After the Barbarian Invasions and the fall of Rome in 476 AD, the church stood in power providing the Germanic tribes administrative and supernatural authority. The church had a major voice primarily in religious matters and to a lesser degree in secular affairs. During the Carolingian Empire, the church began to profit from land they acquired establishing the large monasteries and dioceses, and thus began to gain secular and worldly power. Emperors and kings tried to attach themselves to the wealth and authority ecclesiastical members possessed by offering the church protection in return. During the 11th century, the church argued with the state that lay princes could not participate in ceremonies that chose bishops and abbots who were installed in their dioceses. This was the basis of the Lay Investiture Controversy. As the church and its officials gained more power secularly, the power of the emperors who allied with them became jeopardized and eventually led to the collision between church and state over the fact that church would not let the emperor interfere in any religious matters.

During the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church gained power and prosperity and strengthened because of it. The church?s wealth included lands, from monasteries, and money, from the buying or selling of church offices, or otherwise known as simony. The wealth of the church led to the belief that it was corrupt and that there was need for reform. The emperor also had power, and during the Carolingian Empire and beyond, the power of the emperor strengthened. Emperors became accustomed to nominate bishops within their realm because bishops formed an important element of imperial government and the emperor was more concerned that they be loyal to him than that they be morally upright. This also was a basis that the church reformers said that caused the corruption in the church. As time went by, the corruption of the church became a major concern and strong reform groups began to form. Emperor Henry III was one of the first reformers, as he called synods, in 1046, throughout Italy, deposing three claimants to the papal throne and elevating Clement II, the first of a series of imperial appointees. This reform movement started by Henry eventually led to the power struggle between kings and popes. Probably the most influential reform group was the reform movement in Cluny, France known to history as the Cluniac Revolution. Cluniac monks sought to abolish all acts of simony and to end control of the church by laymen. Because of these reform movements, especially in Cluny, there became tension between the kings and churchmen over the issue of investiture by laymen in the 11th century. During the later part of the 11th century, successions of popes were inspired by the Cluniac reforms to seek greater independence for the papacy and church. Church officials thought that they had to perform the right ritual in order for the ceremony to be correct, and that laymen, like kings, were incapable of doing such a task. Officials also wanted to seek independence, because they thought that the sacred power should be higher than the secular power, and that the emperor should be ?subordinate to the religious order.? For example, Gregory VII stated that kings and princes got to be powerful by being ignorant to God and performing the Devil?s crime. This surely means that the secular leaders are subordinate to religious ones. Gregory VII also stated that lay domination of the Church was producing ?unworthy clerics, undermining clerical morality, and jeopardizing the salvation of Christians.? Secular leaders, such as Henry IV, responded by attacking the popes and questioning their ignorance of God and honor.

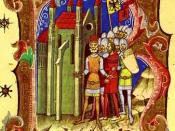

During the 11th and 12th centuries, a series of events led to a power struggle between popes and emperors based around lay investiture. The reform movements towards the church had two main goals. One was the freedom of papal elections with no interference from the emperor. And the other was the freedom from interference in ecclesiastical affairs by civilians. This included simony, something that was considered to be one of the main reasons the church was corrupt. In 1059, Pope Nicholas II issued Papal Election Decree condemned lay investiture and also excluded the emperor from participation in papal elections, a privilege given to emperors since Otto I. A synod also took the power away from the emperors and established a council of church officials, known as cardinals, to elect the popes. The greatest conflict in the lay investiture controversy occurred between the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII. In 1075, Pope Gregory VII forbade all lay investiture and ultimately forbade the practice of non-church officials installing churchmen in their religious offices. Henry IV reacted by having him deposed by a synod at Worms, Germany in 1076. Gregory VII responded by having Henry IV excommunicated, only to grant him forgiveness after Henry sought the pope out at Canossa in the winter of 1077. This angered the German nobles and they elected a rival king, Rudolf of Swabia. This led to civil war for many years to come. Eventually in 1080, pope recognized Rudolf as king and excommunicated Henry. Henry responded by deposing Gregory and electing a new pope as Clement III. After the death of Rudolf, Henry regained control of Germany and strengthened his forces leading them into Italy and capturing Rome, where he was crowned emperor by Clement. Gregory escapes and later dies in 1085.

After Henry was driven back to Germany, his sons turned against him and his son became Emperor Henry V. There were many ideas for solutions for the investiture controversy, but the interests of both the church and the king had to be met. The major interest of the church was to ensure that lay rulers would not give religious office. The essential interest of the kings was that bishops, who were also secular rulers, be made to recognize the authority of the king. In 1122, Henry V continued for supremacy over the papacy, but eventually made a compromise with Pope Callistus II on investiture. The agreement was the Concordat of Worms in 1122, which stipulated that the church was to have the right to elect bishops, and investiture by ring and staff was to be done by the clergy. It also stated that elections were to take place, however, in the presence of the emperor, who also would confer whatever lands and revenues were attached to the bishopric by investiture with a scepter, a symbol without spiritual connotations.

The pope probably got the better end of the deal, but the church never did obtain complete control over the nomination of bishops in the Middle Ages. The continuing rivalry between the empire and papacy contributed in many ways to the weakening of the emperor's authority and his powers. The emperors not only lost their dominance over the papacy but by giving up their ability to appoint bishops that would be loyal to them, had also gained more potential rivals. Even though there was still a limited role for the emperor in investiture, the shift towards a more independent church had become evident. The church gained dominance in peoples? lives spiritually and secularly throughout the Middle Ages and all the way up to the Renaissance.