Frederick Winslow Taylor, the acknowledged 'Father' of scientific management was a pre classical contributor. Taylor was the founder of a system that stated the relationship of workers and managers to the realm of new science/technology. Scientific management is the approach emphasing production efficiencies by scientifically searching for the 'one best way' to do each job. Taylor pioneered his signature time and motion studies of work processes through this movement, developed an array of principles to enhance productivity, as well as created a mental revolution between workers and employers. The system includes various wage and bonus incentive plans, an array of techniques for measuring work input and output, and an ideology of authority in organisation. Understandably, this new core and field of management has attracted many critics who claimed that the theory dehumanises and exploit workers. However, Taylor's impact on management cannot be denied. Many current management practices are influenced and guided, either consciously or subconsciously, by these traditional concepts.

It is also impossible to fault the brilliance with which scientific management created a lasting formula to resolve the social problems of industrial organisation and influenced the quality of human life.

The birth place of Frederick Winslow Taylor classical ideas came from his actual work experience in Midvale Steel Company. Early in his career he became interested in improving work efficiency and methods. However, Taylor was continually appalled by workers' inefficiencies, which he called soldiering. Soldiering is deliberately working at less than full capacity (Bartol, K., Martin, D., 2001, p36). Taylor ascertains that work could be analysed scientifically and that it was management's responsibility to provide the specific guidelines for workers performance;. This led to the development of the one best (correct) method of doing each task; the scientific management .

Under Taylor's philosophy of scientific management, the role of management changed significantly from that of the past. His emphasis was on making management a science rather than an individualistic approach based upon rule of thumb (Hough, R.J., White, A.M., (2001), pg 586). He set forth to correct the soldiering situation and create a 'mental revolution' between workers and managers based on 4 principles:

1.scientifically study each part of a task and develop the best method for performing it, which replaces the old rule of thumb method.

2.carefully select and then train, teach and develop the worker (previously, workers chose their own work and trained themselves as best they could.

3.cooperate fully with workers to ensure that all work is done in accordance with the principles of science that has been developed.

4.divide work and responsibility between management and workers; Managers think and plan, workers basically execute orders. (previously, almost all the work and the greater part of responsibility were thrown upon the workers).

By maximising the productive efficiency of workers and employers, scientific management would also create prosperity for the workforce by maximising the earnings of workers and employers. Taylor's ideal factory was a metaphor for a better society and this established him as Father of scientific management.

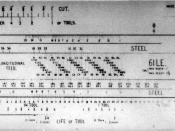

Taylor also emphasised ideas and activities that inspired others to study and develop his methods of scientific management. His most prominent advocates were Frank and Lillian Gilbreths who assisted his development of the time and motion studies. The Gilbreths were best known for their study of work arrangements to eliminate wasteful hand-and-body motions and their design of proper tools and equipment for optimising work performance (Bartol et al., p37). Moreover, Henry L. Gantt was a close associate of Taylor in extending Taylor's incentive wage system. For instance, Gantt devised an incentive system that gave workers a bonus for completing their jobs in less time than the allowed standard and awarded supervisor's bonuses when workers reached this standard.

Scientific management became a "movement" with wide potential applications and many followers. No single figure in the history of industrialization did more to affect the role of the manager than Taylor, and in fact those who came after him had to take Taylor's work into account in the application of their theories and techniques. For instance, he provided many of the ideas for the conceptual framework later adopted by the administrative management theorists, including Fayol's 14 principles of management: clear delineation of authority and responsibility, separation of planning from operations, the development of incentive systems for worker, task specialisation/standardisation etc (Robbins, S., Bergman, R., Stagg, I., Coulter, M., 2000, p47). Many of the principles of scientific management were similar to those ideologies in Max Weber's bureaucratic model (Robbins et al., p48). This was particularly true of Taylor's view that management itself should be governed by rational rules and procedures.

Despite admirable goals and achievements of improved performance, Taylor has attracted numerous critics. Perhaps the best known and major critics were Wrege and Perroni's (1974) investigation of Taylor's account of the pig iron handling experiments at Bethlehem Steel (Hough et al., p586). Wrege and Perroni suggested that Taylor had created a 'pig tale'. In particular, the authors demonstrated discrepancies in Taylor's account of the experiments. However, Taylor's purpose was to make a fundamental change in how work was organised, and used the pig iron experiments as a basis for his examples. Therefore, when evaluating the original intent of contributors, any criticism should be carefully considered in light of its importance to overall understanding (Hough et al., p597).

It is thus of little wonder that Taylor and his advocates were not without opposition because the new approach involved a complete overhauling of traditional managerial practices (Robbins et al., p44). Critics charged that it encourage excessive specialization, degraded work, and encourage personal competition, hostility and a sense of alienation (Bartol et al., p37). Workers also resented time study procedures and standardization of every aspect of the job. They view that workers were being treated like machines and were requested to operate according to mechanistic rather than humanistic principles. This remains the primary criticism today and is therefore one of the biggest limitations of the theory.

In spite of these criticism, the principles of scientific management spread rapidly throughout American industry and in Europe for several decades. Further, when we recognise the time setting in which Taylor and his followers were experimenting and writing about their management views, it is implausible that they could have the same views on industrial humanism that exist today (Robbins et al., p46). Taylor was a product of his environment. He was strongly influenced by the rationalism of economic theory and engineering practices at the time. Within this framework he made major contributions to management thought, contributions which are applied widely throughout industry today. His contributions met the needs of industrial management at a time when traditional ways were fast becoming obsolete (Robbins et al., p46).

The first half of the twentieth century was a period of diversity in management thought. Modern concepts of organisation theory are not completely distinct and unrelated; they evolved from earlier views. These developments have increased our understanding of organisation theory and management practice. In order to truly understand organisation theory as it exists today, one must appreciate the historical context in which theories have been developed and tested. Frederick Taylor's contributions and legacy on management cannot be denied.