Tommy is in his room reading his homework and trying hard to pay attention. His mom, Janet, has walked by three times in the last fifteen minutes; each time catching him not doing his work, but staring into space or playing his video games. She's been aware of his short attention span since he was in kindergarten, but she always figured it was a typical problem for kids his age. But now he's in third grade and the problem hasn't gone away. His teachers have started calling Janet and complaining about his hyperactivity during their lessons. "He refuses to raise his hand and has problems sitting still for longer than five minutes," Mrs. Hopewell told Janet one Monday night. Janet is worried that Tommy may have Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), but she is reluctant to have him put on drugs for it.

Tommy's situation isn't abnormal.

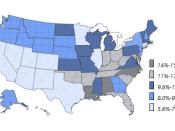

In fact eight percent of children in North America have been diagnosed with ADD and are prescribed drugs. In Canada the number of children diagnosed between 1991 and 1997 increased from 205,000 to 561,000 (Donnely, 1). It is believed by scientists that ADHD occurs when receptors in the brain do not react to the brain's natural chemicals, such as dopamine and norepinephrine. These receptors are engaged in focusing concentration and controlling impulsiveness (Brink, 3).

ADHD started being recognized as a problem in the 1950's. In 1968 the disorder was called Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood Disorder with symptoms such as short attention span, and over activity. In 1980 the name was being called Attention Deficit Disorder (with or without Hyperactivity). Yet again the name was changed in 1987 to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Finally, in 1994, ADHD was introduced having three subtypes: Inattentive, Hyperactive/Impulsive and Combined Type (Dalsgaard, et...