SanFelippo � PAGE �10�

Adam SanFelippo

Mr. Kearney

American Hero/4

12 December 2008

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as Journey Through the Afterlife

The afterlife, in unanimity with the underworld, includes a plethora of mythological characters and symbols in the form of the river Styx, Cerberus, Charon, and Hades itself. The journey into the underworld is instigated with a person's death and preparation for passage into hell, as he needs to realize certain requirements. Greek mythology suggests the feral River Styx, "across which the dead were ferried," as the dangerous river leading into the underworld (Webmaster). On the river souls drift along until they meet the requirements, gaining admittance from Charon and Cerberus. The river Styx "literally means 'hateful' and expresses loathing of death" and many Greek philosophers believe the water to be a form of poison (Encarta). "Charon, the ferryman on the river Styx, leads souls across the river on his raft into Hades, admitting passage only to those bodies, "containing a coin" (Encarta).

Charon also forces those souls without the coin to float continuously on the river Styx for one hundred years. "Those who had not received due burial and were unable to pay his fee would be left to wander the earthly side of the Akheron, haunting the upper world as ghosts" (Atsma). In Greek mythology, Cerberus, or "hellhound," a three-headed dog with a dragon like tail, guards the entrance to Hades, admitting souls but letting no one escape. The final attribute of the afterlife, on the side of Hades, includes the description of Hades itself. Hades is the land of the dead which, "is a dim and unhappy place, inhabited by vague forms and shadows" (Encarta). The characteristics of Hades also add to the atmosphere of demise and hopelessness, which surrounds the River Styx. By including the characteristics of the afterlife throughout The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Twain offers supportive details which illustrate the novel as Huck Finn's journey through the afterlife and to the gates of Hades.

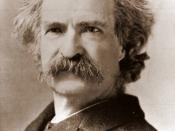

The initial and most important necessity for a novel of the afterlife is the addition of a deceased character. In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain starts the novel by depicting the pessimistic Huckleberry Finn's unhappiness in the present world, describing the afterlife and hell as a superior home: "but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn't stand it no longer, I lit out.â¦I felt so lonesome I most wished I was dead" (Twain 1, 3). After escaping from his home, the unpredictable Huckleberry Finn returns, only providing his polemical father with an opportunity to take him away to his little house, where again Huckleberry Finn finds himself unhappy in his current environment. Finally, Huckleberry decides death to be the cure for all his problems and develops an elaborate scheme to "fake" his own passage into the afterlife: "Well last I pulled out some of my hair, and bloodied the ax good, and stuck it on the backside" (Twain 25). In reality, Huckleberry Finn takes his own life to flee life's parsimonious problems and looks back on the event, as a soul listening to the cannon probing the river for his dead body: "They won't ever hunt the river for anything but my dead carcass" (Twain 26). The events preceding his escape in the canoe to the island develop Huckleberry Finn's death and begin his journey as a spirit through the afterlife. By providing the novel with the first part of the afterlife, Twain begins to build up The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a novel of Huckleberry Finn's death and journey through the afterlife and to the gates of Hades.

The next condition for the sporadic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to symbolize Huckleberry's quest for passage into hell and the afterlife is the addition of the River Styx. In the novel, Twain uses connotative phrases and negative imagery to distinguish the river, as it includes and exhibits many of the characteristics of the harsh River Styx in Hades. Twain begins the explanation of the river to parallel the River Styx when he generates a sense of hopelessness and consternation in Huckleberry Finn and Jim as they float down the river, allowing it to dictate their journey with its "treacherous and capricious" ways (Smith 332). Just after passing St. Louis, Huckleberry Finn and Jim find themselves in the center of a violent and monstrous storm, with no protection as they float submissively down the unforgiving river. Sensing the hazardous situation, Huckleberry Finn and Jim gaze in silence at the surrounding walls of confinement which the domineering river produces: "When the lightning glared out we could see a big straight river ahead, and high rocky bluffs on both sides" (Twain 49). Lightning symbolizes evil and destruction in relationship with an enumerable amount of immoral suggesting phrases. The dangerous and evil connotative links with lightning provide a perfect setting for a portentous predator, the daunting river, to lead its victims astray on a terrorizing journey.

As their journey carries on, Huckleberry Finn and Jim encounter further hazards as the rivers takes them on a path straight into a steamboat, shattering their raft. Twain describes the steamboat with the connotative phrase "black cloud" in order to show it as a juggernaut in Huckleberry Finn's path. The intimidating river brings the minuscule raft and the mammoth steamboat together, forcing Huckleberry Finn and Jim overboard: "She come smashing straight through the raft" (Twain 71). By leading Huckleberry Finn up against such an overwhelming force, the river demonstrates its ultimate objective, to end Huck's quest for freedom and passage into the underworld. Twain's use of the connotative relations with the color black and lightning allows him to build up the river as an infuriating yet it carries him impediment to Huck's journey and effectively depict it to represent the River Styx. The demonstration of the river to be an archetype of the River Styx, further develops the novel as a story of the afterlife.

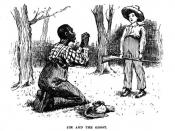

The next device that Mark Twain uses in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to develop the demoralizing nature of the river are the illustrations from the first edition of the book. In the first edition book, Mark Twain, "paid [E.W.] Kemble $1,200 and pushed him hard" to exemplify precise representations of the characters and events in the novel (Webster). One of these illustrations takes into account the ruined steamboat housing dead bodies that Huckleberry Finn and Jim come across. Through the pauses in lightening strikes, Huck spots the wrecked steamboat in the center of the river: "I see that wreck laying there so mournful and lonesome in the middle of the river" (Twain 50). Through the lighting, connotative to death, Huck notices the abandoned and helpless steamboat, which is located in the middle of the relentlessly destructive river. The description of the disfigured steamboat provides yet another event Twain uses to present the river as a disparaging force present in the journey of Huckleberry Finn and Jim. Twain also advises Kemble to incorporate the immobile steamboat in the picture collection of the first edition novel, which generates an even higher elevation and air of destruction as he brilliantly depicts the destruction of the river. The illustrations by E.W. Kemble in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn allow Twain to recollect the current image of the steamboat in his mind, thus allowing him to articulate the full level of destruction present in the corridor of the river. By using such a vibrant image to display the steamboat and the death onboard, Twain further develops the river as not only a destructive force but also an unforgiving one as well. By including the negative images in the illustrations, Twain again effectively characterizes the river in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as the River Styx and the novel as an afterlife story.

As Huck continuous his journey down the river, Twain again uses the vibrant image a illustration creates to aid the maturity of the cunning yet powerful nature of the river and continue its resemblance to the River Styx. When Huckleberry Finn and Jim float down the river, they again happen upon another victim to the river, in the form of a house and a dead man: "here comes a frame house down [the river]. There was something lying on the floor in the far corner that looked like a man--he's dead" (Twain 38). Twain again continues to represent the power and destruction of the river, whether it be the obliteration of a two-story house or a human being. Also, to show the unpitying nature of the river, Twain reveals at the end of the novel the dead body in the corner of the wrecked house to belong to the incompetent Pap Finn as Jim explains to Huckleberry Finn at the end of their journey: "Doan' you' member de house dat was float'n down river kase dat wuz him" (Twain 220). Huckleberry Finn's violent father serves as his irritation and main inspiration to stage his death and free himself from the bondage of life with his father and set out for freedom. By later revealing Huckleberry Finn's grueling journey to escape from his deceased father to be in vain, Twain continues to exemplify the evil and Stygian nature of the river. By using the connotative and explanatory images the pictures produce, Twain completes the parallel of the river in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to the River Styx. By including the essential part of the afterlife, the River Styx, Twain successfully represents the novel as one of the afterlife.

The next obligation The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn needs to fulfill to characterize the novel as one of the afterlife is the addition of the old ferryman, Charon, and the abundant numer of souls he ferries across the River Styx. In the novel Jim befriends Huckleberry Finn and, although a slave, Jim pushes Huckleberry Finn to assist him in his search for money to buy his family: "He was saying how the first thing he would do when he got to a free State he would go to saving up money and when he got enough he would buy his wife. Then they would both work to buy the two children" (Twain 66). Jim encourages and joins Huckleberry Finn's journey to attain freedom, which would lead them and Jim's family to freedom and, in effect, end Huckleberry Finn and Jim's journey on the river. By paralleling the river to the River Styx, the search for liberty symbolizes the pursuit for the coin and the spirit that Huckleberry Finn needs to gain admittance into Hades. The encouragement Jim supplies in the quest for money and independence parallels him to Charon as he accompanies Huckleberry Finn on his journey to Hades on the River Styx and reveals the journey's end when they obtain money and independence. The addition of the quest for coin to gain entrance into Hades again presents the novel as an afterlife story.

The hunt for coin also becomes evident when Huckleberry Finn passes two men on a raft in search of runaway slaves. Huckleberry Finn lies to them about catching smallpox and being contagious, a cover up for his journey, as a spirit, to obtain coin for admittance into Hades. They believe the spirit's story and reluctantly provide him with two coins, one for him and the other, ironically, for the ferryman of Hades himself, Jim: "I'll put a twenty dollar gold piece on this board.â¦Here's a twenty to put on the board for me" (Twain 69). When Huckleberry Finn comes across these men, he acquires the coin he needs for transport with Charon over the River Styx. By including the acquiring of the coin by Huckleberry Finn, Twain provides another circumstance which proves the novel to be an archetype of Huckleberry Finn's journey through the afterlife.

As the spirit of Huckleberry Finn drifts down the river, he also stumbles upon a large quantity of rafts including others in search of coin for passage and some who drift hopelessly along for one hundred years: "A monstrous big lumber raft was about a mile up stream, coming along down, with a lantern in the middle of it" (Twain 27). The raft Huckleberry Finn passes also contains souls in search of the entrance coin, which opens the gates of Hades and permits them to pass. However, other souls remain destined to drift for one hundred years and Jim directly communicates these "lost" souls on the river to spirits: "Once there was a thick fog, and the rafts.â¦Jim said he believed it was spirits" (Twain 89). In the mist on the river Huckleberry Finn and Jim go by yet another raft and Charon, Jim, is familiar with the sounds of the spirits who also float along the River Styx. As Charon, Jim only escorts one spirit on the journey down the River Styx, Huckleberry Finn, and because of it, they pass others who wait for Jim to guide them on their journey. With the addition of Charon and the other spirits, whether they acquire the coin or drift for one hundred years, Twain fulfills the necessity of including Hades' ferryman to further provide support for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a archetype of the afterlife.

The main instance of passage into the underworld only to those who possess a coin transpires with the departed Peter Wilks. Huckleberry Finn, the duke, and the king head ashore and pose as the brothers of the late Peter Wilks and their servant. Becoming aware of the chance, as spirits, to acquire the coin they need to enter the afterlife, the duke and king devise a plan to seize the inheritance: "bein' brothers to a rich dead man, and representatives of furrin heirs that's got left, is the line of work for you and me" (Twain 125). The duke and king soon discover the inheritance of three thousand gold pieces now belongs to the brothers, which would be them through their impersonations. By snatching the inheritance, the king and duke appear to secure their passage into the underworld, thus ending their journey through the afterlife on the River Styx. Huckleberry Finn fights with his conscience in revealing the true identity of the king and duke, ruining their plan to pose as the brothers or rightful inheritors. He then decides to steal the gold and in the end stores it in the coffin of Peter Wilks, giving him the coin he needs for passage into the afterlife: "the only place I see to hide the bag was in the coffin" (Twain 135). The next morning the town lays Peter Wilks to rest along with the money. The money permits his final burial and tranquil passage with Charon to the gates of Hades by providing him with his coin. By laying Peter Wilks to rest only after the coin is in place to provide his passage, Twain realizes the last affair of a spirit being laid to rest and journeying on into Hades, providing additional strength in viewing The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as an archetype of the afterlife.

The last condition for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to be a illustration of the afterlife is Cerberus, the hellhound and guardian dog of Hades. "Cerberus is said to be offspring of two monsters, Typhon (fire breathing serpent) and Echidna (commonly portrayed as an odd and unsettling juxtaposition of beautiful women and deadly serpents") "(Mythical Realm)." Many events occur in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which entail relations between the companionable Huckleberry Finn and dogs. Each time Huckleberry Finn comes across a dog or group of dogs, they go after him, snarling and howling, almost as if they are trying to warn him of hazard such as, for example, the belligerent Grangerford home: "A lot of dogs jumped out and went howling and barking at me" (Twain 72). The dogs stop the pacifistic Huckleberry Finn from entering the land or house, potentially saving him from a Grangerford's mistaking him as a quarrelsome Shepherdson and shooting him. The dogs are paralleled to Cerberus protecting the gates of Hades, refusing entrance to those lacking the coin, which Huckleberry Finn needs in the form of independence. By including the indication to dogs in the novel, Twain effectively represents Cerberus as he stands guard at the gates of Hades. The addition of Cerberus effectively expands the novel as the story of Huckleberry Finn's journey through the afterlife and to Hades.

As the novel continues, the overconfident Huckleberry Finn seals his fate and eventual passage into Hades by vocally professing his destination at the end of his journey through the afterlife. Before arriving at Aunt Sally's quarters, Huckleberry Finn finally identifies his journey through the afterlife and its principle, supporting the novel as an afterlife story with one important reference: "I'll go to hell" (Twain 162). By confessing his final destination and wish to go to Hades, Huckleberry Finn seals his own fate and the conclusion of his afterlife. Only after proclaiming his final destination as Hades, Cerberus, in the appearance of Aunt Sally's dogs, appears at the gates of her home, which represents civilization, the "Hell" in Huckleberry Finn's life. As Huckleberry Finn passes onto the grounds of Aunt Sally's dwelling, dogs quickly surround him as he makes his way towards the house: "a circle of fifteen of them packed together around me, with their necks and noses stretched up towards me" (Twain 166). At first, Cerberus rejects Huckleberry Finn's entrance into Hades, failing to sense his success in his quest to find freedom, the symbol of the coin he needs to enter. Only after recognizing Huckleberry Finn's attainment of freedom, the coin, and voicing the final purpose of his afterlife, Aunt Sally's dogs, the Stygian Cerberus admits him into civilization, and Hell: "half of them come back, wagging their tails around me and making friends with me" (Twain 166). Upon passage into Aunt Sally's home and liberty, Aunt Polly later arrives, taking Huckleberry Finn home into civilization, or as he describes civilization in the opening, "the bad place, and Iâ¦wished I was there" (Twain 2). Huckleberry Finn concludes his voyage through the afterlife and ultimately gains entrance to the place he wanted to be from the beginning, Hell. By including a parallel to Cerberus, the last factor in the afterlife, Mark Twain effectively concludes and provides support to label The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as an archetype of Huckleberry Finn's journey through the afterlife and successful entrance into Hades.

The combination of the overt river, Jim, the dogs, and Huckleberry Finn's death generates the setting of the novel. In the novel, each piece of the setting implements and depicts a part or peculiarity of the afterlife. By depicting the elements of nature to exhibit character traits Greek philosophers believed to exist in underworld side of the afterlife, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn stands as an ideal example of the archetypal novel of the after life. This is a prime novel that should be used when it comes to a symbolic study. There is a countless amount of symbolism in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck's journey as a journey to the afterlife is just one of the more significant ones.

Works Cited

Atsma. "KHARON." CHARON: Greek daemon, ferryman of the dead; mythology; pictures: KHARON. 2000-2008. Theoi Project. 5 Dec. 2008 <http://www.theoi.co m/khthonios/kharon.html>.

"Hades." Encarta Encyclopedia: Microsoft. 2nd Ed. 1998.

"Mythical Realm". "Cerberus." Cerberus: Mythical Creature of Legend and Folklore, Myth Beast, Mythology Legends. 1998-2008. Mythical Realm. 8 Dec. 2008 <http://www.mythicalrealm.com/creatures/cerberus.html>.

Smith, Henry Nash. "T.S. Eliot" New York: w.w. Norton and Company Publishing, 1977.

Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1994.

Webmaster, comp. "HADES." Latin 1 - Mythology - The Underworld - Hades. 2008. KET. 7 Dec. 2008 <http://www.dl.ket.org/latin1/mythology/1deities/underworld/hades.htm>.

Webster, Samuel. Mark Twain, Business Man. Boston: Little Brown Publishing, 1946.