked and static Western Front.

The Australian force landed at Anzac Cove in the early hours of the morning. The terrain that awaited the assaulting Australians was difficult and varied, consisting of ÃÂscrubby knolls and ridgesÃÂ , ÃÂravines and rocky gulliesÃÂ and ÃÂrugged cliffs loom[ing] over a narrow strip of sand.ÃÂ The very nature of the terrain, coupled with the inexperience of the Australian forces, made coherency between advancing units difficult, if not impossible. Given the orders to ÃÂpush on at all costsÃÂ through such difficult terrain, it is no surprise that the impetuous pursuit of retreating Turks led Australian soldiers into untenable positions or enemy reinforcements. Even though Australian forces enjoyed some measure of success in their landing, managing to storm the cliff tops with .303 Lee-Enfield rifles and bayonets, the ÃÂcampaign at Anzac had gone from an invasion to a siege in one day.ÃÂ As the Gallipoli campaign developed into a static, trench dominated stalemate nearly identical to the style of warfare on the Western Front, the weaknesses of the invading Imperial forces became apparent.

The use of artillery in massive numbers was demonstrated daily on the Western Front, but at Gallipoli the Australian forces were supported by ÃÂonly 118 artillery pieces instead of their ÃÂestablishmentÃÂ of 306.ÃÂ This lack of artillery pieces, coupled with the shortage of ammunition, meant that any shelling in support of Australian assaults or defences was weak at best. Tactically Australian forces were wasted in the Gallipoli campaign. British orders constituted direct assault on entrenched and fortified Turkish positions, which received support from machine gun and artillery fire. At times Australian troops were used as little more than cannon fodder. At the Nek, the terrain was such that there was only enough room for 150 men abreast , attacking a Turkish position held by ÃÂhundreds of rifles and five machine guns.ÃÂ The 8th Light Horse suffered 234 casualties, 154 fatalities, out of the 300 soldiers in the regiment. The 10th Light Horse suffered 80 killed and 58 wounded.

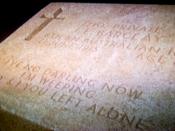

The casualties suffered by the Australian forces during the Gallipoli campaign totalled 26,111 of which ÃÂ362 officers and 7,779 other ranks were killed in action, died of wounds or succumbed to disease.ÃÂ The most successful part of the operation was the retreat, in which not a single man was lost to enemy fire. In the eight month campaign nine Victoria Crosses, the highest military award in the Australian Army, were awarded to Australians. Seven of those nine VCs were won during the Battle for Lone Pine. Over eight thousand Australians were lost during the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. As difficult as Gallipoli was for Australian soldiers, their deployment to the Western Front would show them the true horror and futility of the First World War.

The trenches of the Western Front introduced the Australians to a new facet of warfare. Having experienced rifle, machine gun and artillery fire at Gallipoli, the Australians could be thought of having seen war. However, on the Western Front the soldiers on both sides of the line suffered attacks from gas weapons, unceasing artillery, flamethrowers and, in the latter stages of the war, assault from tanks. The prosecution of warfare on the Western Front followed the ÃÂdirectÃÂ approach of the continental school of warfare, a school of strategy ÃÂconcerned with ground warfare between armies.ÃÂ The basic premise of the direct strategy was to bring ÃÂsuperior force to bear on a point where the enemy is both weaker and vulnerable to crippling damage.ÃÂ Clearly demonstrated, by both the Central Powers and the Allied forces, was the willingness to throw millions of munitions and men at the enemy, with little or no regard for the cost.

The Australian attack at Pozieres was another example of the direct strategy. ÃÂThe artillery barrage began at precisely at 12:28 a.m. For two minutes every gun in the division fired as fast as their crews could load,ÃÂ after which the Australian troops, lying in wait in No ManÃÂs Land, rose to assault the bombarded German trenches. It took two hours for the Australians to capture the trench at Pozieres, and almost seven weeks to deny the German counter-attacks that started immediately upon the Australians capturing the trenches. The Germans ÃÂmade not less than 67 counter-attacks. ÃÂProbably they had made a great many more . . . possibly twice as many.ÃÂ These counter-attacks were characteristic of German policy which was ÃÂto counter-attack vigorously, both local counter-attacks [and] massive planned assaults.ÃÂ Initial counter-attacks consisted of ÃÂabout 200 GermansÃÂ ; subsequent assaults were made in force with proceeding artillery bombardment of the Australian trenches. Five Victoria Crosses were awarded to Australians who had participated in the battle around Pozieres.

Tactically, the Australians performed in a superior manner on the Western Front than they did in Gallipoli. Part of the reason for this is the Australian contingent was placed under the command of a variety of Australian officers. Generally speaking, the Australian commanders, specifically General John Monash, were willing to preserve the lives of the men under their command. One tactical feature of the Australian trench war was their excellent use of small unit tactics. Known as minor aggression or peaceful penetration, small units would cross No ManÃÂs Land, kill or capture the enemy and then withdraw. This tactic ÃÂMonash described . . . as ÃÂa brilliant success.ÃÂÃÂ300,000 Australians were deployed in various theatres during the Great War and 60,000 were killed. Faced with a mishandled gamble in the Gallipoli campaign, Australian forces acquitted themselves with honour and continued that trend on the Western Front. With sixty five Victoria Crosses awarded to Australian soldiers during the Great War , the untried and untested Australians forces proved that they could fight with courage, honour and sacrifice. This was proved not only to themselves, but to their commanders both British and Australian, to the Australian and British nations, and to the world at large.

BibliographyBlair, D., ÃÂ25-29 April 1915: A landing and a legend establishedÃÂ in Dinkum Diggers: An Australian Battalion at War, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2001, pp. 7 - 86.

Carlyon, L., Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2001.

Charlton, P., ÃÂPozieresÃÂ in AIH338 Australia and the World Wars, Reader, Deakin University, Geelong, 2007, pp. 1 ÃÂ 7.

Cochrane, P., Australians at War, ABC Books, Sydney, 2001.

Grey, J., A Military History of Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1990 .

http://www.anzacday.org.au/education/medals/vc/austlist.html Accessed 8/8/07.

Malik, J. M., ÃÂThe Evolution of Strategic ThoughtÃÂ in Craig Snyder (ed.), Contemporary Security and Strategy, Macmillan Press, London, 1999, pp. 13 ÃÂ 52.

Shermer, D., World War I, Octopus Books Limited, London, 1973.

Terraine, J., ÃÂThe Gallipoli CampaignÃÂ in AIH338 Australia and the World Wars, Reader, Deakin University, Geelong, 2007, pp 1 ÃÂ 11.