�PAGE � �PAGE �7�

THEORETICAL GRAMMAR

Introductory to the theoretical study of the English Language Grammar

1.1. The Subject of Theoretical Grammar.

1.2. Kinds of Theoretical Grammar.

1.3. Main grammatical notions:

1.3.1. Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations.

1.3.2. Grammatical categories.

1.3.3. Language levels.

1.4. General characteristics of the contemporary English language system.

The Subject of Theoretical Grammar

Theoretical Grammar is a section of linguistics that studies grammar system of language.

Grammar system of language refers to the whole complex of conformities to natural laws where the latter defines ways of words' alterations and also ways of word combinations in phrases and sentences.

As any complex object Grammar is a complex system that is presented by elements and structure in their mutually dependent organization.

Grammar elements refer to morphemes, words, word-combinations and sentences.

Grammar structure implies relations and connections among grammar elements or inner organization of the language grammar system.

The subject of English Theoretical Grammar refers to the study of the English Language grammar organization as a system parts of which are mutually connected with definite relations of different types of complexity (complication, complicacy).

The main task of Theoretical Grammar is an adequate systematic (methodic) description of language facts and also their theoretical interpretation.

The difference between Practical and Theoretical Grammar refers to the following peculiarities:

Practical Grammar prescribes definite rules for the use of a language (gives instructions for the use of language data, teaches how to speak and write);

Theoretical Grammar analyzes language data, interprets that, expounds the data but does not give instructions as for the use of them.

Kinds of Theoretical Grammar

To explain and interpreter a phenomenon means to reveal and understand its nature. Kinds of Theoretical Grammar are defined by different approaches to the problem of How to interpret language data.

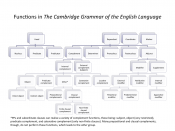

In accordance with an approach there is a kind of Theoretical Grammar (Drawing 1.1).

Drawing 1.1. Basis for approaches to the problem 'How to interpreter language data'.

The drawing 1.1 shows relations of language signs with other different phenomena, which grounds the appearance of the approaches to the interpretation of their relations (table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Theoretical approaches to language data interpretation

Type of relations (drawing 1.1) | Essence | Approach | ||

A language sign - other language signs (1 - 2) | Relations among language signs | Combinations of syntagmatic elements | Distributive Grammar | Structural or Formal Grammar |

Alterations of grammatical forms | Transformative Grammar | |||

A language sign - a notion (2 - 4) | Connections between grammatical categories and categories of thinking | Logical Grammar | Semantic Grammar | |

The speaking - a language sign (5 - 2) | Influence of psychology on the use of grammatical forms | Psychological Grammar | ||

Language signs - references (2 - 3) | Relations of language signs and non-language objects that are marked with language categories and grammatical forms | Grammar of Situation |

Thus, there are two general approaches - pure linguistic and semantic. To the former Structural or Formal Grammar is referred, and to the latter - Logical Grammar, Psychological Grammar and Grammar of Situation (drawing 1.2).

It tends to comprehend and explain all phenomena of language by inner relations among signs: relations among syntagmatic elements (Distributive Grammar), connections of different forms of language signs (Transforming Grammar) without addressing to neither thinking nor objective reality or psychology of the speaking. | These types tend to comprehend and explain language data by their relations with non-language phenomena (thinking (Logical Grammar), peculiarities of individual and group psychology (Psychological Grammar), peculiarities of grammatical forms choosing for objects and natural phenomena naming (Situated Grammar) |

Drawing 1.2. Two general types of Theoretical Grammar

Inside of each approach there are static (gives a way to make language facts be brought to light and classified) and dynamic methods (searches how one language facts transfer into other and one grammar forms appear from others) of language data study.

Main grammatical notions

1.3.1. Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations.

As for the structure Theoretical Grammar can be stipulated by syntagmatic (distributive) or paradigmatic (transformative) relations.

Other words, connections of language elements can be syntagmatic or paradigmatic (drawing 1.3).

Relations of contiguity The relations stipulate connections of language elements of the highest level. Adjacent language elements (relations of contiguity) can not replace each other for they belong to the different grammatical categories. They create meaningful combinations and have a propriety to combine meaningfully (not any two or more elements can be combined). * A combination of sounds creates a morpheme (a) or even a word (b). For instance: a) [p] + [r] + [i] = [pri] (the prefix 'pre' that means 'before or preceding sth'); b) [t] + [i] + [n] = [tin] (the word 'tin' that means 'a chemical element, a soft silver-white metal'). BUT the sounds [p], [r], [t], [n], for example, together will not create any meaningful combination (the same - in the brought under examples). * A combination of morphemes creates a word. For instance: the prefix 'in' (here = 'not') + the root 'explic' (from 'explicit' = 'clear') + the suffix 'able' (= 'can') = the word 'inexplicable' ('that cannot be understood or explained'). * A combination of words creates a phrase (a) or a sentence (b). For instance: a) the article 'a' + the noun 'pint' + the preposition 'of' + the noun 'milk' = the phrase 'a pint of milk'; b) The pronoun 'She' + the auxiliary 'has' + the notional verb 'come' = the sentence 'She has come'. | Relations of similarity The relations unite language elements that cannot become adjacent but can replace each other. They belong to a class of elements that has a general similarity and forms paradigmatic series. For instance: a) in the given under varieties of a phrase pint a cup of milk bottle gallon the words 'pint', 'cup', 'bottle', 'gallon' are included to the series of language elements which means some quantity of a liquid and can replace each other in accordance with the quantity that is meant. Thus, the words form a paradigmatic line of language elements; b) in the given under sentences Jack is sleeping. Jill is reading. predicates can replace each other in accordance with a real situation, too: Jack is reading. Jill is sleeping. Though they cannot be adjacent. It is impossible to use them adjacently: Jack (Jill) is sleeping, reading. It is incorect use that has no sense. Thus, the predicates 'is sleeping' and 'is reading' form a paradigmatic class of predicates and the proper names 'Jack' and 'Jill' - the one of subjects. c) the given under forms of the verb 'mean' mean, meaning, meant, has meant, is meant, had been meant, meaningful, etc. also create a paradigmatic line of forms that are variants of the word 'mean'. |

Drawing 1.3. Two general types of structural relations of language elements

1.3.2. Grammatical categories.

To the main notions in the study of Theoretical Grammar the following ones are included: grammatical category; grammatical form and grammatical meaning.

Grammatical Meaning differs from Lexical Meaning. The latter implies an idea or a sense that a word represents. Grammar Meaning also implies an idea or a sense but they (idea\sense) are peculiar to a class of words but not to a single word; they are united by a general propriety of the class of words. Thus, Grammatical Meaning is a generalized or abstract propriety of a class of words and unites big groups of classes of words.

For instance:

Class of words | Proprieties |

The Noun | to present objects or things (abstract or concrete). |

The Verb | to express action. |

The Adjective | to show a sign or a quality of an object or a thing. |

So, the Grammatical Meaning of the Noun is the propriety to present objects or things, the one of the Verb is the propriety to express an action, the one of the Adjective is the propriety to present a sign or a quality of an object or a thing, etc.

Grammatical Meaning is expressed through the formal indices of a class of words or through their absence. Formal indices are specific for each language and express Grammatical Meaning only when they are joined to the stems of definite parts of speech.

For instance:

The index 's' in the English Language can express:

the Plural form of the Noun (a language - languages);

the Present Simple for the 3rd Person Singular (We live. - He lives.);

the Possessive Case of the Noun (a friend's advice).

Grammatical Form refers to a material expression of Grammatical Meaning (expression of a word's form or inflexion).

For instance:

The Grammatical Form 'has been speaking' is a material (language) expression of the Grammatical Meaning of the Verb which is presented by the definite notional verb 'speak' in the Present Perfect Continuous which refers to the 3rd Person Singular.

Grammatical Category appears on the ground of Grammatical Forms (that in their turn express Grammatical Meaning); it cannot include less than two opposite or properly correlated Grammatical Forms.

For instance:

In English there are:

the Category of Tense (Past, Present and Future) that includes 3 Grammatical Forms (properly correlated);

the Category of Aspect (Simple, Continuous, Perfect Simple and Perfect Continuous) that includes 4 Grammatical Forms (properly correlated);

the Category of Voice (Active and Passive) that includes 2 Grammatical Forms (opposite);

the Category of Number (Singular and Plural) that includes 2 Grammatical Forms (opposite), etc.

Grammatical Category presents a peculiar reflection of reality as the Category of Tense, for example, reflects a relation of an action to a moment of time; the Category of Voice reflects a relation of an agent to an action, etc.

Grammatical Category refers to the unity of two or more Grammatical Forms that are opposite or brought into proper correlation in accordance with Grammatical Meaning (example given above).

1.3.3. Language levels (table 1.2)

Table 1.2

Subdivision of Language Levels'

Language Levels | Unites | Essence |

1. Primary | Basis of elements (conditional statics): | |

Phonemic | Phoneme (sound) | Phonemes build material form for language signs but are not material signs by themselves. They form morphemes. |

Lexical | Lexeme (word) | Words and steady expressions |

Proposemic (ÿÃÂþÿþ÷õüðÃÂøÃÂõÃÂúøù) | Phraseme (phrase) | Sentences |

2. Transitive | Transition of elements (conditional dynamics): | |

Morphemic (üþÃÂÃÂõüðÃÂøÃÂýÃÂù) | Morpheme (building element of Word) | |

Denotative (ôõýþÃÂðÃÂøòýÃÂù) | Denoteme (Categorematic Word or Phrase) | from a word to a sentence |

Dictumic - from dictum['diktem]: a statement that expresses sth that people believe is always true or should be followed - (ôøúÃÂõüðÃÂøÃÂõÃÂúøù) | Dicteme (sentence or contextual thematic unite of sentences) | from a sentence to a text |

Certain units are defined by inner, relatively reserved in a corresponded level features. To such unites the following are referred:

Phoneme which is defined with a set of phonologic distinctive signs and which is not marked with the function of a sign;

Word which is defined with the signs of nominative function;

Sentence which is defined with the signs of predicative function (table 1.2).

The quality of other units is distinguished in a necessary and ingenious correlation with the units of adjacent levels. They are

Morpheme which is defined as a component of a word (with its nominative function of a sign);

Denoteme which is defined as a component of a sentence (with its situation-predicative or propositive function);

Dicteme which is a component of a text (with its communicative funtcion) (table 1.2).

General characteristics of the contemporary English language system

All languages are classified on the ground of two basic principles - of their genealogy (origin and relations) and of their typology (structure).

Typological classification is one which is based on the distinguishing similarities and differences of the structures of languages independently on their affinity. It is also called Morphological classification as it studies forms, structures and 'building' components of languages.

Typological classification was firstly worked out, grounded and proposed by the brothers August and Fririch Sleggel (XVII/XIX). They distinguished inflectional (ÃÂûõúÃÂøòýÃÂõ), which have inflections, and non-inflectional (ýõÃÂûõúÃÂøòýÃÂõ), which do not have inflections, languages. Besides, they distinguished synthetic (earlier) and analytical (later) languages (Drawing 1.4).

V.Gumboldt (XVII/XIX) reworked the Sleggels' classification and distinguished four types of languages: insulating (ø÷þûøÃÂÃÂÃÂÃÂøõ øûø úþÃÂýõòÃÂõ), agglutinative (ðóóûÃÂýðÃÂøòýÃÂõ), incorporated (øýúþÃÂÿþÃÂøÃÂÃÂÃÂÃÂøõ) and inflectional (ÃÂûõúÃÂøòýÃÂõ).

Insulating languages do not have affixes and express grammatical meanings with adjoining of certain words to others with the help of Syntacategorematic (auxiliary) words. There is no difference between root and stem in such languages. Words do not change and consequently do not have any indices of their syntactic correspondence with other words. The main means of syntactic combination is adjoining. Sentence, thus, is a definite sequence of unchangeable and indivisible words-roots.

For instance:

Chinese, Vietnam, Tibetan, etc.

Chinese:

Ma - mother

Ma - hemp

Ma - horse

Ma - to scold at

Ma ma ma. ÃÂðüð ÃÂÃÂóðõàúþýÃÂ.

Ma ÃÂø üð. ÃÂðüð õôõàýð úþýõ.

Agglutinative (glutten (Latin) - glue, agglutino - to glue) languages are the ones in which grammatical meanings are expressed with special affixes - 'stickers'.

For instance:

Turkish, Georgian, Japanese, etc.

Turkish:

Lar - Plural form

Da - Prepositional (ÿÃÂõôûþöýÃÂù) case

Masa - a table

Baba - a father

Masada - on the table

Masalar - tables

Masalarda - on the tables

Babada - on the father

Babalar - fathers

Babalarda - on the fathers

Incorporated (incorporatio (Latin) - including, joining to a set) or polysynthetic (polys (Greek) - a lot of, synthesis - joining up, association, formation) languages are those in which different parts of an utterance present amorphous words-stems (words-roots) which are incorporated into united complexes number of which, in their turn, are formed with auxiliary elements.

For instance:

Majority of the languages of South America, ÃÂÃÂúþÃÂÃÂúøù

çÃÂúþÃÂÃÂúøù:

óð - üð - a kind of the case which shows a sign with whom or with what

óðÿojóeüð - with a spear

óðÃÂþÃÂÿojóeüð - with a new spear

óðÃÂðýÿojóeüð - with a good spear

óðÃÂðýÿõûwõýÃÂõÿþjóeüð - with a good metal spear

Inflectional languages express their grammatical meanings mainly with inflexions.

They are divided into synthetic and analytical.

Grammatical relations of words are expressed by the forms of these very words. A meaningful word alters and presents its new forms to express grammar relations For example: Russian, Ukrainian | A meaningful word is not able to alter. For that other words are used - auxiliaries. They help to express grammar relations or combine words in phrases or sentences. Peculiarity: auxiliary element (auxiliary verb) does not have a lexical meaning; notional verb does have that. For example: English, French |

Drawing 1.4. Division of languages as for the systems of changes of their grammar forms

(synthetic languages and analytical)

Old English used to be a synthetic language and used to have its own system of inflections. Though with the time (foreign intrusions, wars, cultural ties) it altered and transformed into an analytical one. Nevertheless in English some synthetic forms are still used (look for example of the 2nd characteristic of English brought under).

Characteristics of English:

Auxiliaries. Auxiliary verb does not have a lexical meaning; notional verb has that.

For instance:

She has already been preparing for three hours (both auxiliaries - has been - do not have lexical meanings) = ÃÂýð óþÃÂþòøÃÂÃÂàÃÂöõ ÃÂÃÂø ÃÂðÃÂð.

She has a nice kid (has is not an auxiliary but a notional verb here, so it has a lexical meaning to obtain, to posses sth) = ÃÂýð øüõõàüøûþóþ ÃÂõñõýúð = ã ýõõ õÃÂÃÂàüøûÃÂù ÃÂõñõýþú.

Scarcity of flexible forms.

For instance alterations:

a) of the Noun (Singular and Plural forms): a chair (Sng) - chairs (Pl);

b) of the Verb (in accordance with Tense, Person, Number): we approach (Present Simple, Plural), he approaches (Present Simple, Third Person Singular), we, he, etc. approached (Past Simple);

c) of the Adjective (Degrees of Comparison): pretty (Neutral) - prettier (Comparative) - the prettiest (Superlative).

Homonymy (which refers to the phenomenon of similar spelling or pronunciation of words that have different lexical meanings).

For instance, homonymy of Grammar affixes:

Boys study (Plural, Nominative Case) - boy's book (Singular, Possessive Case) - boys' book (Plural, Possessive Case).

Absence of Grammatical Agreement of a noun and an adjective that attributes the noun.

For instance:

A big boy (he) \ girl (she) \ apple (it). Compare with Russian ñþûÃÂÃÂþù üðûÃÂÃÂøú, ñþûÃÂÃÂðàôõòþÃÂúð, ñþûÃÂÃÂþõ ÃÂñûþúþ.

Use of the Noun in the Common Case as a prepositional attribute.

For instance:

Table (noun) + lamp (noun) = table lamp (table is a prepositional attribute).

Formal double complete predicative center (when a verb obviously has a personal form).

For instance:

Compare: It is dark. and âõüýþ.

Wide use of the assistant words.

For instance:

The Noun: one, they, that, this, those, etc.

The Verb: do, get, etc.

Wide development of secondary predicative combinations.

For instance:

Complex Object: They expected me to behave as they wanted but I was not going to allow them to manipulate me.

Direct word order.

For instance:

I have already been there.

Yesterday we gave him a book.

�

II Structure of the Word. Problem of Parts of Speech

The notions of the Word and the Morpheme.

Principles of subdivision of parts of speech.

Classification of parts of speech.

Theory of the field structure of the word.

2.1. The notions of the Word and the Morpheme

The word morphology is based on the two Greek words morpheme and logos.

Morpheme means form.

Logos was regarded as one of the main notions of the Old Greek philosophy. It meant both: 1) word (expression, sentence or speech) and 2) sense/meaning (notion, judgment or base). To the Old Greek philosophy it was introduced by Heraclites in the 6th - 5th centuries B.C. Logos (Mind) and Spirit (Soul) were considered as the base of the World's Fire or the initiation of Existence (Life).

Thus, it is seen that morphology in Linguistics does not only refer to the Form but also takes into consideration the Content.

To simplify, Morphology studies morpheme and word which is built with morphemes and can change due to them.

Morphology refers to:

A part of the system of language, the system of parts of speech, their grammar meanings, categories and forms of the Word.

A section of Grammar that studies such part of the language system; a science about parts of speech, their grammar meanings, categories and forms of word.

Word (general definition) is the main unity of morphology; a unity of language that denotes/names a definite object, thing, phenomenon or notion.

The definition of the Word, which is characteristic for flexible languages (given by Maslow, a professor, Leningrad school):

Word is a minimum unity of a language whose property is a positional independence (the examples are given under). It has characteristics of mobility (different words-parts of speech take different positions in a sentence) and discrete (can exist separately unlike/in the contrast to the Morpheme that has a meaning but cannot exist separately).

For example:

Respect is a desirable attitude (subject).

He has been paid a lot of respect (object). positional independence and mobility

We respect him (predicate).

When the word respect is said or written or heard it can exist separately and be perceived and understood (discrete).

Morpheme is a minimum meaningful unity of word that does not have a positional independency (prefix takes the position in the beginning of the Word, root takes main central position in the midst and suffix - at the end). Thus, all the morphemes can be divided into two big groups, root morphemes and affixes (table 2.1).

�

Table 2.1

Kinds of Morphemes

Kinds of Morphemes | |||

Root | Affix (prefix, suffix) | ||

Inflective | Word-formative (derivational) | ||

E S S E N C E | Is a part of a word which does not change and is always presented in any form of the word. For example: Black, blackish, blacken. Black is a root morpheme. | Serves to change the form of the same very word. For example: 1) I always invite him. He invites me. I invited him yesterday. 2) A boy - boys. | Serves to form new words. For example: Resist (action), resistance (phenomenon), resistant (characteristics), resister (person), resistor (thing), resistible (quality), irresistible (quality). |

NOTE! In English the Root coincided with the Stem. Stem is also regarded to be a root morpheme. Stem is a significant unity of Morphology, a part of the Word till the Ending.

In a language Morpheme is presented by its versions, allomorphemes (ðûûþüþÃÂÃÂÃÂ, from the Greek allo = other/another).

Characteristics of allomorphemes:

1) they have language (they mean sth, they form words' forms) and phonetic (they sound) power;

2) the allomorphemes of a definite morpheme can absolutely coincide in pronunciation

For example:

Fresh, freshment, freshen. The letters s,h in the root morpheme fresh create the same sound [ ].

3) the allomorphemes of a definite morpheme can be not identical in pronunciation

For example:

1)

Dreamed [d] the morpheme-suffix ed means the same - it is the index of Past Simple or

Loaded [id] Past Participle for regular verbs

Worked [t] but is pronounced differently

2)

Physics [k]

Physicist [s] in the root morpheme physic the letter c is pronounced differently

Physician [â¦]

2.2. Principles of subdivision of parts of speech

The whole structure of Language is divided into lexical-grammatical classes or parts of speech.

Different linguistic schools ground different ways of lexical-grammatical classes' subdivisions.

1.Henry Sweet (19th century), an English linguist

First scientific grammar of English (the second half of the 19th century);

Classical Grammar

Principles of classification:

1) the Form (morphological);

2) the Function (syntactic).

In accordance with the principle of Form he singles out two big classes - declinable (those parts of speech that can change their forms) and indeclinable (those that do not change).

There were singled out three subclasses of declinable parts of speech:

1) Noun-words (Nouns);

Noun-numerals (Cardinal Numbers (úþûøÃÂõÃÂÃÂòõýýÃÂõ));

Noun-pronounce (Personal and Indefinite Pronouns);

2) Adjective-words (Adjectives);

Adjective-pronouns (Possessive Pronouns);

Adjective-numerals (Ordinal Numbers(ÿþÃÂÃÂôúþòÃÂõ));

Participle;

3) Verbs (Finite and Non-finite verbs).

In accordance with the principle of Function he takes into consideration syntactic position that a definite part of speech can take in a sentence. He made an attempt to classify parts of speech in accordance with their syntactic function.

BUT the principle of Meaning was not distinct (clear) or was not taken into consideration at all. H.Sweet did not really take into account categorical parts of speech, properties of parts of speech to present generalized meanings (Grammar Meaning), for example, the property of the Noun to present objects and things, the one of the Verb to present action, etc. These properties he refers/relates/attributes not to the grammar ones but to the logical signs.

2. Jence Otto Harry Jespersen (1860-1943), a Danish linguist

Philosophy of Grammar (1924)

Made an attempt to reconcile/balance the principle/sign of the Form (Morphology) and the one of the Function (Syntax).

Principles of classification:

1) the Form (traditional description of parts of speech in accordance with their morphological form and lexical meaning);

2) the Function (analysis of the same singled out classes (above) in accordance with their syntactic function in an expression or in a sentence).

Created a theory of three ranks/classes (table 2.2), and by the theory made an attempt to give a generalized common classification of parts of speech based on the Function of the Word in Language Units more than a word (expressions and sentences).

Table 2.2

The essence of the Theory of Three Ranks

Ranks | Word | ||

Primary | Secondary | Tertiary | |

Essence | The main word in an expression | A word that directly defines a primary word | A word that subordinates to a secondary word |

Patterns | A dog | A barking dog | A furiously barking dog |

BUT morphological classification, syntactic function and theory of three tanks used together bred some confusion.

For example:

In the expression a dinner table the word table is regarded as a primary word.

Though in an expression a table lamp the word table becomes a secondary word.

3. Charls Freez (19th-20th century), an American linguist

The Structure of English

The main principle of classification:

Position of a word in a sentence (Syntactic Function) can indicate a Part of Speech.

In English there are three main positions - of the Subject (1), of the Predicate (2) and of the Object (3).

Three types of pseudo sentences:

1. Woggles ugged diggles. First words are subjects; consequently their property is to

2. Uggs woggled diggs. present objects or things. Second words are predicates;

3. Woggs diggled uggles. they indicate actions. Third words are objects; they

indicate things or objects of an action.

Three test frames to test and explain his classification:

1. The concert was good (always).

2. The clerk remembered the task (suddenly).

3. He went there.

Limited by the frames he defines main positions that are characteristic for English. In each frame he uses the Method of Substitution. He affirms that all the words that can be put in a definite syntactic position present/form a certain positional class of words.

Due to the method of substitution he singled out four positional classes of words and fifteen groups of function words.

BUT the research had led to a certain confusion - the same very word could be included into several classes.

4. Lev Scherba (1880-1944), a Russian (Soviet) linguist,

a head of the Leningrad Phonological School

Explicitly formulated three principles of classification of lexical-grammatical classes

Three principles of classification:

1) Lexical Meaning (lexical meanings of words allow to analyze a common property of a class of words and thus to single out generalized Grammar Meaning, for example, the one of the Noun, of the Adjective, etc.);

2) Morphological Form (each part of speech has a common way of word-building and changing);

3) Syntactic Function (each pert of speech can take an appropriate position in a sentence).

2.3. Classification of parts of speech

The biggest subdivision of parts of speech are the ones of Categorematic words (÷ýðüõýðÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂõ ÃÂûþòð) and Syntacategorematic/syntactic words (ÃÂûÃÂöõñýÃÂõ ÃÂûþòð). The Classification is based on three principles formulated by L.Scherba.

Characteristics of words/parts of speech | |

Categorematic words/parts of speech | Syntacategorematic parts of speech |

1) Language units/elements that have lexical meanings, denotes references (elements of reality). For example: *Table, joy (nouns that denote a thing and a phenomenon); *To bring, to create (verbs that denote actions); *Big, happy (adjectives that denote qualities); *Soon, well (adverbs that denote time and manner) 2) They can take a definite syntactic position and serve the functions of members of a sentence. For example: *The Noun can serve the function of the Subject (first position) or the one of the Object (the position after the Predicate), or the one of the Predicative (a part of the Predicate); *The Verb serves the function of the Predicate (the position after the Subject) or a part of that which is the Complement (a part of the Predicate); *The Adjective - the Attribute (before the Subject or the Object) or the Predicative; *The Pronoun - the Subject or the Attribute; *The Adverb - the Adverbial Modifier (in the beginning of a sentence - before the Subject, between the Subject and the Predicate, inside of the Predicate - between auxiliary and notional verbs or at the end of a sentence), etc. | 1) Language elements that do not have independent Lexical Meaning. For example: *She is waiting for him (does not have an independent Lexical Meaning, though in that position it points at the object). 2) They are not objects of Thinking. For example: Such words as of, since, the, a, and, etc. can not denote definite things, objects, phenomena. 3) They have mainly grammar functions. For example: *A book of mine (shows possession); *A trip to Kiev (direction) 4) They are phonetically weak, are not stressed with intonation. For example: *#1, 2, 3 Their functions are: a) to show definite relations between Categorematic parts of speech For example: *#1, 3 b) to specify Grammar Meaning of the Categorematic parts of speech For example: *A boy and the girls (boy, girl have the Grammar Meaning of the Noun). |

Syntacategorematic words

Refer to the Categorematic words/parts of speech | But under certain conditions loose their lexical content and keep only grammar function |

For example: | |

I have a new book (as a Categorematic word, means to possess). | I have bought a new book (as a Syntacategorematic ne, has only a grammar function - refers to the Present Perfect of the notional verb to bring). |

Some parts of speech do not have morphological signs.

For example:

�

1) Since, before, after can be:

* prepositions: after the revolution;

* conjunctions: I reached the station after the train had left.

* adverbs: You speak first, I will speak after.

2) the Noun can serve different syntactic functions:

*A table lamp (Attribute);

* On the table (Object)

�

There are 13 parts of speech in English:

9 Categorematic: | 4 Syntacategorematic: |

The Noun (denotes objects, things, phenomena): man, world, life, rain, spring, etc. The Verb (expresses actions): to run, to think, to develop, to enjoy, etc. The Adjective (names signs, qualities and characteristics of objects and things): beautiful, ridiculous, magnificent, strange, smart, etc. The Adverb (denotes reason, purpose, circumstances, place, time, manner, etc. of an action): yesterday, soon, quickly, occasionally, etc. The Numeral (shows number or quantity of something): one, 2003, twelve, first, second, etc. The Pronoun (substitutes the noun in accordance to the lexical gender the latter expresses): he, she, anything, all, etc. Words of the category of state and condition (express a definite state of an object; they all play syntactic function of the Predicative in a sentence): afraid, asleep, aware, etc. Modal Words (show different attitudes to reality; express probability of an action): probably, perhaps, eventually, likely, etc. Interjections (present emotional reaction of a speaker): wow! (amazed), oh! (surprised), oops! (puzzled, embarrassed), etc. | Conjunctions (show definite combinations of semantic parts in a sentence): and (addition), but (contrast), or (alternative), because (cause), when (time), etc. (which, that) Prepositions (express different relations between main and dependent words in an expression or in a sentence): a book is on the shelf, to go to Chicago, to marry in spring, to speak about him, to look at people, to meet on Monday, to dream of better future, etc. Particles (help other words to express different semantic shades of their meanings): to be in (to be in a certain place), to be on/off (ex.: lights are turned on/off), to be over (finished, completed), to look at (direction), to look for (to search), to look after (to take care of / to resemble), etc. Articles (are certain determiners of the Noun; can determine the Number, can show if a noun names a certain concrete thing or some abstract phenomenon, etc.): a student should clean the class-board (any/one student; one concrete class-board), __ students are very funny people (all students like a class of people; not some definite students), etc. |

As for their Grammatical Meanings Categorematic parts of speech

are divided into three general groups:

Categorematic parts of speech that name objects, things, phenomena and their signs:

the Noun (1), the Adjective (3), the Verb (2), the Adverb (4), the words of the category of state (7);

Categorematic parts of speech that point to objects, things, phenomena and their qualities or quantity but do not name them (they substitute the former): the Pronoun (6), the Numeral (5);

Categorematic parts of speech that express the attitude of a speaker to what feelings, emotions and wills they are expressing: interjections (9) and modal words (8) which are not parts of a sentence (!).

2.4. Theory of the field structure of the word.

Theory of the Morphological Field:

In a group of words there are ones which have all indications (signs) of a definite morphological part of speech; there are also words which have not all indications (signs) of a definite morphological part of speech. The former form the nucleus of the morphological field of a certain part of speech; the latter - its periphery.

For example:

*The word table form the periphery of the Noun, not the nucleus, because it can, for example, have a sign of the Adjective. In the word-combination a big table it has a sign of the Noun but in the word-combination a table lamp - the one of the Adjective.

*Words like pen, woman, sky, etc. form the nucleus of the Noun. They always are main and attributed in word-combinations.

Two general tasks of linguists are:

to define the structure of the field and the composition of the language elements (words) in the morphological field of a part of speech;

to determine the indications which make some language elements close to another or other morphological parts of speech (ex. with table).

III The Noun

General characteristics of the Noun. Its Grammatical Meaning, syntactic functions and the system of word-formation.

Subcategorization of the Noun.

Grammatical categories of the Noun.

The problem of the Gender of the English Noun.

The category of Number.

The category of the Case.

3.1. General characteristics of the Noun. Its Grammatical Meaning, syntactic functions and the system of word-formation.

Characteristics of the Noun:

The Noun refers to the Categorematic parts of speech:

it has lexical meaning and can take a definite syntactic position and serve some functions of a member of a sentence.

The Noun has its own Grammatical Meaning:

it denotes objects, things, phenomena. All the nouns (does not matter what type of objects, things or phenomena they name, concrete or abstract) function in a language in the same way.

For example, the nouns man (concrete), friendship (abstract) both name, denote not signs or qualities and not actions or circumstances but an object and phenomenon (which can both be included to the group of Things).

The Noun can serve the syntactic functions of the Subject and the Object.

Besides it can also be the Predicative. Though this index makes the Noun and the Adjective alike because they both can serve the syntactic function of the Predicative.

For example, He is a man (a noun). He is smart (an adjective).

The Noun has a strong system of word-formation.

It is very important in the light of Grammar for they not only change the meanings of words but also indicate their belonging to the Noun.

The word-formative suffixes of the Noun are divided into two general groups: those which denote persons and those which denote abstract things.

For example:

*suffixes which denote persons:-er, -ist, -ess, -ee (singer, specialist, actress, employee, etc).

*suffixes which denote abstract things: -ness, -ion, -tion, -ity, -ism, -ment (kindness, obsession, rotation, security, pluralism, development, etc.).

The Noun has a weak system of word-changing (a kept sign of a synthetic language):

its root and stem coincided. Some nouns can have both forms, Singular and Plural.

For example, pen - pens, day - days, star - stars, etc.

Grammatical categories of the Noun are poor.

*There is the Category of the Number (boy - boys, study - studies, etc.).

*The Category of the Case has been still under certain doubts (will be seen later on).

*The Category of the Gender completely disappeared by the end of the Middle Ages though some scientist tend to regard Gender as a grammatical category of the English Noun (will be seen later on).

3.2. Subcategorization of the Noun.

There are two general classifications of the Noun.

The first is based on the principle of three properly correlated kinds of nouns - individual names, generalized names for alike things and names for a group of things. It is schematically presented in the table 3.1.

Table 3.1

The first classification of nouns

Nouns | ||||||

Types | Proper | Common | Collective | |||

Meanings | Names and nicknames of definite people, places, things | Names of any object, thing, phenomenon | Name the sum total, the whole complex of things | |||

Peculiarities | Do not have a generalized conceptual content, meaning | Have a generalized conceptual content, meaning | Present the whole complex as a certain unite | |||

Varieties | _ | Concrete | Abstract | Material | Have the opposition of Singular and Plural Number | Do not have the opposition |

Examples | John (the name of a man), Mr. Fix-it (the nickname of a man), Sevastopol (the name of a town), Crimea (the name of a geographical place, of a peninsular) etc. | table, man, girl, apple, book, etc. | idea, friendship, faith, serendipity, joy, etc | water, oil, sugar, gold, acid, petrol, etc. | family - families, class - classes, people - peoples = folk - folks, society - societies, nation -nations, etc. | people (as a sum total of human beings), humanity, mankind, nature (as the sum total of animals, plants, things in the universe), etc. |

The second classification of the Noun is based on the principle of opposition - individual 'personal' names and names for other things. It is schematically presented in the table 3.2.

Table 3.2

The second classification of nouns

Nouns | |||||

Types | Common | Proper | |||

Meanings | Name any object, thing, phenomenon and have a generalized conceptual content, meaning | Name and nickname definite people, places, things and do not have a generalized conceptual content, meaning | |||

Opposition | Countable (can be counted) | Uncountable (cannot be counted) | _ | ||

Varieties | Concrete | Abstract | Concrete | Abstract | |

Examples | chair (-s), box (-es), vegetable (-s), woman (women), wife (wives), knife (knives), etc. | difficulty (-ies), life (lives), idea (-s), doubt (doubts), spirit (-s), soul (-s), belief (believes) etc. | water, money, bread, meat, salt, butter, vinegar, trousers, scissors, hair, etc. | knowledge, love, hatred, honesty, wealth, wisdom, courage, faith, respect, tolerance, etc. | Dnepr (the name of a river), Barbara (the first name of a woman), Everest (the name of a mountain), London (the name of a city), Africa (the name of a continent), Shakespeare (the second name of a man), the Victory (the name of a ship), etc. |

3.3. Grammatical categories of the Noun.

Grammatical categories of the Noun are poor.

*There is the Category of the Number.

*The Category of the Case has been still under certain doubts.

*The Category of the Gender is considered to have completely disappeared by the end of the Middle Ages, though there is still some arguments as for considering Gender as a grammatical category of the English Noun.

The problem of the Gender of the English Noun.

The gender of an object, thing or phenomenon is expressed with lexical, but not grammatical, means (boy - girl, man - woman, bull - caw; he-goat - she-goat; star - it; window - it, ship - it/she, etc.). Grammatically there is almost no sign to indicate the gender of a noun (the suffix -ess can be considered as an exception: steward - stewardess, actor - actress, etc.).

Some scientists, however, (for example, an American linguist Strand, a Russian linguist Bloch) consider Gender as a category of the English Noun as all the nouns can be substituted by the appropriate pronouns. Though it would not be really correct for the propriety of the Pronoun (to substitute the noun in accordance to the lexical gender the latter expresses) is shifted to the Noun. It can breed a certain confusion in the understanding of the problem of English Grammar.

The category of the Number.

1. The category of the Number is based on the opposition of singularity and plurality.

For example:

parent - parents, tree -trees, man -men, life - lives, etc.

Singular form of the Noun is multiciphered (üýþóþ÷ýðÃÂýþõ; can stay singular or change into plural) and Plural - simple (þôýþ÷ýðÃÂýþõ; cannot change for has already been changed).

The opposition of singularity and plurality can, for example:

express differences in size (ex., wood (like material to be used to make a fire; logs) and woods (like an area of trees, smaller than a forest));

distinguish a class and a subclass (ex., fish (as a creature that lives in water) and fishes (refers to different kinds of fish)).

2. The category of the Number as for the formal indices is presented in two general models - open and closed.

1). As for the open model or productive (it goes on working) it is displayed by the formal index - the suffix -s/-es (in the Plural form of the Noun) or by its absence (in the Singular one).

For example:

Star - stars, floor -floors, knife - knives, etc.

*To the allomorphemes of the suffix -s/-es the following three are included:

[s]; after voiceless (unvoiced, surd, breathed) consonants (ex., cats);

[z] after vowels (ex., indices) and voiced consonants (ex., dogs);

[iz] sibilant (ex., kisses) and hushing sounds (ex., bushes).

2). As for the closed model (it is a certain historical heritage and does not develop) it is grammatically displayed only morphologically or in the sequence with a verb:

morphologically: Ox - oxen, child - children, woman -women, man - men, phenomenon - phenomena, antenna - antennae, data - datum, etc.

in the sequence with a verb: the noun sheep does not change its grammatical form at all: The sheep is here (Singular Number). The sheep are here (Plural Number).

3). There are also nouns which are unchangeable and have only singular or only plural form:

only singular: advice, information, knowledge, furniture, etc.;

only plural: trousers, pants, pyjamas, spectacles, etc.

The category of Case.

The Case

refers to the relations of an object/thing/phenomenon (which is denoted by a noun) to other objects, actions and signs, on the one hand, and

presents the means of material or linguistic expression of these relations, on the other.

The are two opposite points of scientific view as for the existence of the category of Case in English:

1) there is the category of Case in English (there are a few approaches to the problem of the English Case);

2) there is not the category of Case in English (a new point of linguistic view).

1. Five general approaches to the problem of the English Case are based on the principle of the number of the cases.

1). There are two cases. The principle of Form.

Henry Sweet

(19th century; an English linguist; Classical Grammar; principles of morphological form and syntactic function)

On the ground of the principle of Form he distinguished two grammatical forms of the English Case:

the Common Case (shows the relations of an object in the linguistic form of a noun with actions (verbs) and signs (adjectives)).

The notion of the Common Case was introduced to the English Grammar by H.Sweet;

the Possessive Case (shows the object's possession of another object, thing, phenomenon).

In the second half of the 18th c. Robert Laud (an English linguist) attracted the attention of the scientists to a diachronical change in the structure of the language. The change concerned with the old English Genitive Case (ÃÂþôøÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù ÿðôõö) which lost its original grammatical meaning and kept only the meaning of possession.

For example:

Mother (the Common Case) did not know where the son's (the Possessive Case) hat (the Common Case) was left.

2). There are five cases. The principle of Lexical Meaning.

In the field of Semantic Grammar five cases were distinguished on the principle of Lexical Meaning. They were said to be Nominative (øüõýøÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù), Genitive (ÃÂþôøÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù), Dative (ôðÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù), Accusative (òøýøÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù) and Vocative (÷òðÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù) cases.

The approach was criticized by

Jence Otto Harry Jespersen

(1860-1943; a Danish linguist; Philosophy of Grammar; principles of morphological form and syntactic function)

The critics was based on the peculiarity of the approach as it was grounded on Latin which left some traits in English structure but was different: the Latin Noun changed its Grammatical Form whereas the English Noun could change it only in Number and when a possession was emphasized. Latin cases were Nominativus, Genitivus, Dativus, Accusativus, Vocativus and Ablativus (þÃÂôõûøÃÂõûÃÂýÃÂù).

For example:

Table 3.3

Comparing Grammatical Forms of the cases of the Latin and English Noun

Latin | English | ||||

Amicus (friend); the stem is amico-. The noun of the second declension | Friend | ||||

Case | Singularis | Pluralis | Case | Singular | Plural |

Nom. | amicus | amici | Nom. | friend | friends |

Gen. | amici | amicorum | Gen. | friend | friends |

Dat. | amico | amicis | Dat. | friend | friends |

Acc. | amicum | amicos | Acc. | friend | friends |

Voc. | amice | amici | Voc. | friend | friends |

Abl. | amico | amicis |

Critics by O.H.Jespersen.

It is seen from the example that the English Noun does not have a grammatical paradigm of its declension. Consequently, if there is no signs of material expression of changes (Grammatical Form), if there is no opposition or properly correlated relations, then there can not be a proper Grammatical Category as there is no base for it. It is the first drawback. Though O.H.Jespersen considers the Case as a Category of English. Then there is another drawback which is the lack of attention to the relations of possession that has a material expression in the grammatical form of the Possessive Case.

3). There are four cases. The principle of Syntactic Function.

Four cases in the light of the approach are stipulated by the syntactic position of the Noun in the Sentence. The English Noun can take the positions of the Subject, Attribute, Direct Object, Indirect Object. Consequently there are proper cases distinguished. They are presented in the table 3.4.

Table 3.4

Correspondence of the syntactic function and the case of the Noun

Case | Syntactic Function | Example |

Nominative | Subject | A human lives. A table is made of wood. |

Genitive | Attribute | There is a human (human's) approach. There is a table lamp. |

Accusative | Direct Object | He needed a human. He brought a table. |

Dative | Indirect Object | He wrote to a human. I took a book from the table. |

The drawback of the approach.

The Case is a morphological Category. In the approach under critics, firstly, Morphological Form is not taken into consideration at all, secondly, Lexical Meaning is not paid attention at. Thus, the category from the morphological turns out to become syntactic, which brakes the basic principles of Grammar in general.

4). There are as many cases as many prepositions. The principle of analytics.

Theory of Analytical Cases

A case of a noun is stipulated by a peculiarity of the combination of a noun and a preposition.

For example:

To a man - the Dative Case (direction towards sb/sth is emphasized);

By a man - the Instrumental Case (an instrument is emphasized);

In a man - the Locative Case (a place is emphasized).

Critics by O.H.Jespersen.

The combinations under consideration are only prepositional combinations of a noun and preposition and can not be taken as the ground/principle for cases' classification.

5). There are three cases. The principle of Substitution.

In the light of Structural Approach (Structural Grammar) there was the system of three cases distinguished. Each case was grounded by the principle of substitution of a noun by a proper personal pronoun (table 3.5).

Table 3.5

The principle of Substitution in stipulating the three English Cases

Case | Substitution by Personal Pronoun | Example | ||

Using a noun | Substituted by a personal pronoun | |||

Type | Pronoun | |||

Common | Personal | He, she, it | A student is writing a test. | He is writing a test. |

Possessive | Possessive | His, her, its | He looked at mother's car. I like the colour of the car. | He looked at her car. I like its colour. |

Objective | Personal Pronoun in the Objective Case | Him, her | She wrote a letter to a man. | She wrote a letter to him (She wrote him a letter). |

Critics.

The approach is quite a reasonable one as it takes into consideration the Lexical Meaning (a propriety to substitute a noun by a proper personal pronoun), the Syntactic Function (the propriety of a noun to serve a definite syntactic function in a sentence) and the analytical character of the English language (to change grammatical forms by an analytical means, not by synthetic, inflective/inflectional ways).

Though Morphologically the English Noun can hardly change: it has an opposition only in the category of the Number, not in the one of the Case. As for the latter (the Category of Case) materially, morphologically it can have an opposition only when the relations concern some possession. Then there is the opposition of the Common Case and the Possessive one (as in the classification introduced by H.O.Jespersen).

2. Contemporary approach to the Category of Case.

Nowadays there is a tendency to think that there is no morphological category of the case in English.

Firstly, there are no definite morphological forms as material expression of the Case. As a result there is no paradigm of the morphological forms of it.

Secondly, there is a certain confusion as for syntactic functions of the Noun in the form of the Common Case and in the form of the Possessive Case.

Thus, in the both forms the Noun can serve the syntactic function of the Attribute, though, naturally in the Objective Case it should serve the function of the Subject or the one of the Object and in the form of the Possessive Case - the function of the Attribute.

For example:

There is the John's book. The noun in the Possessive Case is an attribute in the sentence.

There is a table lamp. The noun in the Common Case is an attribute (prepositional attribute), too.

Thirdly, the Possessive Case in English has a few definite peculiarities, which makes it different from synthetic ways of word inflection. They are the following.

1). The main Grammatical Meaning of the Possessive Case is to express a certain possession.

For example:

A student's book; a students' book

Though there are also other meanings.

For example:

The day's wait = the wait during a day (the meaning of temporality)

The hair's width = the width of a hair, very narrow (the meaning of measure)

The snake's character = the character that resemble peculiar behaviour of snake (the meaning of quality)

2). The Possessive Case has limited functions:

a) limited lexical function:

usually it is used with names of animated objects

For example:

A girl's prize; a dog's bed, etc

But not table's lamp

b) limited positional function:

a noun takes the place before another noun which is attributed (prepositional location)

For example

A table lamp (not lamp table);

A girl's prize (not a prize girl's);

A dog's bed (not a bed dog's)

3). Singular and Plural forms of the Noun in the Possessive Case differ only in writing, not in oral speech. There are only rare exceptions.

For example:

Boy's [boiz]; boys' [boiz] (sounds the same)

Child - child's; children - children's' (an exception)

4). The index 's is not fixed only for the Noun; it can also be added to a word-combination or a clause.

For example:

The girl's father (added to the word);

The dancing with my friend girl's father (added to a phrase);

The girl I go with's father (added to a clause).

Conclusion:

the contemporary English Noun does not have the Category of the Case. There is a tendency to consider the Case as the syntactic attributive category (the syntactic category of attributivity) the formal index of which is 's.

In the contemporary English Grammar the Possessive case is included also in the grammatical group of Possessives to which nouns in the Possessive Case, possessives without following nouns, the possessive pronouns and phrases with the preposition of are included.

For example:

Mother's car (the noun in the Possessive Case);

She got married at St Joseph's. Alice is at the hairdresser's (the possessive without a following noun).

There is my new coat. That coat is mine (the possessive personal pronoun)

It is easy to loose one's temper when one is criticized (the possessive impersonal pronoun)

That policemen is a friend of Lucy. His work is no business of yours (phrases with the preposition of )

IV The Problem of English Article

4.1. Interpretation of the status of the English Article.

4.2. The problem of the number of articles (how many morphological forms the Article can be presented in).

4.3. Functions and significance of the Article.

Functionally there are two forms of the Article - definite and indefinite. The forms are not changed. Though they have definite phonetic versions/the versions in pronunciation (drawing 4.1):

the | a / an | |||||

Transcription | Position | Example | Transcription | Position | Example | |

[ ] | Before consonants | On the table | [ ] | Before consonants | On a table | |

[ ] | Before vowels | In the apple | [en] | In the stressed position | In an apple | |

[..:] | In the stressed position | I told: 'On the table, but not on a table!' | [ei] | Before vowels | I told: 'On the table, but not on a table!' |

Drawing 4.1. Allomorphemes of the Definite and Indefinite Forms of the English Article

There are three main problems/questions in accordance with the English Article:

1. If the Article is a definite word or not; and what is its relation to the Noun (the problem of garamatical status)?

2. If the Article is a definite word, then if it is a definite part of speech (the problem of morphological status)?

3. What is the number of articles in English (the problem of Grammatical Category)?

4.1. Interpretation of the status of the English Article

There are two general approaches to the grammatical morphological status of the Article (Drawing 4.2).

I. II.

As a word it defines a certain type of the Noun and has its Grammatical Meaning (to define concrete known or any, not particular, noun) | The combination 'an article + a noun' is considered to be an analytical form of the Noun (its material morphological index) |

Drawing 4.2. The problem of Status of the English Article

1. The approach to the Article as to a definite Syntacategorematic word which defines the Noun.

Article here is compared with the Adjectival Pronoun (his, her, its, etc.).

BUT such approach leads to treating the combination 'Article + noun' as an attributive word-combination and, consequently to treating Article as the Attribute in the Sentence, which is not possible for the Article does not possess the Lexical Meaning.

It has its own Grammatical Meaning which is to define concrete known or any, not particular, noun. Its Grammatical Category is based on the opposition of the definite - indefinite attitude to the Noun. Though there is no Lexical Meaning of any type of the Article. Consequently it can not be regarded as a member of a sentence because only Categorematic words/parts of speech (which have their own individual lexical meanings) are considered as members of the Sentence.

For example, compare:

*It is my book.

My is an attribute of a direct object book as it, firstly, defines the noun book and, secondly, has its own lexical meaning, it is lexically-morphologically expressed by the possessive pronoun my in the possessive form of a personal pronoun I which means 'the subject of a verb when the speaker or writer is referring to himself/herself''.

*It is a book. It is the book.

Neither article a nor article the can be considered as the attributes because in spite of having grammatical meanings neither of them has a lexical one (what then the attribute will be expressed by?).

2. The approach to the Article as to a peculiar morpheme of the Noun.

The English linguist Christophersen emphasizes analytical nature of English and considers the Article as a morpheme of the Noun.

Firstly, he distinguishes three Morphological Forms of the Noun in the Category of the Article (table 4.1):

Table 4.1

Three Morphological Forms of the Noun in the Category of the Article

Morphological Form | Grammatical Meaning | Its versions in | |

Singular | Plural | ||

Zero form | attitude to a thing as to a general phenomenon | cake | cakes |

Cake is nice food. | Cakes are liked by kids. | ||

A-form | treating a thing as any representative of a class of things | a cake | __ |

I'd like a cake. | |||

The-form | considering a thing as a unique or concrete known one | the cake | the cakes |

The cake we've eaten was delicious! | The cakes we've eaten were delicious! |

Secondly, Christophersen stipulated his approach with the following arguments:

1) Article resembles the Auxiliary of the Verb as both of them create a definite analytical form of a part of speech, auxiliary verbs - of the Verb, articles - of the Noun. He stipulates Article as the Auxiliary of the Noun on the ground of the following arguments:

article is a formal morphological index of the Noun;

article does not have Lexical Meaning.

BUT these arguments are not enough and there is a confusion:

article is not a pure unique index of the Noun.

For example:

(The) water (noun) was wonderful those days. They water (verb) flowers.

article is a definer of the Noun but it does not create Morphological Forms of it whereas auxiliaries create new Morphological forms of the Verb, they change it. Consequently, there is a syntactic connection of the Article and the Noun and there is not of the Auxiliary and the Verb.

For example:

*Article can be substituted by another proper word/pronoun (syntactic connection):

The man is a smart one. = This man is a smart one.

A girl suddenly came in. = Some girl suddenly came in.

*Auxiliary cannot be replaced/substituted by any other word (morphological connection):

He is singing a beautiful song. We have been climbing the rock for three hours.

In the Occidental science there has still been some arguments to the problem of Article (where to refer it). In the Post-Soviet science the Article is treated as a Syntacategorematic part of speech.

4.2. The problem of the number of articles (how many morphological forms the Article can be presented in)

There are two approaches (traditional Grammar and contemporary approach):

1) there are two articles in English (drawing 4.1): definite and indefinite (the Category of Article is based on the opposition);

2) there are three articles (table 4.1): zero, definite and indefinite (the Category of Article is grounded on the proper correlation of the absence, emphasis on the definite character of the Noun and emphasis on the indefinite character of the Noun). The absence of Article is regarded to be a relevant characteristics as it has the meaning (identifying a thing as a general phenomenon) and two properly correlated characteristics - identifying a definite and indefinite things.

4.3. Functions and significance of the Article

There are three general functions of the Article: morphological, syntactic and semantic.

1). Morphological function of the Article.

Article is the main formal material morphological index of the Noun.

For example:

*Would you sponge the water from the table? (water is the noun: it is defined by the article which is a formal index of the Noun);

*Would you water the flowers? (water is the verb: it follows after the personal pronoun in the function of the Subject (direct word order in English))

2). Syntactic function of the Article.

It is called the function of the index of a group of the Noun's left limit: Article forms a left limit to the following after it group of words that define or attribute the Noun which takes the limit right position. Article defines the Noun but not obligatory is put directly before the Noun.

For example:

A house; A big house; A big stone house; A comfortable big stone house, etc.

3). Semantic function of the Article.

Semantically the Article can express:

a) a certain identification (a concrete or unique thing);

b) a reference to a class of homogeneous or similar things (any of the class).

The Meaning of identification is the main for the Definite Article the.

The can mainly be used:

a) in the repeated nomination of an object:

For example:

A day was terrific! I will never forget the day.

b) with the limiting attribute:

For example:

The man, who entered, was really nice.

c) when it is stipulated by the situation:

For example:

Not a word was spoken in the parlor.

d) to define unique phenomena:

For example:

The sun, the moon, the sky, the earth, etc.

e) to express the meaning of the whole class of things;

For example:

The dog is a domestic animal.

The reference to a class of homogeneous or similar things (any of the class) creates the Grammatical Meaning of the Indefinite Article (a/an).

A/an can mainly be used:

a) to present a definite object which is not distinguished from the class of homogeneous or similar ones; presents a thing as one from a class:

For example:

You can read a book while waiting.

He is going to be a doctor.

b) to express a generalized meaning which is realized in sentences expressing abstract classification:

For example:

A swarm (any) is more beautiful than a goose (any).

V The Verb

5.1. Grammatical Meaning of the Verb

5.2. Word-formative and word-changing systems of the Verb

5.3. Classification of verbs

5.3.1. Morphological

5.3.2. Semantic

5.3.3. Syntactic

5.4. Grammatical Categories of the English Verb

5.1. Grammatical Meaning of the Verb

The Verb refers to the Categorematic parts of speech:

it has lexical meaning and can take a definite syntactic position and serve some functions of a member of a sentence.

The Verb has its own Grammatical Meaning:

it expresses a dynamic sign which elapses in time, so it has the Grammatical Meaning of action:

* activity (e.g., We study and work);

* state (e.g., He feels happy);

* existence, a sign that an object or thing exists (e.g., A chair is a piece of furniture).

It has a propriety to show elapsed time of an action.

5.2. Word-formative and word-changing systems of the Verb

Word-changing system of the Verb is richer in comparison with other parts of speech.

There are two main means of word-changing of the Verb

Synthetic | Analytical | |

Is characteristic to inflective languages For example: Work - works - worked | In English the Verb is the only part of speech which analytical forms For example: Have worked, has been working, is working, etc. |

Drawing 5.1. Two main means of word-changing of the Verb

Word-formative system is rather poor.

There are three main means of word-formation of the Verb

Affixation | Conversion | Reversion | |

(adding an affix to create a verb) | (a change from one part of speech into another) | (returning to a former state by rejecting the suffix of a noun) | |

1. The suffix -en (of the Germanic/Teutonic origin) For example: to redden | For example: Water (the noun) - to water A convict - to convict | For example: Sea-bathing - to sea-bathe Blackmailer - to blackmail | |

2. The suffix -y (of the Roman origin) | |||

For example: to magnify | |||

3. The suffix -ize (of ? origin) | |||

For example: to mobilize |

Drawing 5.2. Three main means of word-formation of the Verb

5.3. Classification of verbs

There are three main classifications of verbs based on the different principles.

5.3.1. Morphological Classification

The classification is based on the Principle of Form (tab. 5.1).

Table 5.1

Scheme of Morphological Classification of Verbs

Verbs | ||

Regular | Irregular | |

Characteristics | The stem of a verb + the suffix -ed | Past tenses and past participle are formed by other means (a word changes in its stem) |

Examples | They invited us for a party. We have studied the problem. You have been asked an important question. | He brought an exquisite book. She has gone to Liverpool We have been taught since our cradle. |

5.3.2. Semantic Classification

There are three main subclassifications that are based on the Principle of Meaning, both Lexical and Grammatical (tab. 5.2).

Table 5.2

Scheme of the 1st Semantic Classification of Verbs

Verbs | |||

Categorematic | Auxiliary | Modal | |

Characteristics | 1. Have Lexical Mean ings 2. Can change their forms synthetically or analytically | 1. Do not have Lexical Meaning. 2. Have Grammatical Meaning to express peculiarities of the elapsed time | 1. Have a propriety to express people's cognitive-emotive attitude to reality. 2. Have pure morphological characteristics: a) are marked with the defective paradigm (hardly change their forms); b) can correlate only with the Infinitive (a verbal) |

Examples | Last time we quickly completed the project. We have already done the work. | Where are you going? Do not be too nervous! I have just come. | He must be going home now. She might have done the work. You should be more attentive. |

*There is a problem, a certain confusion:

1) auxiliary verbs can also be Categorematic in accordance with the function they serve in a sentence, for example:

I have a dog (Categorematic). I have bought a dog (auxiliary).

She does a lot to help him (Categorematic). She does not know how to help him (auxiliary).

To be or not to be? (Categorematic). We are the champions (auxiliary, linking verb). They are studying now (auxiliary);

2) there are also some linking verbs Lexical Meanings of which have completely disappeared, for example:

He grew thin (ÃÂý ÿþàÃÂôõû). She turned pail (ÃÂýð ÿþñûõôýõûð). They grew red (ÃÂýø ÿþúÃÂðÃÂýõûø). We felt cold (üà÷ðüõÃÂ÷ûø).

There are also some linking verbs that has kept their Lexical Meanings, for example:

He felt a cold touch (ÃÂý ÿþÃÂÃÂòÃÂÃÂòþòðû àþûþôýþõ ÿÃÂøúþÃÂýþòõýøõ).

A characteristic feature of Linking Verb is that it can correlate with an adjective (which is treated as the main word).

Table 5.3

Scheme of the 2nd Semantic Classification of Verbs

Verbs | |||

Limited | Unlimited | Dual | |

Characteristics | Characterized with the intention to express a completed action | Express an action as constant duration, subsequent state is unknown | In accordance with contextual circumstances express either one or another meaning (of a completed action or of constant duration) |

Examples | To catch, to fall, to find, to die | To sit, to be, to know, to exist | To laugh, to look, to live To move: He moved away quickly (limited). Nothing moved along the road (unlimited). |

The 3rd version of Semantic Classification includes the following types :

the verbs of feelings and perception which are not used in Continuous (e.g., to feel, to love, to hear, etc.);

the verbs of mental, intellectual, activity (e.g., to think, to cognize, etc.);

the verbs of psychic states which are not used in the Passive Voice (e.g., to understand, to know, to comprehend, etc.);

the verbs of speech (e.g., to speak, to talk, to say, to tell, to proclaim, to declare, etc.);

the verbs of movement and location in the space (e.g., to move, to run, to settle, etc.);

other verbs that can not be classified in this version. They are usually classified in the 1st and 2nd versions (e.g., to find, to have, to complete, etc.).

5.3.3. Syntactic Classification

The classification is based on the Principle of Syntactic Behaviour (tab. 5.3)

Table 5.4

Scheme of Syntactic Classification of Verbs

Verbs | ||

Transitive (intentional) | Intransitive (unintentional) | |

Characteristics | Demand certain completeness which is expressed with the following adjectives or nouns | Can be used in speech autonomously, without any determiners and compliments |

Examples | To become famous, To catch a ball, to find the key | To walk, to sleep, to come, etc. She slept, then walked and finally came. |

5.4. Grammatical Categories of the English Verb

General Characteristics of the Categories of the English Verb

I Categories of the Finite Verbs

The Voice (Active, Passive): expresses relations of an action, its agent and object (an agent does an action (the Active Voice); an action is done over the agent or at the object (the Passive Voice)).

For example:

A carpenter made a table (AV). The table is made of silver (PV)

The Mood (Indicative (expresses a statement), Subjunctive/Conditional (expresses a condition), Imperative (expresses an order)).

For example:

Struggle for study enables you to develop (Indicative Mood). You can develop (IM).

If you had warned him beforehand, he would not had made that stupid mistake (Conditional Mood). May you be happy together (Subjunctive Mood). I wish you were here (SM).

Behave yourself, or else! (Imperative Mood) Don't ask such ridiculous questions! (IM)

The Person (a defective category): expresses the relations of a verb and a concrete Person. The formal index (the suffix -s/-es) has been still kept only to express the relations of a verb and the 3rd Person Singular in the Present Tenses.

For example:

She has been living here for ages (BUT I have beenâ¦). He lives happily (BUT We live happily)

The Number (a defective category): expresses the relations of a verb and the Singular Number of the 3rd Person in the Present Tenses. The formal index is the suffix -s/-es.

For example: look #3

The verb be also changes its forms in accordance with the Number in Present and Past

Tenses.

For example:

He/she is the best driver I've ever met. You/we/they are the best drivers⦠I am the best driverâ¦

He/she/it/I was there last year. You/we/they were there last year.

The Kind/the Aspect: specifies a character of action in the elapsed time (expresses a form of committing an action without being named in the word but completing the Lexical Meaning of it).

There are the Perfective Aspect and the Imperfective Aspect.

Grammatically Limited (Transitive) verbs refer to the Perfective Aspect and Unlimited (Intransitive) verbs - to the Imperfective Aspect.

For example, the following verbs refer to:

a) the Perfective Aspect: to become (famous), to catch (a ball), to find (the key)

b) the Imperfective Aspect: to walk, to sleep, to come, etc. She slept, then walked and finally came.

The Time (Tenses) is the leading category and makes the Aspect/the Kind subordinate. The category of Tense expresses relation of an action to a moment of speech (a point of correlation of the Tense-forms). An action can:

Coincide with the moment of speech (Present Time/Tenses);

Precede the moment of speech (Past Time/Tenses);

Be thought as a planned, arranged, supposed after the moment of speech action (Future Time/Tenses)

The Aspect of Grammar Time. In each kind of Time the verb can take the form of an appropriate Aspect:

Indefinite (usually done). The Aspect can express:

a definite finished action

For example:

I met him yesterday.

a number of actions in a sequence

For example:

She gets up, washes, dresses and drinks her coffee at 8 every morning.

not finished action, the attention is concentrated at the fact that the action happened

For example:

She drank coffee noisily.

Continuous (in longevity/duration at the moment of speech). The Aspect emphasizes the significance of the very process and its temporality, duration.

For example:

She was working when you phoned. She is sleeping now, be quiet. We will be flying to Paris on the fifth of October.

Perfect (completed by the moment of speech);The Aspect expresses the completeness of an action and usually emphasizes the result of it.

For example:

She will have graduated from university by the summer, 2010. Look at her! She has cut her hair short!

Perfect Continuous (having been in certain duration up to the moment of speech).The Aspect express the completeness of unrolling an action and emphasizes its longevity.

For example:

We had been listening to him for ages before he finally stopped. You have been doing odds jobs since the morning.

The collision of Time and Aspect results in Grammatical Tense (12 in number).

II Categories of the Non-Finite Verbs

The Infinitive

The Gerund do not refer to a Person but refer to another verb in a Finite Form

The Participle

VI Non-Finite Forms of the Verb

6.1. Terms that are used when Non-Finite Forms are studied

6.2. The Paradigm of the Non-Finite Forms

6.3. Functions and Significance of the Non-Finite Forms

6.1. Terms that are used when Non-Finite Forms are studied

In the tab. 6.1 different names for the Non-finite Forms of the Verb are presented and certain critics towards the attitudes.

Table 6.1

Terms that are used to name Forms of the Verb that do not make agree with Persons

Names | Assessment | |

in English | in Russian | |

Nominal | øüõýýÃÂõ | Contradicts with the notion of the Verb, its Grammatical Meaning |

Non-Predicative | ýõÿÃÂõôøúðÃÂøòýÃÂõ | Contradiction: even though Non-Finite Forms of the Verb are really non-predicative (cannot serve the syntactic function of the Predicate in a Sentence), they still can be a part of the Predicate, serve the syntactic function of the Complement of the Compound Predicate |

Non-Finite | ÃÂõûøÃÂýÃÂõ ýõÃÂøýøÃÂýÃÂõ òõÃÂñðûøø | Appraisal: a significant relevant propriety of these forms of the Verb is emphasized: the absence of Grammatical Category of Person in them |

Verbals | ||

Verbids |

Non-finite Forms are included to the system of the Verb on the ground of the following characteristics:

They keep the Grammatical Meaning of the Verb.

They all can be formed from any verb; the exception is Modals (which have a defective paradigm and neither change nor produce other forms).

They have the Paradigm of forms of the Time and Aspect/Kind of Time and the Paradigm of the Voice Forms.

The model of their government coincides with the one of the Finite Forms (they are also defined by the Adverb and demand the Complement).

There are different number of Non-Finite Forms distinguished in Classical and Traditional Grammar (drawing 6.1).

Classical Grammar: Principle of Morphological Form and Syntactic Function | Traditional Grammar: Principle of Morphological Form | |||

Infinitive | 4 in number | Infinitive | 3 in number | |

Gerund | -ing-Form: *Participle I (Present Participle); *Gerund | |||

Participle I (Present Participle) | ||||

Participle II (Past Participle) | Participle II (Past Participle) |

Drawing 6.1. Classification of Non-finite Forms

6.2. The Paradigm of the Non-Finite Forms