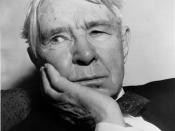

"Chicago," written Carl Sandburg is a rousing piece of writing about the lives of people in Chicago and about the city as a whole. In 1894, Carl Sandburg's father, a laborer in the railroad yards of a small Illinois prairie town, secured a pass for his son to see Chicago. The enormous vitality of the city, as well as its economic injustices, left a deep impression on the young man that would emerge later in his groundbreaking poem "Chicago." As the son of a Swedish immigrant laborer, who in his youth had hitched rides on the rails in search of adventure and blue-collar work, Sandburg was to forge a poetry aimed at the working class, creating a masculine, energetic style that would be read by factory workers over their open lunch boxes. His poetic resources were broad -- he collected folk songs that he would play on his guitar, folk wisdom, and racy slang from working-class neighborhoods and blues lyrics as he developed an ear for the speech rhythms of the populace.

Drawing from his working class roots, he built a raw-boned poetry that violated the poetic norms of the time -- he cast off inherited poetic diction and form and adopted an exuberant free verse. When "Chicago" appeared in 1914, its savage energy created an uproar as Sandburg captured the staggering vitality of the great Midwest City in a poem of nearly mythic dimensions. As opposed to other poets of his generation, Sandburg did not like to experiment with complicated syntax and images, but rather preferred to give the reader something concrete and direct. Therefore, this leaves the tone of the poem to be more serious. Sandburg writes "Chicago" in blank verse in addition to free verse. Sandburg uses anaphora in his poem in lines 6-8. "They tell me you are wicked, and I believed them... I have seen the marks of wanton hunger." He repeats the phrase "They tell me you are," this shows to the reader about how much bad stuff is being spoken about the city. Another literary device that Sandburg uses in "Chicago" is the apostrophe. He uses this when he addresses the city as a person. ("They tell me you are...") Using this technique gives the reader the feeling that the city is somewhat alive and is human. Speaking of which, Sandburg also uses personification throughout the poem, giving the city human attributes. For example, look at lines 18-23. "Under the smoke...Freight-handler to the Nation." Similes are present in line 13 when Sandburg discusses about the animosity of the city. "Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action, cunning as a savage pitted against the wilderness." In addition, this literary tool is used in lines 19 and 20 when Sandburg describes how it is laughing in comparison to a young man and an ignorant fighter, respectively. Another device used in "Chicago" is repetition, in line 18 and 19. Its use here is to show all the afflictions that covered it.

In celebrating slaughterhouses, Sandburg's famous opening lines establish the violent energy of Chicago -- the city's creative force is by necessity also destructive: "Hog Butcher for the World, / Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, / Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler; / Stormy, husky, brawling." In the remarkable rise of Chicago into a bustling hub of commerce, the railroad played a supreme role, linking eastern markets to western grazing lands, while industry became a magnet for immigrant laborers, creating a great mix of foreign tongues and an atmosphere of strife and competition. To survive in working class Chicago was tough. The quick-changing nature of capitalism often worsened conditions with economic injustices: "On the faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger." Thus Sandburg may treat the city initially as having fallen from the path of righteousness, a den of iniquities with its starving citizens and its "painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys" (for the hotel and railroad districts inevitably brought the big-city vices of prostitution and crime).

However, while recording the city's moral degradation, the poet turns quickly to visions of masculine glory, as the city's strength is symbolized by the muscular male body grunting and sweating in physical labor. "Show me another city," Sandburg writes, "with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning." Though Sandburg previously recognizes the people's and cities' failures, he also cheers the invincibility of their souls. At a crucial point the poem breaks out in a celebration of pure activity, as Sandburg identifies the nature of his own poetry, demolishing tradition as it does, with the wrecking crews and the hard-hats: "Shoveling, / Wrecking, / Planning, / Building, breaking, rebuilding."

Yet, that vision does not lose its terrifying aspects. The violence portrayed in the opening lines remains in the "terrible burden of destiny" that causes the defiant, brawling laughter of the ignorant prizefighter drunk with his own power. This is Sandburg's vision of Chicago, a defiant, almost mythological entity that offers both deliverance and pain to humankind. It is a vision presented in a fiercely-toned poem, a tone which matches the city's animal fury and rabid hunger for progress, for Sandburg's Chicago is "Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action, cunning as a savage pitted against the wilderness."