Johnson - Jeffries Fight Jack Johnson began his life in Galveston, Texas, on March 31, 1878. He was the second of six children to Henry, a former slave, and Tiny Johnson. His family was very poor causing him to leave school in the fifth grade to work odd jobs around South Texas. He started boxing by fighting in "battles royal," matches in which young black children entertained white spectators who threw money at the winners (www.famoustexans.com, pg.1). He soon earned himself the name "Little Artha (Encyclopedia Americana, pg.129)." Johnson began touring with black fighters winning nearly all his matches. He turned professional in 1897 following a period where he fought in private clubs in hometown, Galveston. He was arrested in 1901 and jailed because boxing was a criminal profession in Texas. After his release, he soon left Galveston for good.

In 1908, Johnson was matched with white champ, Tommy Burns in Sydney, Australia.

Johnson won in the fourteenth round. The white public resented Johnson's flamboyant personality and wanted a "white hope" to dethrone him. Jim Jeffries would be their attempt.

Jim Jeffries was born in Carroll, Ohio on April 15, 1875, but later moved to Los Angeles as a youth with his family. He began his career as Jim Corbett's sparring partner in Reno in 1896 on the West Coast, managed by William A. Brady, Corbett's manager. He was a magnificent athlete. He was very fast and agile and in his prime, stood at 6'2" and 220 pounds. He could run 100 yards in eleven seconds and high jump 5'10", which were definitely feats in those days at the turn of the century (www.wbhf.org).

After a string of victories, Jeffries challenged Bob Fitzimmons for the heavyweight title at Coney Island, New York on June 9, 1899. Jeffries won by knockout in the eleventh round with a left-hook, right-uppercut combination (Robert Cassidy, pg.1). The training for this fight, with middleweight Tommy Ryan, is what developed Jeffries style. He boxed out of a crouch where he protected his face with his right forearm, and advanced with a probing left hit. His left hook was particularly effective when used from this crouching position (Robert Cassidy, pg. 1).

Jeffries officially announced his retirement from boxing in 1905. He was the first man to retire as an undefeated (18-0-2, 15 KOs) heavyweight champion (Robert Cassidy, pg.2).

In retirement Jeffries became an alfalfa farmer and bloated to more than 300 pounds. Jeffries had been asked to be the "white hope" to dethrone Jack Johnson. Although Jeffries had formerly refused to fight Johnson because he was black, Jeffries agreed in late 1909 to fight Johnson for the championship title the next summer at the age of 35. In training, Jeffries trimmed down to 227 pounds, seventeen off from his prime weight of 210.

George "Tex" Rickard, the greatest promoter in boxing history, won the bid to promote the Johnson-Jeffries fight. He had planned on it to take place in San Francisco in the summer of 1910. However, in June anti-boxing crusaders persuaded the mayor to refuse the fight to take place because of its controversial nature. Rickard then moved it to Reno, Nevada where a special arena was built and 30,000 fans of all races showed to watch the fight.

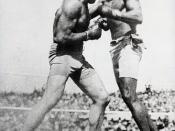

Johnson, who had knocked out Jeffries' brother in 1902, was wary of the former champion, Jefrries, in the first few rounds. He appeared physically fit, but it soon became apparent that Jeffries' six-year layoff from boxing had taken its toll. Johnson, 32 at the time, began to open up, but still remained cautious in the sixth round. Jeffries landed a few occasional blows, but they lacked his former championship ability. It is reported he told his corner, "my arms won't work, but just give me time and I'll be all right (www.ibhof.com, pg.2)." Johnson leaped from his corner at the beginning of the seventh round. He landed a hard right to Jeffries' jaw that visibly had effect. Johnson increased his tempo of attack and had peppered Jeffries with hard counter punches throughout the match. At the end of the seventh round Johnson sent Jeffries back to his corner with his right eye nearly swollen shut. In the fourteenth round Johnson sent Jeffries onto the canvas three times. This is the first time in Jeffries' career he had been knocked down (www.ibhof.com, pgs. 2 and 3). The fight ended in the fifteenth round with Johnson winning by knockout becoming the first black, and first Texan, to win the heavyweight boxing championship of the world.

Race rioting was widely sparked after the Johnson-Jeffries fight. African Americans struggled against efforts to contain the showing of the fight. Viewers in Harlem cheered during outdoor screenings despite efforts to keep the film away from African American audiences. Secret showings were often arranged in black neighborhoods. Finally, in 1912, Congress banned the interstate shipment of all fight films (www.sandiegohistory.net).

In 1913, Johnson was convicted of violating the Mann Act because of its specifications of transporting white women across state lines for prostitution. He jumped bail and fled to Canada. He continued his career and fought in England and France. In 1915, Johnson went up against Jess Willard, another "white hope," in Havana, Cuba and lost his title after 26 rounds. In 1920 he returned to the U.S. and served 1 year of his sentence. He died near Raleigh, North Carolina on June 10, 1946 in a car crash, having never regained his title. In 1954, he was elected to the boxing hall of fame.

Jeffries' one loss to Johnson forever damaged his career. He is mostly remembered for his one loss instead of his nearly undefeated career. Over time however, he has been recognized as the best defensive boxer in heavyweight history (www.ibhof.com, pg.3). He died in Burbank, California on March 3, 1953. Along with Johnson, Jeffries was also elected to the boxing hall of fame in 1954.