Shoeless Joe Jackson Joseph Jefferson Jackson was born on July 16, 1889, in Greenville, South Carolina. His parents were George Elmore and Martha Ann Jackson. Martha Ann was a big woman with jet-black hair who loved to cook. George Elmore was a thin, tall man, who loved to farm. Joe was oldest of the eight children. He had five brothers whose names were David, Jerry, Earl, Ernest, and Luther. His twin sisters, Martha Andre and Annabel, were both the babies of the Jackson family. In spite of the fact that the whole families were baptized Baptists, they very rarely practiced religion.

In 1895, when Joe was six, the Jackson family moved to Brandon South Carolina. There, George Jackson got a job at the local mill, he never had any form of formal education. He was born illiterate and remained that way all throughout his life. Paralleling this time period, was the introduction of the National League roster of eight teams.

They were Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Cincinnati, New York, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and St. Louis.

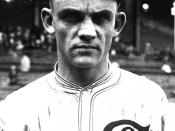

In 1902, when Joe was 13 he worked a 12-plus hour day in the local cotton mill with his father and one of his brothers. It was then he was first presented to the sport of baseball. He was given the opportunity to play on the "Textile League"ÃÂ and a sense of belonging. On Saturday afternoons, the team played from town to town, bringing prestige on to their company. When Joe was 15, he was given his first bat of his own which he named "Black Betsy."ÃÂ He was then traded to a Near Leaguers team, which was semi-pro. By this time, he had two passions: baseball and a girl four years younger, Katie Wynn.

He began his profession career in 1908, with a home run, a triple, and a double, batting third and playing center field. In May, he was batting .350 and was engaged to Katie Wynn. Later in this season and after the marriage took place, June 19th, Joe Cantillion, the former manager of the Washington Senators said Joe "is simply a bush leaguer flash in the pan and will prove a force in the big leagues"ÃÂ (Frammer 13.) There are many theories of he gained the nickname "Shoeless Joe"ÃÂ but nevertheless he was a baseball myth of fact and fantasy. The theory of Connie Mack, the commissioner of baseball at the time is, "An apothecary down in Pittsburgh who had previously written me some good tips in regard to young prospects, kept urging me to give this fellow a try, but what intrigued me the most about this prodigy is that he played without shoes. "ÃÂHe doesn't even wear spikes or in fact anything covering his feet' came the tip. "ÃÂHe's so fast that he can tear around those bases without any such help. They call him Shoeless Joe.'"ÃÂ (Hayes 14) Another theory arises from a game in South Carolina where Joe was called in to pitch a game. The next day his feet were sore from pitching, and when it was his turn to bat, he slipped off his shoe and stepped into the batter's box. He slammed a home run. As he rounded third base, a fan shouted, "You shoeless son of a bitch!"ÃÂ And the name shoeless just stuck, according to Carter Catimer (Frammer 14.) It doesn't really matter which way he got the name, Shoeless Joe is a baseball great. He was offered a chance to be educated during the off season, but he refused. He said, "It don't take none of that school stuff to help a fella play ball"ÃÂ (Frammer 21.) After a while Joe was sent to Cleveland, his illiteracy was widely known around baseball and the subject of laughter. He was often teased with the same line, "Hey, Joe can you spell cat?"ÃÂ But besides this set back, he batted .356. Ahead of him was Ty Cobb in second with .367 and first was Roger Hornsby with .385.

While Joe's success increased, his wife a business manager and tutor, devoted countless hours to tutor Joe. He tried patiently to learn, but all he had ever written still was an abstract design for a signature. In 1911, even with Joe, Cleveland had no chance at the pennant. He contributed his hardest with 233hits, 45 of them doubles, 19 triples, and 7 home runs and a batting average over .462 at July fourth, what is now the All-Star break. Shoeless was voted rookie of the century. When Babe Ruth made his debut against Cleveland, Jackson hit a three-run triple off of him. The Great Bambio admired Joe and said, "I copied Jackson's style because I thought he was the greatest natural hitter I ever saw, He's the guy who made me a hitter"æ"à(Miller 405.) In 1915, he was traded to the Chicago White Sox who he made his World Series debut for, two years later. His performance was good, but not sensational. Unfortunately, with the unset of World War I, he was found eligible for military service. He was able to escape, but was forced into wartime industries. Without Joe on the team, the White Sox had no shot at the Series in 1918. The following year, however, he was back on the team and ready for anything. The Sox won the pennant and were to face Cincinnati in the World Series Gossip arose of a fixed World Series betting pool, but it seamed to be impossible for all 18 of the men to be paid off. Chick Gandil reportedly told Joe, "Seven of us have gotten together to frame the World Series. You'll get $10,000 if you help us out"à(Frammer 96.) Jackson didn't want anything to do with this and begged to be taken out of the line-up. He informed the head coach about the scandal, but he wouldn't listen.

The first game Joe went 0-4 and Chicago lost 9-1 to the Reds. Joe tried harder in the second game getting a double, the first of three hits, but again Chicago lost 4-2 and more talk arose of a fixed Series. In there home field, Joe improved and the Sox won 3-0. The fourth game is where evidence of scandal arose. There were two field errors and a ball that could have saved a run, thrown by Jackson, was intentionally cut off. The next game was a three-hitter, all by Jackson, and the Reds led the series 4-1. The Sox won their second game 5-4. The final game, game eight, Chicago lost 10-5, losing the Series for the Sox. Joe had batted .375, had 12 hits, made no errors, and hit the only homerun of the series.

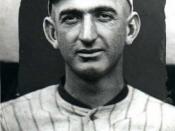

After the final game, Joe was handed a dirty envelope with $5,000 inside. The World Series had been sold to a gambling group. Joe didn't want the money, threw it down and walked out. News of the scandal was more and more evident, and the players paychecks were withheld, until information was discovered. Comiskey paid detectives to discover what had happened in the series. Joe was named in the confession along with the gamblers made by Cicotte.

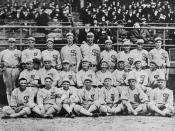

A Grand Jury Trial was carried out and although Joe testified to have nothing to do with the scandal, and in truth didn't he was one of the players who had charges brought against him. They were Felsch, Gandil, Williams, Risberg, McMullin, Weaver, Cicotte, and Jackson. They were found guilty and sentences an indefinite suspension of Chicago baseball team and retired from organized baseball for the rest of your lives. From then on their team was referred to as the 1919 "Black Sox"ÃÂ for all of history.

This team scheduled an illegal game that was never to be played. They all were informed to leave Illinois and all did. The investigation continued into 1921, where Joe was found not guilty, but was still banished from baseball and had his dignity raped. Joe was 33 and in his career prime, but was never to play again.

Despite his feelings, in 1942, they had a Joe Jackson appreciation night, where they honored him as a legend of baseball. Joe was name the all-time best natural hitter. Joe was scheduled to make an appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show on December 16, 1951, but he never made it. He dies, December 5th, 1951 in Greenville, South Carolina, from a massive heart attack. His dying words were, "The good Lord will know I am innocent. Good-bye, my fans, this is it"ÃÂ (James 181.) Joe was one of the "eight men out"ÃÂ never admitted in the Hall of Fame, but their manager Charles Comiskey was admitted into the Hall of Fame and has a Stadium named in his honor. He became the White Sox legend that Shoeless Joe should have been, but never had the chance.

Bibliography Frammer, Harvey. Shoeless Joe Jackson and Ragtime Baseball. Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1992.

Hayes, Jenner. "Shoeless Joe Jackson,"ÃÂ Great Athletes Vol. 8. Californian: Magil Books, 1992: 1174-1196.

James, Bill. "The Teens,"ÃÂ The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Villard Books, 1986.

:Joe Jackson's Life"ÃÂ Microsoft, Encarta 96 Encyclopedia. 1996: (CD ROM).