OutlineI.A time in the history of ChristianityII.The battle fought in the name of baptism by the swordIII.The hero in RolandIV.The conquest in an attempt to spread the word of GodV.The essence of the war in the world todayThe Song of RolandThe celebrated epic of the French literature and a superb feature of the literary masterpieces of the Middle Ages, The Song of Roland, otherwise known as La chanson de Roland is one of the first samples of the song of deeds, a hugely famous genre in Europe in the medieval years and those that came after (Zdravko Batzarov). In its commemoration of noble exploits and feudal chivalric example, the epic uncovers quite a lot about the civilization from which it is a part, is priceless to historians in its portrayal of the development of Christianity and morality, and is treasured for its literary quality and excellence. The original and anonymously written version of the epic is long gone.

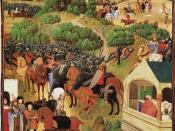

The closest and considered to be best representation of it is the 4000 - line manuscript kept at Oxford, which is deemed to be a reproduction of the original (Nelson). The epic was told in the Anglo - Norman language, it unifies legend and love with chronicled records in narrating the story of Roland and his death, when Charlemagne and the rest of the troops are heading home from a 7 - year combat in Spain (Nelson). It is deemed that the tale was intended to inspire men who are headed for battle. In the same stance as the Iliad, the epic is celebrated for its portrayal of deference and valor as it continues to inspire its readers for every turn of its leaf.

The Song of Roland may not be a reliable historical tool but it utilizes history to its advantage. The tale narrated in the epic could possibly be associated to an event in history particularly the unsuccessful invasion of Spain by the Emperor Charlemagne in the year 778; however such association is quite loose.

Most of the tale is undoubtedly just that; a simple tale with no references what so ever to the events of the past. The epic may not be a reliable historical narrative, but it is a story which employs of kinds of freedom, producing emotional personalities out of dusty characters, generating enemies into the most loathsome of all villains, and breathing on all the like an air of greatness. While it does not afford its readers any facts, any brief connection presents that it negates the account or past event in countless places, but rather legend.

Certain facts seem to imply that The Song of Roland was written more or less at the start of the 12th century, hundreds of years following the reign of the Emperor. It appears enlivened by the essence spirit of the crusades, a period wherein the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages, that time enjoying the peak of its power, chose to spread Christianity into the Holy Land.

The epic, written at that same time, provides the Crusades as an influential part of propaganda. One ought to keep in mind that an opinionated as well as ideological purpose has nothing to do with a verse's structure as a poem.

Despite the fact that no one ever contemplated on taking part in a Crusade until hundreds of years past the demise of Charlemagne, his image as a man of the Most High, beatified and yet in other churches revered as a saint, he was believed to have been in constant communication with the heavenly host as well as the immediate instrument of the Most High's command on earth, and as ardent as a soldier as any has given his persona image an exceptional mark for Crusade's spirit.

The pieces of the past that can secure for itself a place into the epic are reshaped to suit the crusader's vision view of the world. The slaughter massacre at Roncesvalles turns out to be a lot greater than an accident; it turns out to be another tale of good versus evil, an expression of the sin of deceiving the cause of Christianity.

Although in Einhard's account, the Frankish forces are waylaid by the Gascons, a set of Christians who are not in favor of the kingdom empire of Charles, in the epic, the soldiers are waylaid by the Saracens, which refers to the Arabs, and, by mean of addition extension, to the rest of the Muslims. Thus, it aids the crusaders of the 12th century to even more effortlessly view the plight of the Franks in the epic as related to their own.

The epic converts Roland into a hero, an ideal of knighthood for the Crusades of the new generation. He perceives the combat in opposition to Islam as an issue of dutiful responsibility. He is definitely the epic's most stunning male protagonist. The picture of Roland's demise is one of the most dominant and unforgettable incident in French prose and his soul is accompanied to paradise by the heavenly host.

Charlemagne's battle in Spain turns into a pattern of their own battle in the Middle East. Roland, together with Turpin as well as Oliver turns out to be their own celebrated ancestors, representing the model of the sacred fighter, who serves the Most High and his ruler with the same ardent fidelity. The depiction of the Saracens, in contrast, signifies the deliberate wickedness of the Muslims, the opponent they will encounter and wrestle with in the Middle East.

It is in the name of duty, and not for the love of battle that Charlemagne takes up the struggle in opposition to Islam. Along these lines, it is still in the name of duty that Roland fought at Roncesvalles until he breathed his last. It is still in abidance to this call of duty that Charlemagne took revenge for the death of his soldier. In The Song of Roland, duty is usually associated to the subject of love. The bonds of Charlemagne and his soldier, or between Roland and his flock, are stained with deep - seated deference and love. Duty develops unexpectedly from such love, or must, just as absolute duty results unsurprisingly from the transcendent love of the Most High.

Time as well as ingenuity has its means of altering misfortunes. Days of battle and surrender has provided humanity, if literature is to be referenced, praise and its supreme champions.

There can be no tragedy much bigger than those that are sung in narratives and heroic verses. There can be no misery much bigger than those of kings and homelands for their heroes defeated in combats grueling to endure.

Although, more than a few centuries has passed since The Song of Roland was written, the brutal French medieval tale is still one of the most exceptional. True to epic fashion, there can be no misery far more legendary than that of the Emperor Charlemagne, when Roland, his most favored soldier and nephew died in combat. To date, there is no primeval tale that resounds more deeply for the present time and no analysis more essential to comprehend them, than this epic of holy battle, righteousness, and faith.

Epic verses are accounts of nations, its inhabitants, heroes, and most especially, grandeur. For what the days gone past fittingly accounts, humanity redrafts. The year was 778 A.D., during summertime on the margin of France and neighboring Spain, Charlemagne, in an act to expand his territory, lay siege to the Muslim, held Saragossa in custody for more than a month prior to failure and eventually headed home. What has transpired while treading the way home, while the army extended down the tapered valley of the Pyrenees, are likely to be lauded for many years in The Song of Roland, brigands waylaid the luggage string, employed the company of the rearguard in combat, required them down the foot of the valley, and slain them down to the last man standing, and ran away.

Roland and the rest of the rearguard soldiers have died. However, not quite a story of failure, the epic is a remarkable tale of deceit, surrender, revenge, and faith. A martyr that he is, Roland's heroic deed was magnificently portrayed.

He breathed his last struggling along with the greatest arms of France, 20,000 brave souls, the Twelve Peer, his best friend, Oliver, but just past succeeding the field. Not a soul killed him. He blew the horn to withdraw the soldiers in advance, that the Emperor might avenge their losses, with great effort until his temple famously exploded.

In the epic, the misfortune of August 15 is altered. The rearguard was victorious in death, that their success is ordained by the Most High. Roland and the rest of his faithful vassals passed on, but their courageous souls were saved. Roland passed on in a battle he knew must at all times be struggled against.

Without a doubt, it has not. The Middle Ages, as well as all of its ambiguity, fatality, battle, faith, medicine, witchcraft, marvel, knowledge, and, peculiarity is a stream back to the issues that haunts the present times. Beneath the dazzling facade of modernity flow tides hundred of years deep, and occasionally, in times like these, it is as if a current many years turning has trapped and pitched humanity down under.

There is more to the epic than a tale of the death of Roland. It is a tale of a battle involving two great lands of faith which is completely too modern. Following the loss of his best heroes, Roland included, Charlemagne ought to recover the power to conquer the Anti - God in a crucial combat with the fate of humanity at stake.

France was handed over, ambushed, wrecked, led to the edge of damage, but they did struggle against all of those hell. Ganelon, the traitor, abides by implemented rules of vengeance to finish Roland, and eventually, almost ruining everything.

Not withstanding his fatalities, Charlemagne bears the day in combat in opposition to the Emir, Saragossa has been defeated, Roland is finally led to his final resting place, and Ganelon has been brought to trial, was drawn, and was finally quartered. His kinsmen were hung, all thirty of them. Charlemagne is believed to lie still in his grave, his sword left on a gird, and his helm tied up, if ever France once grows in need of his service.

The Song of Roland exalts a battle some are still waging. Nevertheless, the themes it speaks about are like those of the present time, the works of betrayal, revenge, misery, trust, and morality, and the problem of impartiality. If a lesson may be learned from the present day Roland, it is that the terrible reality is of greater worth than the idealized visions of days gone by.

When a hero would want to be immortalized, only the generation yet to come can oblige. And yet again, humanity is standing on the brink, may a sad song not be sung in their remembrance.

Works CitedAnonymous, and Dorothy L. Sayers. The Song of Roland. New York: Penguin Classics, 1957.

Crosland, Jessie. "The Song of Roland." 1999. In parenthesis Publications. 20 June 2008 .

"La Chanson de Roland (1090)." n.d. Zdravko Batzarov. 26 June 2008 .

Lawall, Sarah, ed. The Norton Anthology of Western Literature. 8th ed. Vol. 1. New York:Norton.

Nelson, Lynn Harry. "The Song of Roland." 2008. The University of Kansas. 26 June 2008 .