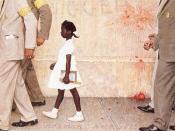

Ruby Bridges "Two, four, six, eight, we don't want to integrate," were the shouting words coming from a mob of racist protesters on Nov. 14, 1960 in New Orleans-the day public schools were integrated. These were just some of the words that 6 year old Ruby Bridges heard as she made her way into her new school, surrounded by US Marshals. At first, she didn't realize that the harsh words were directed towards her, she thought it was Mardi gras. She could not yet conceive how important her bravery was.

Ruby was born in Tylertown, Mississippi in 1954. In 1957, economic conditions forced her family to move to New Orleans where her father worked as a custodian and her mother cleaned floors at a bank. The entire family was actively involved in the church and their neighborhood community. When integration was ordered, the NAACP backed Ruby's assignment to a first grade class at the all white William Frantz Elementary School.

Her intelligence and scores on the school board exam granted her the ability to attend the school.

Ruby's mother Lucille was extremely proud of Ruby for doing so well, and for being chosen to help begin the process of integration in the area. Lucille supported allowing Ruby to attend William Frantz Elementary, to better Ruby's future, along with the future of all black children. Ruby's father Abon, on the other hand, felt that she should stay at her school because she was doing just fine where she was. After some thought, the couple decided that the right decision would be to be strong and have Ruby attend William Frantz.

On her first day of school, guards were stationed at the end of the street that the Bridges family lived on. Deputy US Marshal, Al Butler along with several other US Marshals picked up Ruby and her mother at their home and escorted them to the school. The angry mob was already there, waiting to yell and spit at Ruby, who didn't understand their hatred. She was simply going to school to learn.

Mothers of the children who attended William Frantz Elementary came into the school and took their children out of because of Ruby's presence. Ruby and her mother were told to sit down in the school office, and ended up sitting there all day until the bell rang at the end of the day, when she was told she was dismissed. None of the teachers in the school would teach Ruby, so a teacher was hired to teach only her. This teacher, Barbara Henry was a major influence and aide in little Ruby's life.

Mrs. Henry was originally from Boston. She taught overseas on a military base, then was married and moved to New Orleans with her husband. At the time, she was unaware that she would be teaching Ruby Bridges on the day that she showed up for work. Because of all the protestors and mothers pulling their children out of school, Barbara Henry was told to go home and come back the next day. That, she did, as did Ruby.

The two never missed a day of class the whole year. They formed a close bond and Ruby learned a great deal from her teacher, including reading skills. Mrs. Henry read to Ruby quite often, which she enjoyed very much, and to this day is very thankful for. For the most part, Ruby was taught by Mrs. Henry alone, a class of one. She had to eat lunch alone in her classroom, and for a while wasn't eating her lunches. This was because each morning, one of the protestors outside the school would threaten to poison and kill Ruby. For a while, she would only eat packaged and sealed foods such as a new bag of chips or cookies and Coca Cola.

Also, Ruby began calling her younger brother and sister names and acting out what she had been hearing from the protesters, on her dolls. At this point, Ruby's parents got in touch with psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Coles. Dr. Coles met with Ruby over a period of time at no cost, talking to her and had her draw pictures in order to see how she was coping with her new school and all the protesting. At first Ruby would draw black people with a pink crayon just as she would draw white people. But the black people she drew, such as herself or family, would have body parts missing, or be deformed in some way. Throughout all the heckling and hatred placed upon Ruby, she remained brave and did not give up. Her visits with Dr. Coles, her teacher Barbara Henry, her parents, and her faith in God helped her through this confusing time in her life. She made it through the year, and passed with all A's on her report card.

Every morning Ruby would say a prayer for the people protesting outside of her school. She never reciprocated the anger and hatred that the protestors had for her. Ruby prayed: "Please God, try to forgive those people.

Because even if they say those bad things, they don't know what they're doing.

So you can forgive them, just like You did those folks a long time ago when they said terrible things about You." Eventually, white children came back to William Frantz Elementary School and were taught by a different teacher. Ruby asked if they could come into her classroom, and soon they did. The children were not kind at first because of everything their parents were saying about Ruby. They were simply modeling after their parents. Some soon came to see that Ruby was just another little girl, and she finally had a few friends in school. By now, nobody can deny the heroism of Ruby Bridges, along with the courage of her parents to pursue a better education for their daughter, and pave the way for more children to gain a better education as well. Ruby Bridges' bravery inspired the 1966 painting by Norman Rockwell entitled "The Problem We All Live With." It also inspired the children's book The Ruby Bridges Story by Robert Coles. Now Ruby Bridges Hall, she has raised four children, lectures around the country, wrote a book of her own, Through My Eyes, and heads the Ruby Bridges Foundation, which consults with schools "in the hopes," says Bridges, "of bringing parents back into the schools and taking a more active role in their children's education." In the year 2000, Ruby Bridges Hall was named an honorary US Marshal. Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder bestowed the honor upon her and said, "She exhibits the qualities of a U.S. marshal. She's bold, she's brave, she's filled with courage." "I don't believe I'd have the courage my parents had," Bridges Hall said, recalling walking through the mob of protesters outside the William Frantz Elementary School. She said she didn't realize what the trouble was about in 1960 until a white boy told her his mother had forbidden him to play with her.

"If my mother had told me not to play with an Asian or a Hispanic child, I'd have done the same thing," she said. "We are the ones who pass racism on to our children." Ruby Bridges graduated from an integrated public high school in New Orleans. She still lives there with her husband and four sons, who also attended the city's public schools. Today Bridges-Hall works to bring music, dance, and other cultural arts to schools in New Orleans. Through the Ruby Bridges Foundation; she provides funds to give kids opportunities they might otherwise not have. She began her efforts at her old school, William Frantz Elementary. Eventually she hopes to reach children in every state in the country.