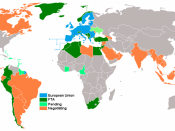

Economists are still unaware as to whether regional trade agreements and trade hinder or promote globalisation. Given that they can be inclusive or exclusive, offer reciprocal trade to other countries or set high tariff walls, it appears that many countries are seeking membership to avoid being the one left out. As the World Trade Organisation works towards achieving unilateral reductions in protection to maximise the benefits of trade, it seems that those countries that are gaining the most from international flows of goods are those who only trade with a select few.

With the increasing trend towards a global economy, countries are now forced to be not only regionally competitive, but also internationally competitive. The reduction of protection barriers such as tariffs and subsidies is providing serious challenges for less efficient producers to compete in the global market place. In an effort to provide increased trading opportunities and as a way of encouraging product specialisation, many countries have established trade alliances, signed trade agreements or become a part of trading blocs.

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) has actively encouraged such alliances and trade agreements, however, the WTO would see some trading blocs as anti competitive and are less inclined to favour these arrangements.

The vast majority of WTO member countries are party to one or more regional trade agreements. The emergence of trade agreements has accelerated since the early 1990's, with some 250 regional agreements notified to the WTO up to the end of December 2002. There are over 170 regional trade agreements currently in force and an additional 70 are estimated to be operational although not yet notified. By the end of 2005, if regional trade agreement's reportedly planned or already under negotiation are concluded, the total number of regional trade agreements in force might well approach 300.

The emergence of trade agreements and trading blocs can be directly attributed to the dawning realisation that we are all part of a global market place. Economies have become more integrated in recent years and have moved to target their most efficient industries as potential lucrative exporters. The result has been the formation of regional and global agreements that have allowed for expansion of industries and access to much larger markets.

Free Trade Agreements (FTA's) are formal arrangements between countries that allows for greater trading opportunities without the barriers often in place between competing countries. Such agreements made between two or more countries aim to encourage a policy of non-intervention by governments in trade between the participating countries. Tarrif and trade barriers are usually removed or significantly lowered between participating countries, while countries retain their own commercial policies when trading with non-members of the agreement. Australia has a long-standing free trade agreement with New Zealand called the Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (CERTA).

The CERTA agreement came into force in 1983 and was a positive initiative for both Australia and New Zealand. The results were the establishment of much closer trading ties and the opportunity to work on greater economies of scale in the areas of production, distribution and marketing. This agreement proved a decisive step for both economies as it lead to totally free trade between Australia and New Zealand, the elimination of all tariffs and quantitative restrictions and lower transaction costs. CERTA was designed to lower transaction costs associated with regional trade, creating a larger regional market and providing increased opportunities to achieve much more efficient economies of scale.

The benefits for both countries are easy to observe. Both countries have relatively small populations and they are both remote from the major markets of North-East Asia, North America and Europe, therefore access to wider markets even of a relatively small size provides great benefit to both countries. Australia is currently New Zealand's main trading partner in terms of imports and exports of goods and services. Australia is also the key destination and source when it comes to direct investment. Fifty-four percent of New Zealand's direct investment abroad is in Australia, and 36 percent of all foreign direct investment in New Zealand comes from Australia. Economically, our two countries are now enormously important to each other. Australia is New Zealand's largest trading partner and New Zealand is Australia's fourth largest trading partner. When speaking of this agreement in March 2003, Foreign Minister Alexander Downer stated that,

" In this 20th year of the CERTA - and 60th year of diplomatic representation - I take pride in how far our countries have moved towards economic integration and a single labour market. Australians and New Zealanders are no longer simply banking at the same banks, and driving the same cars. We are buying the same white goods, and the same foods."

Key features of CERTA are mutual recognition of goods and occupations. This means that any good sold in one country can legally be sold in the other and any official qualification obtained in one country is valid in the other. Another important issue of CERTA is the freeing of the labour market. This is recognised in the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement that allows Australians and New Zealanders to visit, reside and work in each other's country without restriction. The CERTA trade agreement is the most comprehensive bilateral trade agreement in existence and therefore, there is no doubt that this has had great benefits for the economic growth of both nations.

Free Trade agreements can be broken down into bilateral agreements involving two countries and multilateral agreements involving more than two countries.

A good example of a multi lateral agreement is The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This is an agreement signed between North America, Canada and Mexico and aims at a policy of non-intervention by the state in trade between nations. This agreement has resulted in lowered protection or no protection in the trade of goods and services betweens these countries. However each country still retains the same protection policy towards other countries that are not part of the trade agreement.

A Trading Bloc differs from a free trade agreement as such trading alliances organise a formal preferential trading agreement to the exclusion of other countries. Many economists argue that these trading blocs hinder globalisation and free trade as instead of making the world economies a global market, they create several larger markets. Trading Blocs can go one step further, forming economic unions. These are common markets where the level of integration is more developed and far more sophisticated. Member states that are party to such a union may adopt common economic policies e.g. the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the European Union they may have a fixed exchange rate regime such as the ERM of the EMU and they may even decide on a single common currency. The ultimate act of integration is likely to be some form of political integration, where some form of over-arching political authority replaces national sovereignty.

The European Union (EU) is the largest common market place in the world. This union was created as a result of The Treaty of Maastricht (1992) and introduced new forms of co-operation between the member state governments - for example on defence, and in the area of justice and home affairs. By adding this inter-governmental co-operation to the existing community system, the Maastricht Treaty created the European Union (EU). The EU is an economic union comprising of 25 European states and is the world's biggest trader. The EU generates one quarter of all global wealth and is now recognised as the largest trading bloc in the world. The EU was originally formed to avoid a repeat of the world wars. It was thought that if countries were closely integrated economically, a world war that would cripple the financial sector would not be repeated.

A single market for goods and services was formed in 1992. The Euro is the currency of twelve European Union countries, stretching from the Mediterranean to the Arctic Circle (namely Belgium, Germany, Greece, Spain, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal and Finland). Euro banknotes and coins have been in circulation since 1 January 2002 and are now a part of daily life for over 300 million Europeans living in Europe.

The EU's common trade policy operates at two levels. Firstly, within the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the European Union is actively involved in setting the rules for the multilateral system of global trade. Secondly, the EU negotiates its own bilateral trade agreements with countries or regional groups of countries. The EU and its predecessor the European Common Market have had significant impact on Australia's trading fortunes. Before Great Britain joined the Common Market, she was Australia's number on trading partner, particularly in Agriculture. This changed dramatically with Britains entry into the EU, where its commitment was required to member countries. This policy, known as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) also has a trade distorting effect on world markets because of its use of production and export subsidies

The emergence of trading blocs, such as the EU brings into question the value of free trade. Ross Gittins, the Sydney Morning Herald's Economics Editor, believes that all countries, including developing nations can benefit from lowering tarriffs and participating in free trade. In an article on the 19th June 2004, he stated that,

The World Bank estimates that developing countries stand to realise gains worth $US31 billion ($45 billion) a year if other developing countries eliminate their tariffs on manufactures, and a further $US31 billion a year if they remove their barriers to agricultural trade.

If implemented in a fair and equitable way, free trade can maximise output by insuring efficient allocation of resources on a global scale. It also enables countries to enjoy goods that they can't produce themselves, because of inept industry or geographical factors, and so add value to lifestyle and economic benefit. The benefits of free trade can create a "level playing field" for international trade. A significant benefit is the increased utilisation of economies of scale. As trade increases so does the size of a firms market, leading to improved allocation of resources through specialisation. Resources that are inefficiently allocated, or industries that are no longer profitable are forced to re-examine their future directions. To insure international competitiveness costs must be kept to a minimum as now the consumer has sovereignty and access to lower prices. To provide he quality at a competitive rate new technology often emerges, keeping production processes efficient and improving the quality of goods. As direct consequence of efficient allocation of resources, economic growth occurs and the result is inversed real incomes and increased living standards.

Perhaps the greatest challenge the world faces on globalisation is ensuring it works to the benefit of the developing countries. The UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan stated in June 2004, that the lack of a development-friendly trading systems is one of the main factors hindering the integration of developing countries into the global economy. It may be that for poorer nations, trade blocs are a medium term solution to their inability to be part of the level playing field at present. They certainly can't enter into a free trade environment without the support of the richest countries, the United States, the European Union and Japan. It is only be agreeing to make the international trading system more development friendly and agreeing to significant reductions in agricultural protection that the more affluent nations provide acces for developing countries to the global market.

In the interim period, the establishment of trade blocs comprised of developing nations may provide a short term solution. In a recent report, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade's Economic Analytical Unit pointed out that developing countries have a lot to gain by increasing the trade between themselves. There's no reason why developing countries shouldn't make themselves mutually better off by increasing the trade between themselves. About half of the developing countries' exports of textiles go to other developing countries, and a fifth of their exports of clothing go to other developing countries.

From an international perspective, it would seem that the world is increasingly dividing into trade blocs. The world's two most powerful economies, the United States, and the European Union, have each tried to forge links with neighbouring countries and block access to rivals. Other major trading countries, like the fast growing exporters on the Pacific Rim and the big agricultural exporting nations, have also tried to create loose trade groupings to foster their interests. This is providing economists and world leaders with great challenges. The major issues facing the world trading system revolve around whether the increase in trade blocs will lead to increased protectionism, or the promotion trade liberalisation.

We are yet to discover the benefits of free trade compared to the establishment of regional trade agreements or trading blocs. It may be that with current trends in world economics, we may never see free trade totally implemented. Rather we may live in a world of competing trading blocs, bringing prosperity and increased market share on a regional rather than a global basis.